The Lusitania : Part 7 : Passengers of Distinction

Stories of some notable Lusitania passengers.

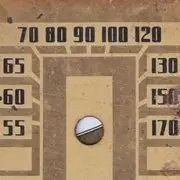

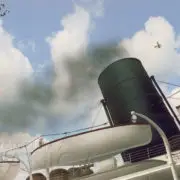

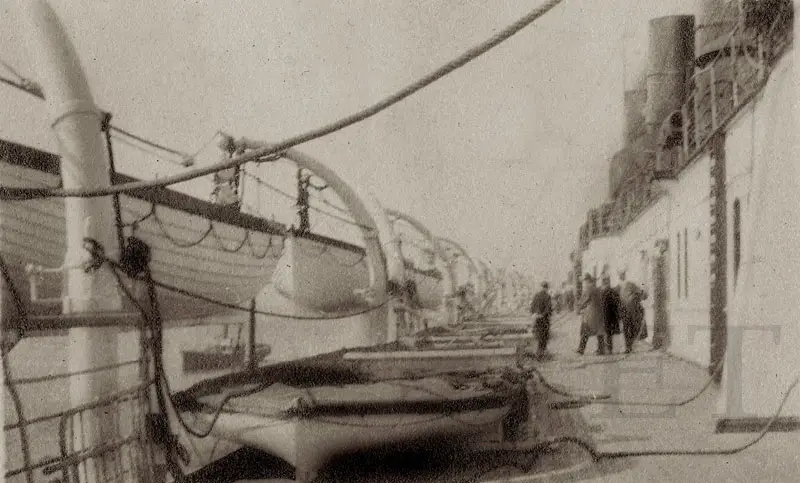

Photograph taken 24th April 1915 showing final configuration of the boat deck

Douglas Hertz, Lusitania survivor, may well have led the most colorful post-disaster lives of any of the passengers. Newspaper columnists loved to profile the likeable bon vivant, and Mr. Hertz was apparently not shy about supplying them with fresh copy.

Hertz was born in England in 1893. He would later tell reporters that he ran away to sea as a youth, and made two voyages, one as a cabin boy on a ship bound for Africa, and one as an oiler. He then settled down in a respectable position as a correspondence clerk at his father’s wholesale chemist and druggist business in London.

Douglas saved his money and, he would later tell reporters, traveled to the United States in 1910 seeking adventure. He aspired to Broadway success, but instead found himself as part of a touring group. He studied for the bar while living in St. Louis, Missouri, and after passing his exams in 1913, spent a year as a practicing attorney.

Hertz would claim that patriotism, and a desire to avenge the deaths of two of his brothers in the war, placed him aboard the Lusitania’s fatal voyage. He traveled in second class.

The moment that the explosion occurred, I got up from my seat and made for the deck. I had hardly taken a dozen steps when the second torpedo struck us with such force that I was knocked off my feet.

I made my way on deck as speedily as possible, and there I found everyone doing what they could to get the women and children into the boats, but unfortunately it soon became apparent that few if any of the ship’s boats could be successfully launched, as the vessel was listing so badly to starboard that the port boats hung right in over the decks and the starboard boats were swung out so far that it was nigh impossible to get into them.

I grabbed a half dozen belts from the first cabin I entered and returned to the deck to give them to women and children. Altogether I must have made six or seven trips below, bringing up lifebelts, before I realized how fast the boat had been sinking, but the last time I came up I had lifebelts in my hands and found nobody aboard to give them to. Then it dawned on me that I had but a few seconds in which to get clear, and for some reason that I have never been able to explain, I forgot to put a belt on myself but dropped all six on the deck and jumped overboard and set out to swim away from the ship.

I knew that she might sink at any moment and swam for dear life for the first minute or two without looking back. Then I turned on my back and witnessed the most tragic sight of my existence. The great vessel had gradually sunk by the bow until she was completely submerged to the fourth funnel, and she was now turning over, her starboard rail now being under water. Then, without warning, she lurched, hesitated a moment, turned over and was swallowed by the Atlantic.

I turned away from the terrible sight, and swam to the nearest piece of wreckage, climbed upon it, and sat there for eight hours until I was picked up by the patrol boat, Julia, of Queenstown.

Douglas Hertz was atop the same overturned lifeboat as Cyril Wallace and Belle Naish. Mrs. Naish sat beside Mr. Hertz, and would later testify that he signed his name to her shoe so that she would not forget it.

Douglas Hertz enlisted, and was granted a commission as second lieutenant in the South Lancashire regiment. He recounted that he saw action in the Dardenelles, and spent time training recruits. Suffering from “nerve paralysis,” he resigned from service at some point in 1916.

Details regarding the next portion of Hertz’s story are hazy, but during the summer of 1916, he returned to the United States aboard the New York, bringing with him his wife, Mollie, and infant daughter, Mary Madeleine. He also brought with him a motion picture, Fighting For Verdun, that he had produced.

Hertz passed his next few months promoting his film. A small article in the New York Times features Captain Douglas Grant Hertz informing an audience before on screening that he had personally seen the German submarine Bremen captured and brought to port in Wales prior to his departure for the United States. Reviews of Hertz’s film reveal it to have been a documentary, the principal flaw of which was a lack of either fighting footage or Verdun footage. Fatal omissions in a film titled Fighting For Verdun. The review in Variety quoted an audience member as telling Captain Hertz that she really enjoyed the orchestration that accompanied the screening.

Hertz then did film work at the various NYC area studios, appearing (unbilled) opposite Marguerite Clark, Pauline Frederick and Elsie Ferguson. He worked at Liberty Bond drives, as well. 1918 found him serving as a machinist’s helper at the Morse Dry Dock and Repair Company, in Brooklyn, NY. His Lusitania experiences, and autobiography up until that time, appeared in the company’s in house magazine, Dry Dock Dial, in October 1918.

Douglas Grant Hertz entered the United States in 1921, aboard the ship Panhandle State. He listed his occupation as publisher. The purpose for his trip to England has not been determined.

To capture the flavor of the rest of Hertz’s life, a newspaper column from 1940 serves best:

If you should happen to encounter on your wanderings in New York, a man nearing sixty who has a polo mallet in one hand and the world tied to the other, his name will be Douglas G. Hertz, possibly the most bizarre human being among all the millions who call this water-girt island their home. Bizarre is scarcely the word. His record treads like something thought up by Achmed Abdullah. Listen:

Served as a Captain in the British Army…was on the Lusitania when it was torpedoed…saw action in Gallipoli campaign…managed the negro heavyweight champion Jack Johnson…dropped a fortune trying to organize a Pan-American oil cartel…acted in silent movies opposite Marguerite Clark…has raced turtles in Miami and pigs in Los Angeles… introduced dog racing to Staten Island…recently completed a deal with Turkish Army for 20,000 donkeys…tried to buy the famous Tombs Prison and turn it into a wax museum…drinks only champagne for breakfast…dines chiefly on fowl…is president of a music publishing firm and owns a swing band… is now producing a Latin American film on Long Island…is a real estate operator…owns the Pegasus Polo and hunt Club at Rockleigh, New Jersey… club has sanctuary for famous old mares and stallions which have made names for themselves in theatrical work… one of these was Anna, a mare who carried the late Valentino through The Sheik…Anna died there recently and was interred with honors. Anna was also famous as an opera star…owns a nightclub named after the horse Sun Beau….great love is polo…says he will bring the son of the late Will Rogers and his polo team east soon to compete at Pegasus….dreams of a vast chain of polo fields from coast to coast “So polo can become the average man’s pleasure rather than the rich man’s fun.”

Mr. Hertz has recently been dubbed “Barnum on Horseback” by his press agents. They like to refer to him as “A cosmopolite Paul Bunyon” which no doubt he is. Certainly at 60 he defies analysis. He says he sleeps only three or four hours out of twenty-four, and consumes strong spirits at a rate of two quarts daily. His arena at Pegasus is said to be the largest indoor arena for rodeo and polo on earth. Actually, it is a vast airplane hanger which Mr. Hertz transferred to Rockleigh from Floyd Bennett Field. “My losses” he admits casually, “are about ten grand a month, but then what’s ten grand when you’re having fun?”

This statement perhaps explains him better than anything anyone else could say.

There are several such articles about Hertz’s alleged frivolity, that span the final thirty years of his life. What is not contained in any of the copious press coverage, is exactly how Mr. Hertz made the jump from shipyard worker to beloved member of the New York area polo set as quickly as he did.

There are many serious articles about the man as well. He owned, for a time, the now-all-but-forgotten New York Yankees football team. He and a partner made a killing when they purchased the unwanted collection of U.S. Patent Office models, some dating back to the eighteenth century, and began direct marketing them thru the Gimbel’s Department Store in New York City. Among the first items made public was a patent applied for by Abraham Lincoln in 1849. Hertz quickly sold the model collection to a group of investors for $75,000.00, who were left holding the bag when interest in the curiosities dried up and sales collapsed. He offered NYC $850,000.00 for the slated-for-demolition Tombs prison, which he hoped to turn into a “museum of crime” in time to cash in on the 1939 World’s Fair: the offer was rejected.

Mr. Hertz was married at least six times. He mentioned, in 1915, that he had a wife and child in St. Louis. This could be Mollie, and Mary Madeleine, who returned from England with him in August 1916, although Mary is listed as being an infant on the voyage manifest. He later spoke of a wife who died in a train wreck. He entered the United States aboard the Aquitania, in 1938, with a wife named Modette, of Fort Cobb, Oklahoma. His immigration records from that voyage state that he became a U.S. citizen in 1937.

Douglas Hertz died in Novato, California, on November 28, 1967. His obituaries recalled him as a fun loving individualist who enjoyed polo and spinning a good story.

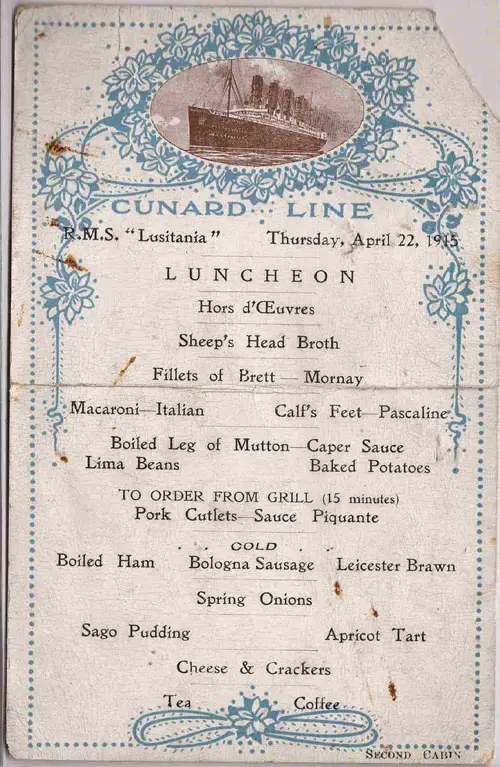

A menu from the Lusitania, April 1915