The Lusitania : Part 7 : Passengers of Distinction

Charles T. Jeffery, of Kenosha, Wisconsin, is better known as an interim figure in an automotive corporation whose legacy spanned 1897-1987, than he is for being a Lusitania survivor.

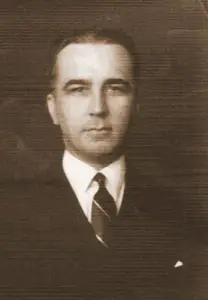

C.T. Jeffery

Charles was the son of Thomas Jeffery, an English immigrant who founded the Rambler Bicycle Manufacturing Company in 1878. The Rambler was the second largest selling bicycle in the U.S. for a time. Thomas Jeffery began assembling the Rambler automobile in 1897, and by 1904 his automobile company was only surpassed in production by Oldsmobile.

Thomas Jeffery died in 1910 and, soon after, Charles T. Jeffery assumed control of the company. Under C.T. Jeffery, Rambler became a public corporation. The Rambler name was discontinued In 1913, and the new, larger, 1914 model was renamed the Jeffery. The car was not a failure, but it did not enjoy the success that its predecessor had.

The afternoon of May 7th found Jeffery in the Lusitania’s smoking room:

When the explosion came, I was in the smoking room of the vessel. It was severe, abrupt, and it seemed as if the ship was raised a little. Directly, she began to list to starboard. All the passengers rushed out on deck. Efforts made to get off the boats on that side were not altogether successful. I saw one boat throw its occupants into the water. We must have been under way at that time, for I saw a woman who had fallen out of the boat struggling in the water.

The crew handled the passengers admirably up to the last. Although most of the passengers went to the starboard side, where the boats were being lowered, I chose the after bridge for, as the ship was sinking by the head, I concluded that this would be the last place above water. And so it was. I didn’t want to jump, for up to this time there was no debris upon the water to which one could hang for support. But a great many passengers did jump at first. The only person who sat at my table who was saved was a young woman from Liverpool. I saw her jump sixty feet from the deck with all her heavy clothes on.

When the ship went down it sank with incredible swiftness. I could not believe that so large a vessel could sink so quickly. I was drawn under probably ten to twenty feet. I have an idea that I did not go any farther down than twenty feet because I think the ship’s bow had reached the bottom at that time. I sank twice, but I had the chance, in the mean time, to get my lungs full of air. It was on going down the second time that I gave up hope. There was not a sign of a boat on the horizon. Persons struggling in the water covered a vast area.

CT Jeffery

On coming up for the second time, I floated around for a while. Then I found an empty can, which gave me some added buoyancy. As I held to this slight support, two men clinging to a cask drifted near me. Later, an old gentleman who looked to be about 75 and a boy of 17 hanging to a plank came slowly towards us.

We kept looking, always, for signs of a ship on the horizon. Once we saw the smoke of a tramp steamer off to the south. None of us would admit that she was not coming our way, yet we all knew that we could not count upon receiving aid from that quarter. Presently we drifted near a partially submerged collapsible boat. It had been stove in, but it was better than the support we had. It took the combined efforts of all five of us to reach it in about twenty minutes ‘though it was only a short distance away.

Our party, supplemented by three men and one woman who had drifted near us, made a load for the boat that kept us in water up to our chests. Thus we floated, while minutes that seemed like hours passed. Finally, a trawler picked us up at 6:10 p.m. Then the trawler cruised around in the vicinity for half an hour, looking for other survivors, but found none. I noticed that most of the people in the water wearing life belts were leaning back in the water, floating without any effort made for possible aid.

My first thought when aboard the trawler was to get warm, so I sat directly over the cylinders. We had no bodies of dead on board, but there was one boy about fifteen who had a broken leg, which was set by a doctor on the trawler before we arrived in Queenstown. Not one of the men I knew on the Lusitania was saved. I particularly regret the loss of a young man of the name of Silver, [Thomas Silva- authors] who was from Texas, and to whom I had become much attached.

Just as the ship was listing and women and children were being put into the boats, I saw a decidedly cool young man of about twenty calmly taking photographs along the deck with a pocket camera. I don’t know whether this young man was saved or not.

A second account by Jeffery gives more details about the time he spent adrift on the collapsible:

At first there had been cries and shouts. Everyone expected that help would come within a few minutes. “When will help arrive?” I heard women floating on their backs calling. Then the cries ceased. People floating on the water’s surface seemed to grow fewer and fewer. How long this lasted, I can’t tell.

The weight of people was making our boat sink lower and lower. One man we rescued weighted, it seemed to us, 25 hundredweight. An enormous, paunchy man, he almost swamped us. We were now up to our waists in water.

1915 proved to be the last year of the Jeffery automobile. In 1916, C.T. Jeffery sold his company to Charles Nash, who expanded operations under his own name. By the mid-1920s, Nash was one of the premiere automobile manufacturers in the United States.

Nash was one of the few independent manufacturers to survive the depression; offering beautiful, streamlined cars in the medium price range that bristled with features unavailable on competing luxury market cars. Nash returned in fine form, post World War II, but styling that grew progressively odder, and crippling competition from Ford and General Motors, doomed the large Nash models. Salvation came when Nash revived Thomas Jeffery’s Rambler. The Rambler was America’s first successful compact car. It offered good fuel economy, and featured quirky styling that many people found cute and appealing in the era of chromed, finned, behemoths. The Nash automobile was discontinued after 1957, but Rambler survived; remaining in production through 1970. The corporation formed by the 1954 merger of Nash and Hudson, American Motors, endured until 1987.

Mr. Jeffery died at age 59, on November 10, 1935, in Philadelphia, PA.