The Lusitania : Part 7 : Passengers of Distinction

Rita Jolivet, stage and screen actress, remains one of the most frequently referenced of the Lusitania passengers. Unlike many others survivors, she apparently assimilated the memory the disaster quite well. She spoke frequently of the sinking, but she did not seem haunted by it, and the nightmares, panic attacks, guilt and anger which plagued the later years of so many of the Lusitania’s survivors do not seem to have been a major factor in her life. Her fame as a survivor has outlasted the acclaim of her dramatic career.

Rita Jolivet, stage and screen actress, remains one of the most frequently referenced of the Lusitania passengers. Unlike many others survivors, she apparently assimilated the memory the disaster quite well. She spoke frequently of the sinking, but she did not seem haunted by it, and the nightmares, panic attacks, guilt and anger which plagued the later years of so many of the Lusitania’s survivors do not seem to have been a major factor in her life. Her fame as a survivor has outlasted the acclaim of her dramatic career.

Rita Jolivet had her first success on the London stage, but was best known in 1915 for her long run Broadway in the hit, Kismet ,and her critical success in A Thousand Years Ago. Her first major motion picture, The Unafraid, by Cecil B. de Mille, had just opened when Rita boarded the Lusitania that May. The film has survived, and shows that Miss Jolivet’s vibrancy onstage made the jump to the big screen. She seems perfectly at home before the camera, and her acting style is subtler than is often found in films of that era.

Miss Jolivet, according to her family and contemporary reviews, was a born raconteur. Vivacious, expressive, and quite flamboyant, the Lusitania disaster lectures she gave in conjunction with her Lusitania movie, Lest We Forget, were given high marks as both entertainment and education. Rita’s 1918 testimony at the United States Limitation of Liability hearing remains the best, and least fanciful account of her experiences on May 7, 1915. It is presented here in its original Q&A form:

Q. When did you make up your mind to sail; when did you go on the ship?

A. At 8 o'clock in the morning I made up my mind to sail, and I arrived at the dock at five minutes to ten. She was due to sail at 10 o'clock. The reason for my doing so was because the Lusitania was supposed to go quickly, and I wanted to see my brother before he left for the front.

Q. Had you expected, or thought of going on the St. Paul that same day?

A. Miss Ellen Terry had suggested my going, and I said no, that I was in a hurry and was on schedule time and was afraid of not seeing my brother.

Q. When did the steamer finally sail, as far as you recollect?

A. She finally sailed about 1 o'clock.

|

| Rita circa 1910. |

|

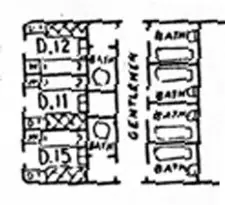

| Jolivet Cabin (D-15) (Courtesy of Paul Latimer) |

Q. Your stateroom was on what deck?

A. On Deck D; it was a very bad room, because it was the last moment, and I had to take an inside cabin.

Q. Were you alone?

A. Yes, but to my great surprise I found my brother in law was going back too. I met him on the boat. He had also decided to hurry back to his wife, and she was in England.

Q. There was no special circumstance on the voyage up to the day of the torpedoing?

A. Not at all, except for rumors.

Q. On that day, on the 7th of May, Friday, did you notice anything about the speed of the vessel, as compared with her former speed?

A. Yes, I noticed that she had slowed down.

Q. On Friday do you recollect seeing the shore at all, and if so, about what time?

A. I saw the shore when I was in the water.

Q. Did you see it while you were on the steamer at all?

A. No sir, because I had not slept well the night before and I had just got up for luncheon, and as I had an inside cabin I could not see the shore from my cabin

Q. Where were you at the time the torpedo struck the ship?

A. I was down in my cabin on deck D.

Q. Did you feel one shock or two shocks?

A. I felt a great shock, and I was thrown about a great deal, and she listed tremendously.

Q How soon did she begin to list after the shock?

A. It seemed almost immediately; I didn't think we were torpedoed, I thought we had struck a loose mine.

Q. What did you do after you felt the shock?

A. I looked out and saw a woman putting on a lifebelt, so with great difficulty I climbed up and got hold of my lifebelt which I carried in my hand.

Q. Where did you get it?

A. From the top of the wardrobe; I climbed up on my bunk and got hold of the lifebelt. I believe there was a second one there, but I couldn't reach it very well. Then I climbed up on deck; I wanted to meet my brother in law who was waiting for me on deck A.

Q. You have spoken of the list that came immediately. Was that before or after you left your cabin?

A. Before I left my cabin; with great difficulty I walked through the corridor and walked up the four flights of stairs to deck A.

Q. You found whom there?

A. I found my brother-in-law and Mr. Charles Frohman, and a Mr. Scott. I believe there was another gentleman behind, that they said was Mr. Vanderbilt, but I don't know; I am not sure of that.

Rita Jolivet

Jim Kalafus Collection

Q. Did you put on your lifebelt then?

A. No; my brother-in-law said “Did you bring any others?” and I said “No,” because I couldn't reach the other. In fact, I didn't know that there were other lifebelts in my room; there were, but I didn't know at the time, in the hurry I just grabbed the first one. Then Mr. Scott went downstairs to deck B and he got up four lifebelts, and gave one to my brother-in-law, and one to Mr. Frohman, and one he kept for himself. And while he was helping Mr. Frohman on with his, and my brother-in-law was helping me with mine, someone stole his, Scott's, lifebelt, and Mr. Scott went down a second time and brought up other lifebelts from deck B, and he gave his away to an old woman. We all offered him ours, and he said no, he could swim better than any of us, and if we had to die we had to die; why worry?

Q. Did you see any of the lifeboats lowered while you were up on deck A?

A. Yes. We agreed to stick together and I looked out on the deck and I saw a lifeboat being lowered, but the guard slipped; it was not lowered evenly, and the women and children were thrown out.

Q. Do you remember which side of the ship that lifeboat was on?

A. I am not quite positive; I am not quite positive but I think it was on the side that was nearer the port, nearer the shore.

Q. That would be the port side?

A. Yes, that would be the port side.

Q. Did you notice anything about the list of the vessel as you stood up on deck A, whether it listed the same or whether it increased or not?

A. No, it did not remain the same. She righted herself. She seemed to right herself. It was only noticeable at the beginning.

Q. How did you finally get off the ship?

A. My brother-in-law took hold of my hand, and I took hold of Mr. Frohman, and we went out through the door on to the deck, and the water swept me away from my brother-in-law and from Mr. Frohman, swept me with such force that my buttoned boots were swept off my feet. I was struck under the water. I sank down twice. When I got up again there was an upturned boat on which I put my hand and clung to…the boat I clung to had canvas on it, and as a great many other people were clinging on to it we were sinking, and then came from under it a collapsible boat that carried away the extra people. We remained out there for three hours and a half, and were picked up by a Welsh collier.

Q. Was this lifeboat you clung to a regular lifeboat or a collapsible boat?

A. It was a regular lifeboat.

Q. When you went over the side was the water up to the deck?

A. It was the water that swept me away.

Q. Water came on the boat deck?

A. Yes.

Q. That part of the ship was down practically at the water's edge?

A. Oh, it had already sunk; it was the water coming up, you see.

Q. The lee side was under water then?

A. Yes.

Q. On what part of the deck were you?

A. I was in the middle of the deck.

Q. In the middle from side-to-side?

A. In the center near the elevator; near the lift.

Q. From side to side?

A. Yes; then we went out on to the deck and saw the ship was sinking right away, and waited ‘til the last moment, you see, and then she sank…

Rita, while in Queenstown, was in the company of Amy Pearl, who was pregnant and who had who lost two of her four children; Maud Thompson, widowed by the disaster; and the injured Lady Marguerite Allan, who lost both of the daughters accompanying her on the voyage. It is likely that Miss Jolivet was also in the presence of survivor Beatrice Witherbee, who lost her mother and son in the disaster, although she is not mentioned in any of Rita;’s accounts. Rita remained in touch with Amy Pearl for time, and Amy’s daughter recalled that the two often visited one another. She may also have kept in contact with Lady Marguerite Allan, for she married Sir Montague Allan’s cousin, James Bryce Allan, in the 1920s. A private film of the wedding was made and has survived, unlike most of Rita’s commercial output.

|

|

|

George Ley Vernon, Jolivet’s brother in law and another victim

|

Rita, circa 1918

|

The Lusitania survivor with whom Rita kept in most constant contact was Beatrice Witherbee. Her husband had placed Mrs. Witherbee in a nursing facility, after she sank into a deep depression. When Rita Jolivet learned of this, she had Beatrice removed from the facility, and brought to the Jolivet family mansion in Kew, England.

Marriage of Rita Jolivet to James Bryce Allen

(Mary Jolivet / Mike Poirier collection)

Beatrice Witherbee married Alfred Jolivet, Rita’s brother, in 1919. The Jolivet family matriarch, Pauline Vaillant, raised both of her daughters to be “great ladies” in the French tradition: artistic, well read, temperamental, and demonstrative. The Jolivet family remembers, with amusement, that Rita’s brother became the polar opposite of his sisters, and was the intelligent but reserved “perfect English gentleman” who occasionally found their flamboyance irritating.

Beatrice and Alfred Witherbee Jr.

Courtesy Lawrence Jolivet

Rita had made her stage debut in London while still a teenager. She was later guarded about the details, and did not care to name the play in interviews. She described it as “a discouraging disaster.’’ But, by 1915, West End, Broadway, and film success had been achieved, and when she boarded the Lusitania, her future prospects seemed unlimited.

She married Count Giuseppe de Cippico in 1916, while at the height of her film career. The pairing of Hollywood and nobility was irresistible to movie magazines, and the couple garnered much press space. Rita made films in the United States, France, and Italy, generally to excellent reviews. Yet, as a 1935 profile in the New York Daily News stated, the career momentum that seemed to be propelling her towards superstardom before the disaster, afterwards faltered, and in the end it can be said that she remained well known, but never made the jump into stage or screen legend.

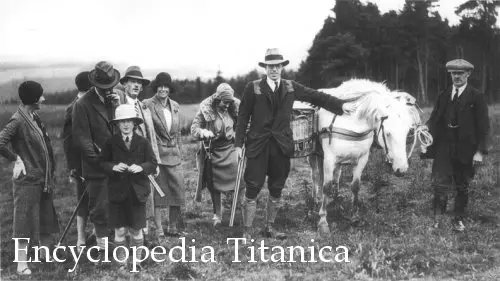

Scotland, early 1930s

Left to right: Trixie Witherbee Jolivet, Lawrence Jolivet, Alfred Jolivet, Lady Jose Bebb,

Count Henri Gaillard, Gladys Lee, Rita Bryce-Allan, Jimmy Bryce-Allan.

(Lawrence Jolivet)

Rita’s career as a performer tapered off by the mid 1920s, and thereafter, she concentrated on her work as a critic with the Paris edition of The New York Herald, her social obligations, and her travels. Her marriage to Count de Cippico ended early in the decade, but her charm, vivacity, beauty, and creativity with dates soon won her the hand of James Bryce Allan. Rita’s gentle deception was an open secret and James Bryce Allan would never discover that Rita was quite a bit older than she had claimed to be. The pairing of the reserved Scotsman and the flamboyant English-raised French actress proved to be successful and lasted until his death. They lived a rarified existence, with a castle in Scotland, an apartment on Central Park West in New York City, a yacht (the Scotia), and a retreat in Nice.

|

|

| Beatrice Witherbee (right: in San Remo). Courtesy Lawrence Jolivet |

|

Rita and Beatrice Witherbee Jolivet’s friendship became strained over the years, due in part to their greatly differing personality types. Rita’s habit of introducing her brother Alfred, nearly a decade younger than herself, as “my older brother” with its implication of “….and his older wife” annoyed Beatrice and her husband a great deal. Lawrence Jolivet, Rita’s nephew, recalled his aunt’s annual Christmas gathering, and charity show, in Edinburgh, as being a family obligation that his parents more endured than enjoyed. Rita’s diary, in turn, contains a reference to “that horrible Witherbee woman….a divorcee!” Lawrence Jolivet told Mike that, at one point, the relationship between Rita and Beatrice deteriorated to the extent that Pauline Jolivet stepped in and forced a truce.

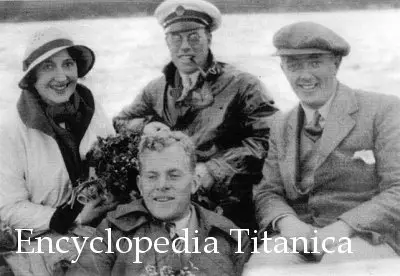

Rita Jolivet and her husband, James Bryce-Allan aboard their yacht, the Scotia in the mid 1930s.

The captain, who is the gentleman on the right side of the frame, ironically bore the last name Turner.

(Courtesy Lawrence Jolivet)

Lawrence Jolivet and his wife visited with Rita, in Nice, during the 1960s. He described her as being “moon faced and happy.” A letter from Rita, written during this era, survives in the Ward Morehouse collection, at the Billy Rose Theatre Library in NYC. Mr. Morehouse had written to Rita enquiring about her Lusitania experiences and asking if the Frohman quote was true; she wrote back, confirming the quote as true and giving an outline of what befell her on May 7, 1915. She stated, emphatically, that the stories later published about the submarine surfacing amidst the debris field were true; she had seen it herself.

Beatrice Witherbee in 1917

Rita died in surgery on March 2, 1971 after being injured in a fall while dancing. She was demonstrating that she could still dance a jig, when she stumbled and broke her hip. Beatrice Jolivet, upon learning the details of her sister- in- law’s fatal accident remarked, “Oh well, she would go like that.” True to form, Rita’s last words were a lie about her age; “I’m only 77,” although she was actually in her 80s. One of her final films, a surreal French comedy by the title of Phi-Phi (1926) surfaced during the 1990s, and was screened in Europe in 2003 to critical acclaim that doubtlessly would have pleased her.

LEST WE FORGET Rita Jolivet’s magnum opus, her contribution to the “blockbuster” film cycle of 1916-1918, and her most lamented lost film, was the epic semi-autobiographic Lusitania thriller, Lest We Forget.

Rita, and her husband, Count de Cippico, formed Rita Jolivet Productions in 1917 for the sole purpose of bringing Rita’s war experiences to the screen. Six months, $250,000.00 of Jolivet family money, more than one thousand extras, and the combined forces of the United States Navy and War Department were combined to what contemporary critics called spectacular results.

The plot, as determined from various 1918 reviews, was extremely broad, and only marginally related to Rita Jolivet’s actual life. She plays Rita Heriot, famed French opera star, who is loved by an American millionaire and lusted after by a lecherous German diplomat. She works as a volunteer telegraph operator. Captured by the Germans, she is to be shot Edith Cavell style, and refuses to be blindfolded. An Alsatian guard, forced into German service, rescues her when an exploding shell provides a momentary distraction, and she escapes to Holland. The Germans will not admit to this embarrassment and Harry, her American fiancé believes her to be dead and joins the French Army to avenge her.

Rita travels to New York after being told, by the German diplomat who lusts after her and who has pursued her to Holland, that Harry has been killed in action. She becomes the theatrical toast of New York, but when she announces that she plans on returning to London aboard the Lusitania, Baron von Bergen, the German lecher who continues to follow her, warns her not to board the ship. She and Charles Frohman sail anyway. Von Bergen wires information to the submarine. The Lusitania is torpedoed. Great panic reigns, but Charles Frohman remains calm. He remarks, “Why fear death? It is the most beautiful adventure in life.” The ship sinks, hundreds are seen struggling for their lives. The lost liner is shown resting on the sea floor. Frohman is lost, but Rita Heriot survives.

Harry, who is not dead, learns of Rita’s survival but misunderstands and thinks that she is a German supporter. Von Bergen plans to rape and then kill the lovely Rita, to cover up his role in the Lusitania affair. He fails, for not only does she protect her virtue, but she also proves her heroism and patriotism to Harry when she strangles the German diplomat with her own bed sheet. To erase the horrible memories, she devotes herself to war service, and in a hospital, she discovers that Harry is alive and wounded. They are happily reunited at the end.

Rita and Giuseppe forged a vehicle in which every conceivable German atrocity was lavishly re-created. Villages were destroyed. A cathedral was shown being ransacked and then demolished. A German high command banquet, somewhat resembling a melding of Henry VIII and Caligula, and celebrating the destruction of the ship utilized scores of extras and was heavily publicized. A sequence showing a Zeppelin raid on London drew much public comment. Rita herself stood in for Edith Cavell, but survived. The U.S. Army supplied Rita with 300 soldiers, playing “themselves” for authenticity in a battle scene shot in Yonkers, NY. One assumes that a like number of non-military extras were enlisted to play The Huns.

The centerpiece of the film was the extended Lusitania interlude. Rita Jolivet Productions was given “rarely granted permission” by the War Department and the U.S. Navy, to use one of the impounded German liners in New York harbor as a floating prop. These agencies took the step of endorsing both the script, and Miss Jolivet, as “outstanding examples of patriotic ideals.” Rita and Giuseppe commissioned a model of the Lusitania, said by them to have cost $50,000.00, for motion sequences as well as the sinking footage. The German liner, Martha Washington, was used for deck shots, the loading and lowering of the lifeboats, the on-deck panic footage, and the final words of Frohman. The sinking culminated with a shot of hundreds of people struggling amid debris after the ship sank. An overhead platform and over one hundred swimming extras were employed for that one image.

Reviewers praised the “horrid realism” of the sinking sequences, and the most highly praised “haunting” visual effect of the whole film was a tank shot of Rita’s 40 foot long Lusitania model at rest on the sea bed, which was cut to after the mass drowning footage. A 1917 article said, emphatically, that 150 paid extras were used in the water scenes, shot in the Hudson River. The film’s press material claimed 450.

Lest We Forget opened at the Lyric Theatre, on Broadway in New York City, in January 1918. Reviews ranged from favorable to ecstatic. Even the city’s Communist paper, The Call, no supporter of war films, praising it for its relentless emphasis on the horrors of war and its refusal to sugarcoat. Rita Jolivet Productions and Metro Films, which Rita had chosen as her distributor, soon published a small booklet of the film’s rave reviews to distribute to theater owners and critics across the U.S. and Canada.

A few reviewers qualified their raves by saying that although Miss Jolivet was engaging and the Lusitania sequences breathtaking, the bulk of the film was simply too lavish, too frenetic, and too packed with plot contrivances surrounding German atrocities to be 100% satisfying. A blurb from the film’s press book captures much of the spirit of Rita Jolivet Productions’ advertising campaign:

Oh ye of little faith, of faltering courage, who question America’s reasons for waging war against the Huns! Find here the answer to your doubts in this dramatic story of Rita Jolivet, fair daughter of France to whom that well-beloved American, Charles Frohman spoke his last immortal words: “Why fear death? Death is the most beautiful adventure in life!” Lest we forget ~ The Sinking of the Lusitania ~The Rape of Belgium ~The Night Attacks on London ~The Wreck of the Cathedral at Rheims ~ The Upheaval of Russian Democracy WILL AMERICA BE NEXT?

Rita Jolivet, as owner/producer of the film, set out to promote it with characteristic vigor. She appeared in person at all of the major openings, and a surprising number of minor ones. She spoke “plaintively” about her experiences on the ship and “forcefully” about the need for vigilance and patriotism, while carrying her Lusitania life belt and the pistol she had with her on board. The critics were unanimous in praising how “energetic” and “delightful” the “piquant French beauty” was as a speaker, even when the film drew mixed reviews. Count de Cippico announced that he would personally carry prints of Lest We Forget to Europe and distribute them to front line soldiers who were normally isolated from films.

Lest We Forget opened at first run theatres during most of 1918, and worked its way down through the theatrical feeding chain throughout 1919, with its final, brief, reviews appearing in 1920.

It would be wonderful to have the opportunity to see a hugely expensive recreation of the Lusitania disaster starring one of its best-known survivors. The plot seems overwrought and more potboiler than serious entertainment: A title card, displaying dialogue between Harry, the hero, and Von Bergen, the villain, read Yes, she is made to love. But, why marry her? Yet, judging by her surviving performances, Rita Jolivet was capable of contained, subtle, screen acting, and even the least favorable reviews of Lest We Forget stressed that she was compelling in the role and that the film was worth watching if only for her talent.

Critics sated by ‘spectaculars’ released in the wake of Cleopatra and A Daughter of the Gods struggled for adjectives adequate enough to describe the film’s visual and visceral impact. It must be noted that the less enthusiastic reviews all came at the end of the film’s first run, late 1918, when critics and the public were weary of the German Atrocity film cycle that had dominated theaters the previous summer.

An early Pop Culture column in the magazine, Motion Picture World, would explore each month’s ten most frequently asked movie questions, posed by audiences. “Each letter, we realize, represents the thoughts of an additional 600 film goers.” One of the March 1918 questions, asked by several hundred readers, was, “Was Rita Jolivet really on that boat?” The answer: “Yes, Rita Jolivet was really on that boat-and she’s awful pretty, too.”

The film has now been missing for 88 years, but with recent discoveries of several other lost Rita Jolivet movies, hope remains that it might emerge from some obscure archive or private collection and allow a new generation of film fans the chance to experience “The Greatest War Film of All Time.”