The Lusitania : Part 7 : Passengers of Distinction

William Uno Meriheina, profiled earlier, was a race car driver who had parlayed his career into a job as a General Motors Export employee.

Edwin Twinning, 19, of New York had worked as a mechanic specializing in race cars and, in that capacity, frequently traveled. He sailed in third class aboard the Lusitania, and vanished without a trace; his body was not recovered and no one who knew him on board left an account mentioning him.

Anne Shymer, 36, of New York City, was the president of the United States Chemical Company. She was aboard the Lusitania en route to London, where she was to be presented to King George and Queen Mary at the Court of St. James.

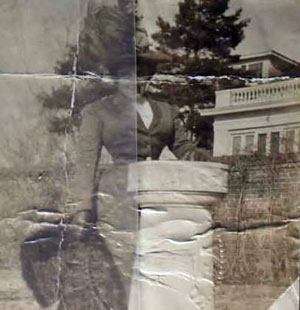

Anne Shymer photographed by her family aboard the Lusitania. May 1, 1915

Mrs. Shymer was born in Logan’s Port, Indiana on May 30,1879. Her mother, Grace, made sure that Anne and her younger sister, Maibelle, were well educated, and she encouraged Anne’s interest in chemistry. Anne studied at Cornell University, and she likely transferred to, and graduated from, another institution for Cornell does not have her recorded as a graduate. She was married to a man named Paterson for a short time and lived abroad until he died.

Anne returned to the United States and continued her experiments in a private laboratory in New York. She remarried on January 16, 1911, to Robert Shimer. They lived together as man and wife for a period of four weeks and then separated. He took off for parts unknown, and she anglicized her last name to Shymer.

Anne was a successful chemist, and formed the United States Chemical Company. She discovered formulas for textile bleach, and invented a germicide intended for hospital use. Anne presented her discoveries to King George’s physician in early 1915. She dined with Premier Asquith, and his wife, during her London visit. Anne returned to New York to make final preparations to expand her company’s business in London. The chemist joked with friends and family that she was to be presented to the King and Queen, “Scientifically if not, socially.”

Anne had returned to the United States aboard the Lusitania, and chose to sail back aboard her as well, because it had been such a pleasant crossing. She carried her formulas with her. Her family came down to the pier to see her off, and photographed her aboard the Lusitania, standing on the B-deck promenade, near her cabin, B-98. She had not been able to locate her husband, and commence their divorce proceedings, before she sailed.

Her actions aboard the Lusitania are unknown; however, when the ship was struck, she may have gone to her cabin to retrieve her jewelry. Her body was among the first recovered, and was numbered 66. The jewelry found on her remains was estimated to be worth $3,900. It was handed over to Mr. Thompson, a Vice-Consul at the American Consulate, Queenstown, but was lost in transit between Cork and the American Embassy in London.

Anne Shymer

Anne Shymer’s remains were sent home on the steamer Philadelphia. Grace Justice-Hankins and her daughter, Maibelle Heikes Justice, filed claims against Germany for lost property, and for the formulas that Anne was bringing to London. Robert Shimer learned of his wife’s death and filed a claim for $50,000. Grace Justice-Hankins passed away in 1924, before a judgment was made. Commissioner Edwin Parker immediately dismissed Robert Shimer’s case, for he and Anne had not lived together as husband and wife since 1911. Parker noted that since the chemist had not filed for a patent for her inventions, he could not award her estate any money for them. He rendered his decision on October 30, 1925 and granted her estate, which had previously been awarded $3,900 for the missing jewelry, an additional $7,525.00. Her mother’s estate received $7,500, as did her sister Maibelle.

Anne Shymer’s sister, Maibelle Heikes Justice, was a successful author and screenwriter. May 1915 found her in Los Angeles, where she received a happy letter, from her mother, describing Anne’s departure.

"The letter came but a few minutes before we heard of the terrible fate of the Lusitania. It was such a happy letter. Mother tells me how sister was overjoyed at meeting an old friend who was in Mr. Vanderbilt's party. It was a jolly crowd.

"The letter came but a few minutes before we heard of the terrible fate of the Lusitania. It was such a happy letter. Mother tells me how sister was overjoyed at meeting an old friend who was in Mr. Vanderbilt's party. It was a jolly crowd.

The ship was delayed in starting. Mother stood on the pier and sister leaned over the railing. The sky was overcast. Just as the gangplank was going up, a messenger boy ran on the dock and, dashing up to Mr. Vanderbilt, handed him a note. It was a note of warning, telling Mr. Vanderbilt not to sail at peril of his life.

Mr. Vanderbilt laughed quizzically and showed it to the rest of the party. At that instant, the sun burst forth. It played directly on my sister, Anne. Mr. Vanderbilt laughed, and declaring it was a good omen, threw the anonymous letter away.

The picture of my sister Anne standing there with the sunrays shining directly on her, was the last my mother saw of her. We have had no good news, nothing but messages telling us to keep up hope.

I am sure my brother-in-law was not on board, or my mother would have mentioned it in her letter. And I think he is busy right now on some proposition that would have kept him from sailing.

The ship's records have his name, but not my sister's. They must mean Mrs. R.R. Shymer, and not her husband. She is reported as missing, and there is very little hope for any of the passengers that have not been saved already.

Anne was starting for London to organize a branch office for a large chemical concern of this country. She is a university graduation widely known as a student of chemistry.

Maibelle Haikes Justice wrote films for stars such as Tom Mix, Mary Miles Minter, and Buck Jones. Her career in Hollywood ended around 1920. She died at age 54, in 1926.

A second inventor traveled aboard the Lusitania, but his intent was considerably less benign than that of Anne Shymer. Henry ‘Harry’ Pollard was returning to England with a formula for poisonous gas to offer to the British government.

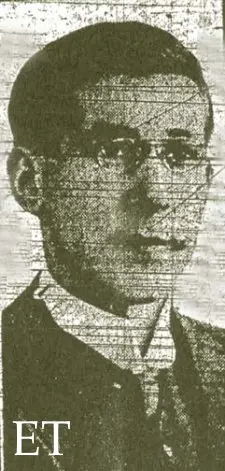

Henry Pollard

(Michael Poirier)

He was born in Bradford, one of several children of Mr. and Mrs. of Edwin Pollard. The family moved to Old Corn Mill, Silsden where spent most of his childhood. He was educated as an engineer’s draughtsman. He was also an inventor and was said to have obtained several patents. One of his later discoveries involved the use of liquid ammonia in the manufacturing of ice.

Pollard left the United Kingdom, in 1914, to work on projects in the United States. He traveled aboard the Transylvania, which arrived in New York on December 16, 1914. His destination was Washington D.C. where he was to stay with an acquaintance named Middleton and work in the Victor Building.

Henry was installing machinery for an ice plant when an explosion occurred. It left several men unconscious and another near death. The cause of the explosion intrigued Pollard, and while investigating its origins, he believed that he found something that could help offset the effects of the gas bombs used by the Germans. He spent much time refining his discovery, and as he did so, the nature of its potential changed. Pollard began refinining his discovery for use as a weapon, and when he was done, he believed that it would prove to be far more destructive than anything invented by the Germans. He booked first class passage on the Lusitania, determined to offer his formula to the British government.

Henry Pollard’s plans to help in the war effort were not to be, for he was lost in the shipwreck. His brothers Frank and Lewis traveled to Ireland, but despite their relentless search, they found no sign of Harry. The exact nature Pollard’s discovery has not been preserved; his notes were apparently lost with him. However, his work immediately before the disaster investigating the explosive potential of refrigerant ammonia suggests of what his gas weapon may have consisted. Although one regrets the loss of Mr. Pollard, it is perhaps for the best that his discovery was never utilized.

Albert Bilicke, pioneer, successful Los Angeles real estate developer, and Lusitania victim, has survived to the present as a minor character in every book written about the O.K. Corral shootout.

Albert and Gladys Bilicke

Albert Bilicke’s was a success story straight out of the Old West. He was the son of German immigrants, who settled in the boom town of Tombstone, Arizona. Albert and his father opened and operated the Hotel Cosmopolitan during the mining years, and the family prospered. Albert became friends with Wyatt Earp and his family, and testified on Earp’s behalf at the infamous trial following the gunfight at the OK Corral. Bilicke swore at the trial that he saw Tom McLaury, one of the outlaws killed in the shootout, with what appeared to be a gun in his pocket. Albert was no stranger to violence, having once shot and killed a man who threatened his father with a gun.

The Hotel Cosmopolitan burned, and the Bilicke family moved on to California. Albert operated a hotel in Santa Rosa, and then went on to Los Angeles where he ran the Hollenbeck Hotel. He met and married Gladys Huff, of Illinois; 1915 newspaper accounts claimed that she was his private secretary. Albert Bilicke began plans for his most ambitious project,the Alexandria Hotel in downtown Los Angeles, shortly after his marriage, Ground was broken for the new edifice in 1904 and it opened a year later, soon becoming one of the leading hotels in California.

Alexandria Hotel

He next formed a partnership with R.A. Rowan, co-founding the Bilicke-Rowan Fireproof Building Co. They built the Rowan Building and bought many properties in downtown Los Angeles. Albert began investing in property in Kansas City, Missouri, where his holdings were reported to be over $1,500,000.

The Bilickes had three children: Carl, Albert, and Nancy. Their home was 699 Monterey Road in South Pasadena, California. Friends and acquaintances received a lasting impression of beauty and permanence when they visited the estate. The house stood amid orange groves, and the lawns behind the house were terraced to a height of 50 feet over their residence. Below them, the valley rolled away to a view of the distant ocean.

|

| Gladys Bilicke (Michael Poirier) |

|

| Albert Bilicke |

|

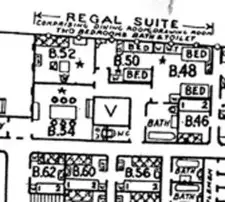

| Bilicke Cabin (B-48) (Paul Latimer) |

Albert became ill and needed abdominal surgery in early 1915. His physicians advised that he and Gladys should take a short, recuperative trip. Their short journey was cross country, terminating in New York. En route, they visited with friends and relatives in a number of cities. They stopped in Kansas City for a few days, and intended to return in time for the grand opening of the elegant Muehlenbach Hotel.

They decided, while in New York, to cap off the pleasant short trip with a voyage. Albert sent a telegram to his real estate agent, C.H. Barber, saying: “Too strenuous for me here. Am sailing on the Lusitania.” Barber did not like this turn of events at all and wired back to the Bilickes that they should not sail. It was too late: the couple had booked cabin B-48 and were ready to depart.

Albert wrote a postcard to his friend, Leonard Brown, while waiting for the ship to sail: “We are off and this is certainly a fine ship. Have crossed twice in her and am acquainted with her speed and officers. Expect to get much rest from this trip…”

The couple was resting in their cabin, after lunch, when the ship was struck. They made for the deck. Gladys and Albert entered a lifeboat, supposedly the first from the starboard side to be overturned while lowering. According to their grandson, Gladys fought her way to the surface and grasped at some floating wreckage. The family lawyer confirmed this in an interview, and said that she held onto a spar with several men. She scanned the ocean for any sign of Albert, but could not see him, and surmised that he may have been trapped underneath the wrecked lifeboat.

Several hours later, Mrs. Bilicke was brought to Queenstown. She did not rest: she later told her grandson that she spent hours walking from place to place looking at bodies, trying unsuccessfully to find her husband. A description of Mr. Bilicke was given to the American Counsel in Queenstown based on Gladys’s memory of what he was wearing that day:

Age about: 53. Height: about 5 feet 6 inches. Eyes: blue. Hair: sandy and thin. On abdomen, 2 scars from operation. Clothes: Suit, dark material. In the pocket, wallet with gold mountings containing English money and papers. Little notebooks in pockets. Watch and chain, gold and platinum. On watch is monogram, A.C.B. Ring, turquoise and two diamonds. Underwear: Linen mesh, short and drawers. Abdominal belt, silk hose, caught up with gilt clasps. Shirt marked on sleeve by monogram “A.C.B.” and back of shirt marked “Sulka & Co., Paris & New York.” Cuff buttons set with light blue sapphires. Collar, white turnover. Neck tie, dark. Stick pin, emeralds surrounded with diamonds.

Third class passenger, Miss Violet James, of Edmonton, Alberta described meeting Mrs. Bilicke, in a surprisingly insensitive letter:

I came along with a party of survivors to London. One of the first-class passengers, an American woman, lost her husband. She hung on to me all the time and she got on my nerves. We went to the Ritz, and she pleaded with me to stay, but feeling as I did, I couldn’t, for I wanted sleep. My throat sore – limbs aching. I brought her up, looked after her all along, and considered I had done my duty. However, I hadn’t left her long before a special messenger called me back, but my doctor came to my rescue and ‘phoned saying I was too ill and must stay in bed for a few days. He came to see me twice yesterday and again today. I have promised Mrs. Billick (sic), to return with her to Los Angeles, California, within the next month, so I shall have to pay you a rush visit. We sail under the American flag next, and will make sure of it, too.

Mrs. Bilicke eventually abandoned her search and sailed for home on the Philadelphia; arriving in the United States on June 3, 1915. She was met in New York by a maid and a nurse, and from there returned to California and her family. Her sister, Ella, went to Chicago to meet Gladys’ train. Mrs. Bilicke’s told Ella of the greatest fear she experienced while awaiting rescue, which was that she suspected she was being carried out to sea by the strong current.

When Mrs. Bilicke arrived in California she was surprised, not pleasantly, to learn that her husband’s will had been probated and that her sister-in-law, Louisa, was fighting for a share of the estate. Albert’s will was settled in 1922, with his wife and children prevailing. They received $3,521,540.00.

Gladys filed claim against Germany before the Mixed Claims Commission. She had been injured in the disaster, sustaining sustained several abrasions on her head and contusions on her body, although it was mainly for loss of support that she was claiming. The court noted that her husband’s net worth, in 1891, was about $16,000, and that at the height of his career, Bilicke was worth $2,706,864. Judge Edwin Parker awarded Gladys $50,000 and each child was awarded $30,000.

Mrs. Bilicke remained active socially, and maintained a residence on West Adams, a fashionable street in Los Angeles. The Lusitania was rarely mentioned in her presence, and she would only talk about her experiences in the disaster with great reluctance. She passed away on March 3, 1943 at age 77.