The Lusitania : Part 8 : A Hint of Scandal

Scandal on the Lusitania Stories

Sonneborn and Schwabacher…

The sinking of the Lusitania had the undesired effect of laying bare the personal lives of those on board. Whether it was having to make one’s financial status public before the Relief Committee, or having to return to one’s wife after the death aboard the ship of the mistress with whom one was eloping, many of those who survived saw aspects of their lives best kept submerged placed in full view. Bigamy, embezzlement, adultery, unmarried cohabitation, financial incompetence and probable homosexuality were among the private stories suddenly made a matter of public record.

The posthumous calumny directed towards Henry Sonneborn by a member of the U.S. Government’s judicial branch was perhaps the most unfortunate exposure of a Lusitania passenger’s private life. Mr. Sonneborn and his friend Lee Schwabacher were most likely in a long term gay partnership. They lived and traveled together for at least fifteen years, and died together in the disaster. A decade later, after a scathing case summary by a U.S. Mixed Claims Commission judge, a distorted version of their friendship became legitimized.

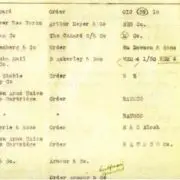

Schwabacher and Sonneborn Schwabacher and SonnebornCourtesy of Paul Latimer  Henry B. Sonneborn  Leo Schwabacher |

Schwabacher seems to have possessed considerable property. The substantial provision made by his will for his friend, Sonneborn, suggests a possible source of income to the latter, supplementing that from his own slender estate and enabling him, in middle age, to embark on the cultivation of his voice in Paris.

So spoke Umpire Edwin B. Parker, of the U.S. Mixed Claims Commission, on January 7, 1925. With these words, he posthumously doomed Lusitania victim Henry B. Sonneborn, of Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A. to an eternity of being an inside reference, for want of a better term, among researchers who have read through the Mixed Claims Commission Lusitania Case Summaries. Two men traveling together, who were “fast friends” enough to have named one another sole beneficiaries in their respective wills, who arranged to be buried together in the same mausoleum, and one of whom the court stopped just short of calling a “kept man” in its final judgment of the case seems, on the surface, to be one of the more scandalous affairs exposed by the disaster.

We approached the story of Mr. Sonneborn and Mr. Schwabacher from a sensationalistic angle in an article, and when Jim received an email from a member of the Sonneborn family a year or so later, he was initially uncertain of how his reception would be. Mark Praetorius, Henry Sonneborn’s great-nephew, proved not to be angry that we had dragged “the family skeleton” out of the closet. In fact, he quickly revealed that the relationship between the two men had never been the family skeleton. Henry and Leo had not been ostracized within the family during their 15 years together (Henry’s mother considered “Lee” a second son) and they did not become something best left not discussed within the family after the harsh official judgment in the 1920s.

Henry Becker Sonneborn was born in Baltimore, Maryland, to Philip and Wilhelmina Becker Sonneborn, on October 14, 1872. The Sonneborn family ran a tavern on Light Street in downtown Baltimore and lived in rooms above it. Henry was a graduate of Baltimore City College, and along with his brother, Louis, half owner of a successful coal distributing company.

Leo “Lee” Schwabacher was the son of Henry and Virginia Schwabacher, born on January 14, 1873, in Peoria, Illinois. The Schwabacher family made their fortune as liquor merchants, and were more than comfortably well off. The details of how Lee moved from the multi-servant family estate on Perry Avenue, Peoria, to Baltimore have not survived. He was working, as of 1900, as Louis and Henry Sonneborn’s bookkeeper, and boarding in a room over Philip and Wilhemina Sonneborn’s tavern.

Wilhelmina and her family moved from Light Street to a larger and far more elegant house at 896 Battery Avenue, after the death of her husband, circa 1900. Bookkeeper Lee Schwabacher moved with them, still being referred to as their boarder. Simultaneous to the Sonneborn family’s move, Henry Schwabacher died, leaving each of his children a share of his estate large enough to generate $10,000.00 per year income, through interest.

Henry B. Sonneborn and Lee Schwabacher began traveling together in 1906, and after 1910 Henry sold his share of the family coal business. The two men moved to Paris, France, with one another in 1911, allegedly to allow Henry to pursue a singing career. They returned to Baltimore in October 1914 for an extended visit prompted, in part, by unease over the escalating war in Europe. Lee Schwabacher purchased a mausoleum in which they would one day be entombed together, before their return to Paris in May 1915. Both men altered their wills at this time, each naming the other his sole beneficiary. Schwabacher traveled to Peoria, where he spent time with his relatives while liquidating his remaining assets there; he planned never to return.

A small article about guests of the Gotham Hotel, on Fifth Avenue in New York City, who sailed aboard the Lusitania’s fatal voyage, listed Mr. Sonneborn and Mr. Schwabacher among those lost in the disaster.

Wilhemina Sonneborn traveled to New York City and boarded the Lusitania to make a last minute effort to persuade her son to cancel his passage. His response, along the lines of “A submarine? Don’t worry- we’ll send a telegram when we arrive safely” was quoted on both May 2nd, after the ship had sailed with Mr. Sonneborn and Mr. Schwabacher aboard, and again on May 8th after they died together.

Henry and Lee vanished from the record when the Lusitania sailed on May 1, 1915. Their bodies were never recovered, and as of yet, no account by anyone who knew them has surfaced to fill in the details of their final days. George Kessler later wrote of two men, rumored to be “German spies” who kept to themselves: one can make the case that this was the German surnamed Mr. Sonneborn and Mr. Schwabacher and, if so, that their final week might have been less than pleasant.

Mark Praetorius has speculated on what his ancestors’ reaction to the loss of both men must have been. The family was proudly German and to lose loved ones in an act widely condemned by anti-German forces must have led to a number of conflicting emotions. A 1915 news clipping, kept by the Sonneborn family, is an interesting window into how the Sonneborns may have felt:

For a year Mrs. Sonneborn’s health has been gradually failing, and her sons and daughters are now experiencing the added anxiety of shielding her as much as possible from the shock of news of the ship’s disaster although the bare fact has not been kept from her. Mrs. Sonneborn, in spite of her anxiety, is bearing no resentment towards the German torpedo boat that brought disaster to the Lusitania. She was born in Wiesbaden, Germany, nearly 80 years ago and lived there with her father when he was a professor at the university until she was 20 years old. Before her marriage, she was Miss Becker. She believes that Germany has given sufficient warning to all prospective travelers on this side of the ocean of the risk they were running to place the responsibility entirely on their shoulders when disaster occurs. This opinion is also shared by Mr. Sonneborn’s sister, Mrs. Philip Praetorius who, with her husband and children, makes her home with her mother. Their German blood makes it impossible for them to forget that the Lusitania is an English liner.

Perhaps the article offers true insight into Mrs. Sonneborn’s mindset two days after the death of her son and a man she reportedly viewed as a “second son.” Yet, one wonders how, if she was being kept in seclusion and denied news of the disaster, she managed to form so definite an opinion and how she managed to articulate it to a reporter. One also wonders if, in the first stages of shock at losing their family member and friend, any Sonneborn, no matter how proudly German, would voice a blame the victim sentiment to the press. Another odd detail is that Mrs. Sonneborn, described as being “in decline” had managed to travel to NYC to plead with her son not to board the ship, as reported on May 2nd. Neither Mrs. Sonneborn nor her son was anything approaching a celebrity, which vouches for the veracity of that particular story: the press would have had no reason to invent it before the disaster had it not actually occurred. Our interpretation is that no matter how pro-Germany Wilhelmina was, she was also afraid of what Germany might do, and made a last minute attempt to keep the two men off the ship. Would an ailing woman, who made a long train trip in an unsuccessful attempt to save the life of her son and his traveling companion, be inclined to let the world know that they had brought their deaths upon themselves, just nine days later?

The Mixed Claims Commission’s posthumous opinion of the two men, particularly Mr. Sonneborn, was harsh. The most damaging part of the case summary was the declaration that Henry Sonneborn was a man of slender estate, unemployed, and seemingly being supported by Leo Schwabacher. “The inferences from the meager statements contained in the record are that the resources of decedent were slender and his income small. The property of his estate, both real and personal, inventoried only $13,107.653.” One wonders what criteria Umpire Parker was using to judge “slender.” Sonneborn’s yearly income, prior to the sale of his share of the coal business was listed as $8,400.00, a more than adequate amount upon which to survive ca. 1910, and only $1,600.00 per year less than Mr. Schwabacher was earning in interest on his inheritance. $13,100.00 was one of the larger estates left by any of the American victims. Mr. Sonneborn’s lost personal effects were valued at $2,230.50. It may be noted that Allan Loney, socially well connected Lusitania victim, was described in the record as having the earning potential of $10,000.00 per year as a broker and bond salesman, of having lost $1235.00 worth of personal property in the disaster and “…died intestate…his daughter inherited his entire estate which does not appear to have been large” without any additional editorial comment being made by the commission. Likewise, the fact that Charles Williamson not only died broke but also owed a large sum of money to some of the most socially correct residents of New York City was allowed to pass without remark, as was the fact that he was traveling with a woman to whom he was not married. It would seem that Mr. Parker was basing his evident disapproval of Mr. Sonneborn on something other than dollar figures, because by 1925 standards, Henry was far from poor.

It is apparent from the financial data presented in the case summaries, that the two friends were more or less on equal footing, and although there is no known surviving evidence of who paid for what, other than that Mr. Schwabacher bought their shared mausoleum, it is obvious that this was not a case of an opportunistic poor man bleeding a well off friend.

Thomas Snowden, of Lynn, Massachusetts, was another survivor who saw a personal scandal made public as a result of his Lusitania experiences.

The shoemaker was returning to his native Leicestershire, where he was born in 1885, to visit with friends and family and, perhaps, to enlist. His excellent first person account omits but a single significant detail regarding his experiences aboard the ship:

I never want to go through such an experience again. To see men, women and little children drown in hundreds is a sight one will never be able to blot from one’s memory. I have worked hard since I left Leicester, and with hundreds of others on the boat was looking forward to a happy holiday and a happy re-union with my friends. To think how happy we all were up to the moment of the disaster, and now – it seems like a horrible nightmare.

I had just got up from lunch and was making my way along the second-class deck when there was a terrible crash and the ship shivered, as it were, from stem to stern. In a moment there was pandemonium. People were running around in all directions, and probably the majority of them realized that the ship had been torpedoed. The captain and officers certainly realized it for steps were immediately taken to put the women and children, or as many as were possible, in the boats.

I and my friend did what we could in this direction and whilst we were assisting a very heavy lady, there was much screaming. I ran to the side and looked over. Then I knew the cause of the agonizing cries. About 50 women and children were struggling in the water, appealing for help. It was heartbreaking to see them sink and disappear. The ropes of the boat had gone wrong, and the boat had been smashed against the side of the ship.

There was another crash. Everybody seemed to realize that it was a case of life or death. As many of the women and children were ‘collected’ as possible, but there were hundreds of poor things who never got a chance. I realized that the ship would sink, took my boots and coat and waistcoat off, and when I felt her going – dived. It seemed eternity before I struck the water. When I came up, I seized a piece of wreckage and held on to it. In the meantime the great ship disappeared. She went with a plunge – nose first.

Some distance away, there was a life raft. When I reached it there were some twenty-four of twenty-five other persons on it. The number was gradually added to and eventually this too began to sink. Far out was an overturned boat. I jumped off and swam to it. Others were doing the same. I reached it and with help got it righted. Those who were with me then began to pick up others. Among those I helped to pull in was Lady Allan. Another man I pulled in was called Beauchamp. Eventually we found the third assistant engineer among us, and he took command.

The boat contained seventeen men and five women and it was two and a half hours before we were picked up. What our condition was then, few can imagine. What our feelings were, no-one can express. When in the water I saw the body of a young fellow – Charlie Hurley – float by, apparently dead. He was from Brockton, Mass., and was coming to Leicester to work. He told me he was going to a Mr. J. Wine, 132, Tewksbury Street, who I presume, is a relative. I have looked in the list of those saved and as I cannot find the name, I presume that he was drowned.

We were picked up by a Greek steamer, flying the Greek flag. She, too, was evidently expecting to be torpedoed, for her boats were kept ready to be launched. Eventually we were landed and among the first things we were asked was whether ‘Anybody had taken a snapshot of the sinking ship?’ Sure if that fellow had not gone by quickly, he would have been molested.

I lost everything except my watch and money. I never thought we should get through. Our boat was fast making water, and could not have kept afloat half-an-hour longer. But we were very lucky, although luck is not the right word for it. You know what I mean. I am thankful, and so is one left back in America – my mother!

Snowden gave a second account to the local newspaper in Lynn, Massachusetts, on the fiftieth anniversary of the disaster:

When the torpedo hit, the ship shivered from top to bottom and from stem to stern. The concussion knocked me and everyone around me to the deck. The Lusitania immediately took a severe list to the starboard as thousands of gallons of water flooded into the hole made by the torpedo. I immediately joined other men in putting the women and their kids into the lifeboats. A lot of the boats were lowered about half way when suddenly something snapped the lines and they smashed to pieces against the side of the ship and in the water. The women and youngsters were spilled into the water and most of them drowned. Only two or three of the boats were lowered without incident. There was no question about the men escaping in the boats. There just weren’t enough!

It was clear that my only chance of surviving was to jump overboard, so I took off my shoes and socks and jumped the 40 foot from the deck to the water. It was cold. I spotted an overturned lifeboat with about 20 or 30 people holding on to it. I am a good swimmer and didn’t have any trouble reaching it about 50 yards away. We stayed in the cold water for about eight hours and during that time I saw 300 to 400 bodies scattered all over the horizon.

Finally, we spotted a ship coming towards us. The vessel named Kintina (sic) might have been an old tramp steamer but she looked beautiful to us. She was flying a Greek flag but was actually a British ship raising the German blockade. The crew, all East Indians, lowered their small boats to scoop us out of the water. Then they took us into Queenstown. When I got ashore, I refused medical care and told them all I needed was a good drink of whisky to stir me up. I decided to return to the United States, after realizing how sweet life was. I figured war work making military boots was just as vital as anything else.

No mention was made, in either article, of the fact that Snowden had been married for several years in May 1915.

Mrs. Marion Snowden sued her husband for divorce in early 1916, on the grounds of cruel and abusive treatment. She revealed, in court, that her husband had abandoned her to elope to England with another woman, from Lynn, but that she did not wish to draw the name of the woman- who drowned- into the public eye.

Mrs. Snowden, perhaps gleefully, revealed the woman’s name to the press upon receiving her settlement,. Thomas Snowden had informed his wife, around April 1915, that he was leaving her and returning to Leicestershire with Mrs. Eva Finch. Mrs. Snowden did not object, in light of the abusive treatment she had received during the course of her marriage. A 1916 newspaper trenchantly commented:

Snowden and Mrs. Finch sailed on the Lusitania. When the vessel was torpedoed, Snowden was rescued but Mrs. Finch was drowned. At the time, reporters noted that neither Mrs. Snowden nor Mr. Finch expressed any interest in the fate of their mates.

Thomas Snowden died in Lynn, on February 15, 1966, at age 81.

Aino Antila had immigrated to the United States from Finland at some point prior to 1910. She had two sons, Carl in 1911, and Jan ”John” in 1912, in Rockledge, Michigan. She and her sons were deported to Hanko, Finland by way of Liverpool during the summer of 1914; traveling aboard Cunard’s Carmania as part of a large group of Finnish deportees. The Antilas arrived in Liverpool on August 7, 1914, and a day later were placed aboard the Cunard liner Laconia and deported from England back to the United States. The entire family was detained upon arrival in New York, on August 17th, and hospitalized at Ellis Island. The separate paperwork pertaining to the nature of the illness, and who among the family was ill, has not been placed online. Cunard, as the shipping line which accepted these undesirable immigrants, was compelled to pay Ellis Island for their upkeep. The Antilas were detained at Ellis Island until January, 1915, and then held elsewhere until the following April, when they were again deported. They boarded the Lusitania, as third class passengers, and on May 7th were among the handful of families to survive intact.

The Cunard Line later sued the U.S. government for the approximately $50 it paid for the upkeep of the Antila boys during their internment at Elis Island. Their rationale was that only Mrs. Antila was a ward of Cunard; the boys, as U.S. citizens, were not the company’s responsibility. The suit was decided in Cunard’s favor, and the cost of maintaining the brothers from August, 1914 thru January, 1915 was refunded to the company.

“Constance Eda Stroud gave birth to a child of which your petitioner is not the father…”

They say looks are deceiving. Edward Stroud, his wife Constance, and daughter Helen appeared to be a typical family sailing home aboard the Lusitania. Passengers they encountered had no reason to believe otherwise. In reality, the fair haired couple with the red headed daughter was divorced, and the reason for the divorce was an illegitimate child – Helen.

Edward Percy Wallace Stroud was born in early 1877 to Colonel Henry and Ann Stroud. He grew up in Ramsgate and Eastbourne as the middle child of eleven children. When he was of age he signed up for the Navy and served in the Mexican war as a ACV/Sub Lieutenant. A few years later, he met Constance Eda Simpson, daughter of Charles and Alice Simpson of Streatham. They were married in a civil ceremony on August 19, 1907 at the Christ Church in Mexico City, Mexico. A second ceremony followed less than a month later, on September 3rd. They settled into their lives, while he first worked as the manager of the American Creamery Co. and then as the marine superintendant of the Anglo Mexican Petroleum Co.

Constance made frequent trips home to visit her family, and on March 19, 1912, she gave birth to Helen Wallace Stroud at the hospital in Westminster. A year later, Edward Stroud sailed home on the Oceanic, and began divorce proceedings in June. He wrote out the reason in his deposition:

“That the said Constance Eda Stroud had frequently committed adultery with a man whose name is unknown to your petitioner. That on March 19, 1912, at the Westminster Hospital in the county of London, the said Constance Eda Stroud gave birth to a female child of which your petitioner is not the father.”

How he came about this information is unclear. Did a friend or family member warn him? Did Constance send a confession? Did he always suspect the child was not his? Although a co-respondent was not named, the court felt that Edward had proven that Constance had committed adultery, and agreed for the dissolution of the marriage. The final decree was reached on December, 19, 1913 and the marriage dissolved on June 29, 1914.

That was not the end of the marriage, however. Constance began a series of regular trips to Mexico, with Helen, to visit Edward, with the first commencing less than a month after the final decree. Was a reconcilliation in the works? It is hard to say. The final trip was in March 1915, and the three of them booked passage on the May 1 crossing of the Lusitania. Mrs. Stroud and Helen traveled from Mexico to New York separate from Mr. Stroud, aboard the San Urbano, and checked in to the Phildelphia Y.W.C.A., before traveling on by train.

Second class was over-booked, but the ex-spouses were befriended by the gregarious Archie Donald and Mr and Mrs. Cyril Pells. Edward, having served in the Navy, chatted with several men who were going overseas to join up. People apparently did not know the Strouds were divorced, and it was not noted as such. They appeared to blend in with the many young families with children.

Edward was on deck when the torpedo struck, and Constance was below. He brought his family on deck, and made two subsequent trips down to the cabins for lifejackets. The final trip back on deck had him climbing on his hands and knees due to the sharp angle. Archie Donald saw them on deck, and watched as Edward stripped Constance of her clothing so that she would be able to swim better. He held Helen in his arms during the plunge, but lost his grip. Edward and Constance survived, but Helen was gone. The former Mrs. Stroud supposedly lamented to Donald, “Well, we will have another.”

Whatever bond that tied them together soon evaporated, and by the end of 1915, Constance had married Francis John Newton Dunne. Edward married Dora Williams a few months later . Both of these marriages would be short lived. Francis became a Captain in the Royal Field Artillery. He died on December 9, 1918, possibly of an injury suffered during the war. Constance was overcome by the news. She ingested a narcotic that put her into a coma, and passed away on December 10.

History repeated itself, and a year after Edward had married, he was in court divorcing his second wife on the grounds of adultery. This time a co-respondant was named.

Having received an opportunity elsewhere, he boarded a ship in 1923 bound for South Africa. He became a Senior Cultivation Protector. While there, he met Ethel Mary Bisgers. They married and had a son, Edward Peter. They decided to raise their family back in England, and returned in October 1930 on the Llangibby Castle. Ethel died in the first quarter of 1941 on the Isle of Wight. Several years later, when Edward was living in Wimbledon, the pain of the past was erased when he succumbed to mycardial degeneration on March 9, 1949.

Constance Stroud Dunne’s grave

Courtesy of Peter Kelly

Rose Ellen Murray, of Dublin and Boston, became a minor celebrity after she survived the Lusitania disaster. However, her celebrity proved to be her undoing twenty years after the vessel was destroyed.

Rose Ellen was the wife of a U.S. Naval officer, Christopher Murray. She loved ships and travel, and crossed the Atlantic at least fifteen times between 1910 and 1926. She would claim 34 crossings, a number which remained constant in her press releases between 1925 and 1932, despite other voyages made in the interim.

Christopher Murray and Rose Ellen Murray

Mrs. Murray’s frequent appearances in the papers hinged on her claims of being a survivor of both the Titanic and Lusitania disasters. She would tell eager reporters of her long wait for the Carpathia, and of her hours spent atop an overturned Lusitania lifeboat. The latter, at least, could be proved true. She had jumped from the sinking liner and been saved from atop a lifeboat, as had her brother, Patrick Ginley. Mrs. Murray was a good sport, gave great quotes about how she loved “the sea to the extent that she cannot now sleep on land” …and if her Titanic story seemed sparing in details compared to her Lusitania account, no one questioned. She was also aboard the Celtic when that liner was involved in a minor collision and apparently added that tale to her recitation at some point.

Mrs. Murray maintained a home for her husband and two of her brothers on South Circular Road, in Dublin.

One day, in July 1935, Mrs. Murray was accosted at her residence by three young women who said that they were there to escort her to a mental institution. Mrs. Murray refused to go with them and, instead, went to The Four Courts in Dublin, in order to discuss the situation with her lawyer and to instigate legal proceedings against an unnamed party. There, she was again confronted by the three women. A scene ensued when Mrs. Murray learned that they had been sent to take her to Verville, a private mental hospital. She was forced to her knees and her arms restrained. The women pulled Rose Ellen into a taxi with great difficulty, and broug

ht her to the facility. She remained in Verville from July 5, 1935 through October 10th.

Mrs. Murray was released after a sanity hearing determined that she was sane and capable of maintaining her own affairs. Incredibly enough, it seems that someone used Mrs. Murray’s frequently told Titanic, Lusitania and Celtic stories, and an incident in which Rose Ellen had been blackmailed over some indiscretion, to have her committed. She proved by affadavit and other evidence, that all four claims were partially true and not melancholy ravings, and was released. The identity or identities of whoever had her committed was not made public, but the fact that Mrs. Murray thereafter lived apart from her husband and brothers seems to point a finger.

Her actual Titanic story, as sworn in court, was that she was supposed to have been aboard the ship, but did not sail due to a missed train. This was far different than the tale told to the pier side press in NYC and Boston, and conceivably true.

Mrs. Murray sued Dr. Sullivan, of Verville, in November 1939, claiming that she had been falsely committed, and was physically assaulted by another patient while in the hospital. She had been punched in the face, driving her eyeglass in to her eye, and when she complained was told that she had to learn to watch out for herself when “in a place like this.” The jury found in favor of Doctor Sullivan in December, stating that Mrs. Murray had been legally committed with papers filed June 28, 1935, and that the assault was not due to specific negligence on his part.

Rose Ellen Murray was found dead on the floor of her home at Merrion Square, Dublin, on January 12, 1942. She was 62 years old. Rose left an estate of three thousand five hundred pounds. Her husband and three brothers were bequeathed fifty pounds each, and the bulk of her money went to charity. Her brothers opposed the will, and in July 1942 were each granted an additional two hundred pounds. Her husband, still in naval service, wrote the court to say that he in no way wanted to interfere with his late wife’s wishes.

I love the sea. It’s strange. When I’m on land I’m all nerves. Often I can’t sleep. Time after time, I live through it all again. When I’m at sea, I forget it all.

I remember that Rita Jolivet and I had been taking up a collection for the ship’s musicians. My brother rushed to me with a life belt.

The ship was about to stand on end. I leaped from one of its highest decks. An old man caught me by the hair. He was clinging to some wreckage. In a few moments, he went under.

I swam to an overturned lifeboat, and crawled across it. I lost consciousness.

They wrapped me in a blanket and took me to a hotel in Queenstown. There someone gave me a pair of pajamas.

I took a train that afternoon to my old home in Belfast. Still wearing the pajamas, without shoes or socks.

Rose Ellen Murray; disembarking from the Caronia. NYC, 1926.

Patrick McGinley, Rose Murray’s brother, was formerly a teacher at St. Gall’s National School, Clonard. He had been an employee of Park and Telford in New York City for five years as of May 1915, and was returning to Belfast for his first visit home since emigrating:

I had lunched at the first table at one o’clock, and then I came on deck and chatted with a gentleman friend. Everyone around was in the best of spirits.

Shortly after two o’clock as I was still talking to my friend, I noticed a white object about 100 yards off on the land side. It was directly at right angles to the liner. I called my friend’s attention to it, and he said “That appears to be a periscope.”

I saw a white streak coming towards the vessel. “My God, there’s a torpedo” exclaimed my friend. I saw it come quickly through the water until it struck the ship, which shook like a reed in the wind and heaved to one side.

Everyone was rushing to and fro and there was a good deal of excitement but not all that much under the circumstances. The people got into the boats as quickly and with as little crushing as possible. When they had been there for about five minutes, an order came from the captain, indirectly, that the passengers should leave the boats as everything was safe and they were going to make for land.

I at once went down to my stateroom and secured two lifebelts, thinking they were the best thing in the circumstances. On coming up, I fixed one on my sister, Mrs. Murray, who was already in a lifeboat and I fastened the other on myself. I remained in the boat, which contained about one hundred people. Orders were then given to lower all the boats quickly, as the ship was sinking very fast.

Something went wrong with the pulley on the boat in which we were, and a young man cut the ropes thinking, of course, that the boat would fall on its keel in the water. Instead of that, however, it turned upside down and we were all precipitated headlong into the water.

I went down ever so far in to the sea, and at last I began to rise again. On coming up, I felt something resting on top of my head, and on putting up my hand I discovered it was the upturned boat from which we had fallen. With great difficulty, I managed to get from under it, and I then started swimming around in the hope of finding my sister. I could find no trace of her, though bodies were drifting past me all the time.

In the meantime, the Lusitania had disappeared.

After I had been swimming for a considerable time, I managed to get onto a raft and drifted for about half a mile. I saw a lifeboat upside down and with about forty people clinging to her, and I thought if I could get to that boat I should be alright. I sprang from the raft and swam the one hundred fifty yards which separated me from the boat, and I was dragged aboard.

We were on that boat almost an hour- seven women and the rest all men. One of the men had his arm torn almost completely off, and a young man severed it for him with a pocket knife.

As we were floating about, I saw a lady and a gentleman clinging to a piece of raft and coming in our direction. When they came near the boat, the lady lifted one hand and said “For God’s sake, save me!” One man on the boat said “If you bring any more on the boat, it will go down” I said “We can’t see people drown, let’s get them on!” Mr. Wyle, a steward, and I helped the lady on, and also the man. The lady, it afterwards transpired, was Lady Allan.

Patrick McGinley died in 1951, at Cathcart, Scotland.

Several accounts bolster the unbelievable-seeming claim McGinley made about the crewmember with the severed arm. George Harrison, a third class passenger, gave this account to his local newspaper:

A young Ryhope miner, was among the survivors of the ill fated Lusitania, was bravely unselfish in the hour of his greatest danger. His name is Mr. George Harrison, of 8 Thompson Terrace, Ryhope, and he was returning from Coal Creek, Canada in order to join the army. When the vessel was torpedoed he twice gave up a lifebelt he secured, in each case to a young married woman with a child.

Mr. Harrison in an interview, said after the explosion he went to his bunk to get a lifebelt, and heard water like a river rushing into the ship. “I hastily reascended” he remarked, and happily found another belt in a first class state room.

Upon reaching the deck Mr. Harrison saw the first boat launched, but it broke up against the vessel’s side as the Lusitania rapidly listed. There were four people in the boat and one of them, a man, had his face smeared with blood. A second boat was also launched but it met with the same fate.

“Immediately afterwards,” said Mr. Harrison, “I dived into the sea with a lifebelt. When I came to the top again the Lusitania‘s stern was lifting and the propellers showing partly out of the water. A few seconds later the great liner lurched and dived into the depths.

“The ocean was calm, and I clung to some broken boxes. Then I saw a young Irish girl floating near, and I managed to get hold of her. Another young fellow joined me later, and eventually we made our way to an upturned boat, which was supporting 48 others. We were the last to join it.

“Dead bodies were almost everywhere,” commented the surviving miner,” and we sometimes collided with them. Men, women, children were floating head downwards all around us, and some were wearing lifebelts. There were scores of them, and the sight was awful. For over two hours I and the other passengers clung to the upturned boat, and then we were rescued by a merchantman.

“One man” concluded Harrison, “had his arm severed just above the elbow. He was one of the crew and said he received the injury through being in the part of the ship struck by the torpedo.”

Carl Elmer Foss…

Dr. Carl Elmer Foss, of Montana, was one of a group of doctors traveling on behalf of the Red Cross. His fall from grace a few years after the sinking is made all the more surprising when it is contrasted with his behavior on May 7th, 1915.

After joining the Lusitania we saw warships outside New York harbor, and we spoke with one man of war with whom messages were exchanged. Towards the latter half of the voyage, I was told a battleship had passed us, and that some time on Thursday night our officers had received some sort of message, but as to its substance I know nothing. During Thursday night, our ill fated ship steamed with portholes covered and lights down.

About an hour before the catastrophe I was on deck. I saw something about a quarter of a mile distant, which looked to me like a boat. I could not imagine, however, that a small boat would be so far out, so I got an open glass and with the aid of this glass I could discern that this distant object was causing quite a wave of water on the shore side of the Lusitania. More than one of the watchers said “That looks like a submarine.” We were going slowly, probably at a speed half to two-thirds less than at an earlier stage of the run from America.

Luncheon was being served to the second luncheon party. Just as we finished the meal I, and many others, heard what I should describe as a loud boom. Everybody in the luncheon saloon realized that we had either struck a mine or had been torpedoed.

We were not particularly excited, but when we went on deck, the Lusitania, we found, was already beginning to list and every succeeding moment the listing movement became faster. I managed to get hold of a life preserver. Several of the crew were getting into life preservers themselves.

I jumped from the high, or port side, in to the sea, and I struck water not far from the propeller. Suddenly, down came a boat from the davits with a crash. Several people were in it. It was smashed, and I noticed one man clinging for dear life to the wreckage.

In the turning over of the boat, of which I spoke of being smashed, one man was killed. In three instances I tried to restore animation but without success. The victims were beyond human aid. While trying to drag one man away from the revolving propeller, I felt a blow in the back. This was from a piece of floating wreckage. I felt the blow severely for a time.

By this time both women and children were coming overboard, throwing themselves from the port side, with a sheer drop of at least 50 or 60 feet. I left the injured man still hanging by the rope of the wrecked boat and got hold of a woman and child who were nearest me.

I noticed that another boat had been lowered and was standing on its keel. I just held the woman and child until I got close to the second boat. I got them both on board. I noticed that the boat was manned. There were four or five men in it. They were sailors.

As the Lusitania took her final plunge the boilers, I think, must have exploded because an immense amount of steam and smoke were emitted. As she finally disappeared from view, I noticed that several lifeboats were still attached to the blocks.

I swam off towards a lifeboat, which was afloat 200 or 300 feet away. There were women in it. They were much distressed, and I did all I could to pacify them. The boat was in such condition that bailing was necessary.

The men became excited when they realized that it was sinking. At last it capsized completely. I held one woman on to the keel of the upturned boat. We got it righted. Several women were still in the water.

Suddenly I spied what I should call a canvas raft, very nearly a quarter of a mile away. I seized an oar, and getting one of the women on to one end I grasped the other, and in that way piloted the waterlogged boat to the raft. Upon the raft were four or five men. By the time I reached it, I was not able to climb over its slightly raised sides, and I was assisted. One of the women appeared to be in dying condition.

I told her I was a doctor, and I would do my best to help her. This I did, working away for some time. After the lapse of nearly forty minutes I had the satisfaction of finding that I had been able to revive her.

A short time elapsed and a steamer, the Indian Empire, I believe, came up. I did what I could to assist the rescuers, but I was so exhausted after the effort that had to be pulled aboard myself. In the boiler room there were at least fifty survivors.

I think that on the whole there was more disturbance among the crew than among the passengers. Had all the boats been lowered, there would have been a greater saving of life. The passengers were most active in assisting in getting the boats lowered, and members of the crew did that too, So far as I know there was only one boat drill during the trip.

Dr. Carl Foss returned to the United States, where he resumed his practice in Havre, Montana, in July 1916. He became embroiled in a bitter property dispute with neighbor Jake Krause, which culminated with Krause being gunned down in November 1917, shortly before the dispute was to be heard in court.

Foss and his ‘gang’ were arrested for the murder, and in October 1919 he was sentenced to one year and one day in Leavenworth Penitentiary for his role in the affair. Paroled, Carl Foss returned once again to Havre, where he died of acute nephritis, after an operation for appendicitis, on February 25, 1924. He was 36 years old.

“This looks like a fine boat and I cannot help feeling proud that the British flag rules the British waves, and I have no fear of the German submarines. There is quite a crowd on this boat and apparently they are not afraid.”

Alfred Russell Clarke, a first class passenger, wrote in a note to his son Griffith before the Lusitania sailed. He did not have time to be afraid of submarines; he was too busy with plans to expand his business by securing leather contracts with British Army.

Clarke was an ambitious man. Born in Peterborough, he moved to Toronto at age 18 and founded A.R. Clarke & Company, Limited, which eventually became the foremost producer of patent leather in the British Empire. His factory employed over 350 people, and produced leather linings, leather vests, moccasins, and other articles of leather clothing. He was married to Mary Louisa, and had a son, Griffith, and a daughter, Vivien. He belonged to many organizations including the Riverdale Business Men’s Association; Toronto Housing Co.; Toronto Civic Guild; Canadian Manufacturers’ Association, Ontario Motor League; and Masonic Order. He was also the treasurer of the Metropolitan Methodist Church.

Clarke was comfortably settled in a chair on the top deck, on May 7th:

There came the sound of a loud explosion. Fragments and splinters flew all around and a great torrent of water was forced up by the explosion and poured over the deck. The ship instantly took a severe list… The stairway was already crowded with people trying to get life preservers… I started to go to my cabin, but found it difficult owing to the angle and I returned to the upper deck.

Clarke stood at the back of the crowd, adhering to the rule women and children first, and did not push his way forward. Talking with others, he heard that the Captain had ordered that boats not be lowered:

As the list grew greater, I again tried to reach my cabin for a lifebelt. The cabin was utterly dark. I felt to remain there I would be caught like a rat in a trap. The cabin door closed as I entered… I was distressed to find the door jammed… I could not open it owing to the acute angle of the ship, but got out through a side door, and mounted the deck again.

(Author’s Note- He had a small inside cabin, D-3, which on the original deck plan for the Lusitania appears not to have had a connecting door. However, one may have been added later or, more likely, he may have upgraded while onboard to a cabin that did.)

He met a young man who had sat his table in the dining room. He was tying on a lifejacket and asked Clarke if he wanted one:

I took it and as it was impossible to stand upright, I suggested to my companion that we should take no more chances, (and) to try for a boat… He said: ‘Oh no,’ and that was the last I saw of him…Glancing over I saw two boats being lowered jammed together and trying to get free. The other boat was trying to shove off from us. The four great funnels were now hanging at such an angle as though they would soon touch the sea. Then I was torn down in the whirlpool. I seemed to touch the very bottom of the ocean.

Clarke felt something gripping his chest, “Crushing me. Something else seemed to wrench me around. I was twisted and racked. All this time I was fully conscious. I remember hoping this would soon come to an end. Suddenly, what was holding me let go, and I rose rapidly to the surface.” The next thing he recalled was floating near a boat, and two sailors pulling him aboard. The only person he recognized was fellow Canadian Leonard McMurray. “The sea was full of people. There were perhaps five or six boats around. Bodies floated by us. The corpse of a baby clung to the bottom of our boat. We could not reach it. A woman floated by, foam coming from her mouth. I put out my hand, but as I touched her hair, she passed away.” They drifted about for three hours until they were rescued.

Leonard McMurray

Clarke did not remain in Queenstown long before making the trip to London. He called for doctors to attend to his injuries once settled in the Hotel Cecil. They discovered that he had a broken rib, and he was taken to the Fitzroy House Hospital. His temperature rose to 102 and the doctors found that the broken rib had affected a lung and pleurisy had developed. His wife, Mary Louisa, was sent for at once, and she sailed for England; arriving in London on June 12.

Pneumonia set in. Mrs. Clarke at first was optimistic about her husband‘s condition. She sent telegrams home saying that his improvement was “more than maintained” and that great hopes were entertained for his recovery. Griffith Clarke intended to come also, but his mother told him it was not necessary.

Alfred, unfortunately, took a turn for the worse. His family received two telegrams. The first: “Your father very weak. Mother very discouraged. Time very short. Advise you not to come” and the second, received shortly thereafter; “Mr. Clarke is sinking rapidly. We are with your mother and will give her every attention.”

Alfred Russell Clarke died on June 20. A family friend cabled Griffith and Vivien, “Your father passed peacefully at 9:20 tonight. We will take care of your mother and arrange everything for her, including her passage and your father’s home. Cable me any instructions.” Mrs. Clarke came home on the Lapland and proceeded to Toronto with her husband’s body.

Clarke left an estate of $521,825.28, part of which was comprised of $34,845 in life insurance and $50,000 in accident. His real estate holdings were valued at $41,140 and the fair market value of the stock in A.R. Clarke and Company, Limited was shown to be $393,000. Griffith Clarke was appointed managing director of the A.R. Clarke Company.

Griffith died in 1923. His mother alleged that he ran the family business into the ground, in her case against Germany. She sued for compensation on the grounds that had her husband survived, the business would have prospered. How true this is, cannot be determined, but what is known is that Mrs. Clarke herself had an active interest in the company. She took full charge when her son died,. She was drawing a salary of $24,000 a year at the time of the 1925 hearing. Mrs. Clarke’s claim totaled $125,000. Commissioner James Friel was not sympathetic to the various claims and awarded the widow $7,500, which he deemed ‘fair compensation.’ He stated that “the insurance money alone at her age would have purchased for her an annuity of over $6000 a year. I do not think it can be said she suffered any pecuniary loss resulting from the death of her husband.”

Hickson’s, a styling house in New York City that specialized in both high fashion and select ready-to-wear, was another internationally famous business run into the ground by an heir, after the death of its founders aboard the Lusitania.

Caroline Hickson Kennedy, 53, and Catherine Hickson, 57, were sisters. Mrs. Kennedy had advanced her brother, Richard Hickson, a sum of $800 to establish himself in the women’s garment industry in 1902. She began working for the company at an approximate salary of $50 per week plus expenses, which by 1915 had increased to the sum of $5000.00 per year.

Left: Catherine Hickson; Right: Caroline Hickson Kennedy

Miss Hickson had subsequently been brought into the company at the same initial rate as Mrs. Kennedy. Mrs. Kennedy apparently designed the apparel sold by Hickson and Co, but the bulk of the money went to her brother who had a yearly income from the business of $30,000.00. The Hickson’s showroom was at Fifth Avenue and East 52nd Street, directly across the street from the William K. Vanderbilt mansion.

The sisters were embarking on an extended Parisian buying trip for their business when they were lost. Caroline Hickson Kennedy had traveled to Europe aboard the Lusitaniaon one of the early 1915 crossings, and her presence aboard the ship had prompted the Cunard Line to urge other fashion buyers to get over their war fears and head to Europe for the spring buying season. One of the sisters was quoted, on May 1st 1915, as saying, “They wouldn’t dare!” regarding the submarine threat.

Neither sister survived. Lost with them was a wardrobe and jewelry collection valued at $14,000.00. Church bells along Fifth Avenue were tolled in their honor a week after their deaths. Caroline Hickson’s body was recovered (#160) and returned to NY aboard the Cymric on June 2, 1915. She was buried alongside her parents in Toronto’s Mount Hope Cemetary.

The profits of Mrs. Kennedy’s designs in the last completed work year of her life were $125,587.56, according to the paperwork provided at the subsequent court case. The net assets for Hickson, Inc. for 1915 were $179,078.98 “exclusive of goodwill” but after that, things fell apart, and by 1920 the business had failed.

Richard Hickson claimed it was Caroline’s “genius as a designer of women’s apparel and her peculiar and exceptional business abilities” which had kept the company afloat. The court pointed out the odd disparity between what she brought in by her labors and what she was paid by her brother, and also pointed out that released from her “exceptional business abilities” Richard Hickson had withdrawn $50,000.00 from the company to establish a fashion industry magazine for his son which was “a complete failure and the investment a total loss” and had also spent about $100,000.00 on furniture and fixtures in 1915/16. Richard Hickson would be awarded $14,000 for the lost personal effects of his sisters.

Shipbuilder Albert Lloyd Hopkins, 44, died aboard the Lusitania leaving a wife and a seven- year- old daughter, both named May. The resolution of the case that Mrs. Hopkins, who remarried and was going by the name of Mrs. Ellison Gilmer, brought against Germany was one of several that make present day readers feel vaguely uncomfortable.

Albert Hopkins

Albert Hopkins had worked for the Newport News Ship Building and Dry Dock Company since at least 1904, a year in which his salary was $4,000.00. He was the president of the company by 1915, and earning a yearly salary of $25,000.00. He was physically slight, but healthy and active, and his life expectancy was measured at 25.5 years beyond 1915.

Hopkins’ death left his widow and daughter in dire financial straits:

In the testimony offered on behalf of the claimants great emphasis is laid on the fact that the responsible position which Mr. Hopkins occupied in the business world, and his station in life, necessitated his spending his entire salary in maintaining himself, his wife, and their child. As one witness expressed it, “the demands and scale of living imposed on Mr. Hopkins in his home life by reason of his high connections in the business and social worlds” consumed his entire salary. Another witness testifies that there were “no signs of Mr. Hopkins having passed from the stage of a salary-consuming man of business to the stage of a saving and investing man of business.” The inference is that business as well as social considerations influenced him in spending his entire salary, which constituted his only source of income, in maintaining his domestic establishment.

He carried a life insurance policy of $10,000.00 payable to his estate, which was collected and disbursed by his widow as administratrix in paying the debts of the estate and the costs of administration. This left his widow and her young daughter without any source of income save the widow’s personal exertions and the generosity of members of her family, who were not, without personal sacrifice, financially able to support them.

In other words, the Hopkins were what a future generation would call “$50,000.00 per year millionaires;” living a showy lifestyle, but without savings or investments and carrying substantial debt.

The court award of $80,000.00 to Miss May Hopkins seems just compensation. But, in light of the hard line taken with Edith and John Williams by the court, the award of $50,000.00 to the remarried Mrs. Hopkins seems inexplicable, since her dire financial straits were, ultimately, half of her own doing, and several other remarried widows saw their settlements negated by the fact of their remarriage.

David Loynd, Baptist missionary and Evangelist, and his wife, Alice Grimshaw Loynd, led a roving life.

David and Alice Loynd

Their travels took them from Africa, to Canada, to Chattanooga, Tennessee. But, they always returned to David’s hometown of Bolton, in the U.K. Their known travels within North America consisted of:

1896: David, single, arrived on the Majestic. Listed as an “Evangelist,” en route to Chicago.

1896: David and fellow missionary left Chicago for Lake Chad, Africa, via NYC.

1900: David, single, arrived on the Germanic, as an “Evangelist” en route to Newburgh NY.

1905: David and Alice Loynd, Mary Grimshaw, entered Canada as “Missionaries” to Hamilton, Ontario.

1906: Same party, to England via NYC.

1907: David and Alice Loynd, Mary Grimshaw, plus entire Loynd family; consisting of David’s widowed mother, brother, sister in law, niece and sister arrived on the S.S. Sicilian. Glasgow to Boston. The family was en route to Chattanooga, Tennessee.

1910-1911: Preached at Thompson, Illinois.

1913: David and Alice arrived on the S.S. Haverford to Philadelphia. They were en route to Mr. Pridgeon’s Bible School, Pittsburgh.

1914: David and Alice arrived on the Devonian, to Boston. David was listed as a missionary, en route to Thompson, Illinois. Last US residence, Midway, Illinois.

April 1915. David and Alice left Ottawa, Illinois. David preached three weeks at the North Side Mission, Richmond, Indiana, while staying with Mary Grimshaw. They traveled to NY via Pennsylvania.

Courtesy of Cliff Barry

Go From Richmond to Make Sea Trip on Wrecked Liner

Mr. and Mrs. David Loynd Visit Miss Mary Grimshaw- Local Relatives Believe Them Dead.

Leaving Richmond fifteen days ago, refusing to heed warnings of danger, Mr. and Mrs. David Loynd, who spent a month visiting Mrs. Belle Thompson and Miss Mary Grimshaw, 134 South Fifteenth Street, are believed to have perished in the Lusitania disaster.

Miss Grimshaw, who is Mrs. Loynd’s sister, and Mrs. Thompson, a close friend of the Loynds have given up hope. Relatives in Pennsylvania cabled for information regarding the Loynds and received a reply saying they had not been located.

The Loynds reside in a suburb of Liverpool. Mr. Loynd is a Presbyterian minister and came to this country a short time ago to take a church in Pennsylvania, immediately taking out first naturalization papers. He gave up his church in March and came to Richmond to visit while closing negotiations for a dry goods store in Liverpool.

The couple left here two weeks ago on Tuesday, stopping two or three days in Pennsylvania to visit. They proceeded to New York where they took passage on the Lusitania. He wrote for passage while in Richmond and had his tickets and staterooms reserved before leaving here.

Mrs. Grimshaw has written relatives in England asking for information regarding her sister and brother-in-law.

Find Loynd’s Body; Sailed With Wife Aboard The Lusitania

With the receipt of a letter saying that the body of her brother-in-law, David A. Loynd of Liverpool was recovered fifty miles from where the Lusitania sank on May 7, Miss Mary Grimshaw has given up all hope that her sister’s body will ever be taken from the sea.

The body of Mr. Loynd was recovered fifty miles east of the sinking May 21, according to the letter. Relatives took charge and funeral services were held in Liverpool where Mr. Loynd had purchased a merchandise store.

Miss Grimshaw early gave up hope that the two would be saved. Because of Mr. Loynd’s refusal to recognize fear, and confidence that he and his wife would be rescued from any difficulties, Miss Grimshaw said she believed the two would not prepare to forestall danger if it were imminent.

Mr. Loynd preached for some time at the North End Mission to accommodate the members there while the regular pastor was absent. His last sermon there was in April.

David and Alice Loynd, according to some accounts, were thrown from the first lifeboat to be wrecked. Both bodies were recovered, and David’s was returned to England for burial. Alice Loynd, body # 75, was buried in Queenstown. A photograph of Alice Loynd, in her coffin, has been widely circulated since the 1970s.

An account by Joseph Glancy, a friend of theirs from the voyage, survives. He wrote to David’s family in Bolton:

Joseph Glancy

As a friend of the late Mr. David Loynd and Mrs. Loynd, whom I met and had sweet fellowship with on board the ill-fated Lusitania, I offer you and all your relatives my sincere sympathy at the loss you have sustained. But while this is so, we must not forget that it is a gain to Christ. Both are at home with the Lord to-day. There were no two happier people on board – both rejoicing in the knowledge of Christ the Saviour. I gave Mr. Loynd my name and address and I also got his, which enabled the police-sergeant at the place where the body of Mr. Loynd was washed ashore, to wire me. I was also fortunate in having your address, although I was in the water for three quarters of an hour. I am sending you a copy of the ‘Belfast Evening Telegraph’ giving an account of my experiences; and a copy of (the) telegram from (the) Sergeant of Police at Ballinskelligs, Co. Kerry, where the body was washed ashore. ‘The body Rev. David Loynd washed ashore here this morning; your name and address in his papers; inform his friends if you know them’ I wired back to (the) Sergeant immediately giving him your address. I also wired to you and at the same time called at Cunard Offices here and gave your address. ….. With sincere sympathy, from Joseph Glancy.

Joseph Glancy’s grave

Courtesy of Gavin Bell

David Loynd was at the center of a mystery that saw him propelled into newspapers across the east coast of the United States fifteen years before his death.

An Evangelist Missing

Formerly Lived in Newburgh.

The Reverend Eben Creighton, formerly Pastor of the People’s Baptist Church of Newburgh, who resides at 16 Bridge Street, reported to the police of New York City on Weds. That the Reverend David Loynd, well known as an English evangelist and missionary, was missing and asked that a search be made for him. Mr. Loynd’s disappearance had already been reported to the police by Francis Bell, the business manager of the Christian Alliance Missionary House which has its headquarters at #690 Eighth Avenue.

Mr. Loynd came to this country on the Germanic on August 17th. He intended to do some evangelic work in Newburgh, where he had lived several years ago and from where he entered the missionary school of the Christian Alliance at Nyack to equip himself the better for the work of a mission he established at Lake Chad in the Sudan two years ago, to which he intended to return.

Mr. Loynd appeared at #690 Eighth Avenue on Saturday, Aug. 18th. He told Mr. Bell that he intended to stay with friends in Brooklyn and had ordered his baggage to be sent from the steamer to their home. He started to walk to the ferry that would take him to Brooklyn, but found that the heat made the burden of two hand bags he was carrying too great for comfort, so went into a tea store on Whitehall Street and left the bags here for safekeeping.

On the ferry he met a man connected with a banking firm in New York and they struck up so pleasant an acquaintanceship that the man accompanied him to the Brooklyn address. There he found that the friends he had intended to visit for a few days had gone to Chicago for the summer. His new friend invited him to spend the night with him, and he did.

Mr. Bell said Wednesday night that that was all Mr. Loynd told him about his new friend.

On Saturday Mr. Loynd spent the entire day looking for the baggage that the express company had taken from the steamer to the Brooklyn address. He finally found the luggage at the company’s office in Forty-third Street, and ordered it taken to the West Shore Railroad station at the foot of west Forty-second Street.

On Wednesday he left the mission house at 9 o’clock, saying that he was going to the tea store and then catch the 10 o’clock train to Newburgh. He had ample time to get the bags and catch the train.

On Thursday night, Mr. Bell got a postal card from the Reverend Mr. Creighton, who wrote asking what had become of Mr. Loynd, as Mr. Loynd had not appeared. Since then, Mr. Bell and Mr. Creighton have gone through all of the hospitals in the city and have searched the police records, but they have found no trace of the evangelist.

At 38 Whitehall Street is the tea store of Robert H. Reilly. A young man in the store said Wednesday night that Mr. Loynd had left his valises there on April 17 and had not called for them until Friday, August 25. This the friends who are hunting for Mr. Loynd find strange, as Friday was two days after Mr. Loynd started for the bags, and two days after he was last seen by his friends.

The young man in Reilly’s store said that Mr. Loynd had first gone into the store accompanied by Frank Reilly, a relative of the proprietor of the store who vouched that Mr. Loynd was all right. The young man added that Mr. Frank Reilly was a clerk in a bank, but said that he did not know the address. This statement is at variance with what Mr. Loynd told Mr. Bell. According to the latter, Mr. Loynd met the bank clerk on the ferryboat. According to the young man in the tea store, Mr. Loynd was accompanied by Mr. Reilly, who works in a bank, long before the ferry was reached.

The foregoing article appeared in the New York Sun this morning. The missing man, Mr. David Loynd, is not a clergyman and is not entitled to the prefix “Reverend.” He is a missionary and an evangelistic worker. When the Reverend R.V. Bingham was pastor of the People’s Baptist Church in this city, Mr. Loynd came to Newburgh, and for a time was associated with Mr. Bingham in the work of the parish. He visited among the church people and assisted in the various departments of the church work. He seemed thoroughly consecrated to Christian activity in all forms and was much beloved by all the people.

When Mr. Bingham, who was also an Englishman, left Newburgh to engage in mission work to Africa, Mr. Loynd accompanied him to Toronto, Canada. He returned to Newburgh later, and remained here for some time. The Reverend Eben Creighton succeeded Mr. Bingham to the pastorate of the People’s Baptist Church and Mr. Loynd assisted him for a time. He and Mr. Creighton were warm friends and Mr. Loynd was frequently a guest in Mr. Creighton’s home. He was always welcome among the people of the parish.

Early last year, Mr. Loynd returned to England and later engaged in missionary work in Africa.

Since Mr. Creighton retired from the pastorate of the People’s Baptist Church, he has been engaged in evangelistic work in Newburgh, and Mr. Loynd as coming here to help him. Mr. Loynd is a good vocalist and it had been arranged that Mr. Creighton should speak and Mr. Loynd sing at their meetings. On Sunday August 19, Mr. Creighton expected that Mr. Loynd would assist him at the services he conducted in the first Congregationalist Church and also at the service at the Y.M.C.A. building. He did not arrive, and Mr. Creighton was considerably disturbed until he received the following postal on Monday:

690 Eighth Avenue, New York City. 8 p.m. August 18. Dear Brother- Don’t worry about me as I have only been detained with my baggage. If I can get away on Monday, I will. Should I come to 16 Bridge Street and have my baggage expressed there? All well, yours faithfully, D.L.

Mr. Creighton also received the following postal which was written on Sunday and dated the 19th at 690 Eighth Avenue:

I came to the Alliance on Saturday to give in an order on some books and it got on towards evening. I had left my baggage in a wholesale store and on going for it to come to Newburgh as I thought, the store was closed, it being Saturday. And so the Lord cornered me here. Now I’ll wait for your reply. I have heard A.B. Simpson this morning in the Tabernacle: it’s quite a treat.

I was sick on board and hardly took any food at all, and so have been run down physically. All I desire is His will. When I reached Brooklyn on Friday afternoon, I found my old friend, a Baptist minister, had gone to Chicago and so I was somewhat disappointed. Still, I believe Romans 8-28.

David Loynd

Mr. Creighton went down to New York City on Tuesday morning to hunt up his friend. He had not arrived home this forenoon, but Mrs. Creighton expects him at any time.

Newburgh Daily Journal 8/30/1900

…the tea house referred to seems to be that of Mr. Robert H. Reilly, 38 Whitehall Street, and the young man Frank Reilly, a clerk in the American Exchange National Bank. Frank Reilly could not be found last evening, but a friend of his in his brother’s store said that a clerical looking man had left a handbag there several days ago but that he had taken it away last Friday. The young man said that Frank Reilly knew nothing about the Rev. Mr. Loynd and that he had not heard that Mr. Loynd had spent a night at Mr. Reilly’s home in Brooklyn.

Mr. Loynd was born in Bolton, Lancashire, England about thirty years ago.

New York Times 8/30/1900

Being a steerage passenger, he came through the Barge Office….

Frank Reilly, the bank detective, is equally mystified. The express man explains it all by guessing that Mr. Loynd became insane, but Reilly says he saw no signs of mental trouble during his brief acquaintance with the man.

New York Times. 8/31/1900

Missing David Loynd

Rev. Eben Creighton, who went to New York to search for David Loynd, did detective work on his own hook yesterday, and managed to find the missing evangelist’s trunk on the Cunard Steamship Line’s pier. He also learned that a man who gave the name David Loynd sailed for Europe on the steamer Servia a week ago last Tuesday. The Rev. Mr. Loynd was in the Christian Alliance Mission on Eighth Avenue the next day, Wednesday. Other persons who knew him say that he was seen in the city on Friday, two days later. His discovery convinced Mr. Creighton that the case was one in which the police should take some interest and he declared that night that he would go to Police Headquarters today and ask Capt. McClusky to detail Central Office detectives on it.

Mr. Creighton had not returned home up to noon today, but Mrs. Creighton received a letter from him this morning in which he communicated some facts about Mr. Loynd.

In his letter he said it seemed strange to him that Mr. Loynd should have called as late as last Friday at the wholesale warehouse for the traveling bags he had left there nearly a week before, when he was supposed to have disappeared on Tuesday of last week.

Mr. Creighton asked in the letter if any word had been received from Loynd’s relation in Cohoes to whom Mrs. Creighton had written a few days ago about his disappearance. Mrs. Creighton has not heard from these relatives and her letter has not come back from Cohoes.

Newburgh Daily News. 8/31/1900

Queer Case of Mr. Loynd

“Today I learned the address of the express office where his trunk order had been left. I went there and found that the trunk had been sent to the West Shore Station and had remained there for two days. As no one called for it, it was then sent to the Hudson Street office of the express company. Then, word came from an official at the Barge Office to send the trunk to the Cunard Line pier for shipment on the steamer Umbria for Europe.

Following up on this clue, I went to the office of the Cunard Line and there learned that a man who represented himself as David Loynd had engaged passage to England on Monday, Aug. 20, and had sailed on the Servia the following day. He left word that his trunk had been delayed and would not be at the pier in time to take it with him and requested that the trunk be forwarded to a place in England where Mr. Loynd would certainly not go- a place many miles from his English home.

The man in the tea store said that Mr. Loynd, the evangelist, called there on Friday and took away his valises. That was three days after a David Loynd sailed on the Servia. Now, who was the David Loynd who sailed on the Servia? I have had the trunk held on the Cunard pier, and it is there now. I think, though, it is time the police looked into this…”

Newburgh Daily Journal. 8/31/1900

The steamship people further say that their passenger gave his address somewhere in Derbyshire, England, but Mr. Creighton says Loynd never lived in Derbyshire, but Lancashire.

New York Times. 8/31/1900

The Missing Evangelist

The New York Sun had the following this morning relative to the disappearance of Mr. David Loynd, the singing evangelist for whom the Rev. Eben Creighton of this city is searching:

Chief Devery declared Friday that he wasn’t going to detail detectives to look for David Loynd, the singing evangelist who has been missing since August 21, because he, Devery, was satisfied that Mr. Loynd for some reason or other had decided to return to England and had gone back on the Servia without taking the trouble to say goodbye to his friends.

The Reverend Eben Creighton who came down from Newburgh to hunt for Mr. Loynd continued the search Friday but without result. He said he was more than ever convinced that the Loynd who sailed for England on the Servia on August 21 wasn’t the evangelist, but somebody who had impersonated him.

The clerk in Robert Reilly’s tea store at 38 Whitehall Street still sticks to his story that David Loynd called at the store two days after the Servia sailed. Mr. Creighton is very angry about what the police say about the case. He suggests that Loynd was lured away for thee purpose of robbery and declines to give up the search for him.

Mr. Creighton was in Newburgh today. He is inclined to look upon the bright side of the matter and is trying to hold to the theory that Mr. Loynd sailed Tuesday August 21, although there are many things that go against this theory. He has given up the search as he cannot do anything more. If Mr. Loynd sailed on the Servia he probably arrived in England on August 28.

Newburgh Daily Journal. 9/1/1900

And, with that, the press coverage ended. If Reverend Creighton wrote to David Loynd or his family in Bolton for an explanation, the response was not made available to the press.

The details surrounding the Reilly family, and their involvement with David Loynd, remain puzzling. One suspects that Mr. Loynd either fell victim to a confidence game, or a blackmail attempt surrounding the night he and Frank Reilly spent together, and fled the country at the first available opportunity. Reverend Creighton’s imposter theory, although possible, makes little sense since one can think of practically no gain in impersonating an impoverished evangelist.

Several bigamists traveling aboard the Lusitania saw their double lives exposed after the disaster.

The case of Maurice Medbury was one of the more intriguing, and acrimonious affairs to go public in the wake of the Lusitania. Medbury was a dealer specializing in antique jewellery and curios. He was making on average $10.000 a month by buying jewelry from impoverished European families and reselling them to American collectors. It was rumored that he was carrying $100,000 of jewelry with him on the final voyage.

Maurice Medbury had not seen his wife, Lora, for 10 years prior to the disaster. He had made payments of between $150 and $1,000 per month during that time. There had been no contact at all between the couple in the two years prior to the disaster. The Medbury family resided at 1622 Clinton Ave., Alameda, California, from the time they were abandoned.

Medbury sailed on the Lusitania on May 1, 1915, in cabin B101. His cabin steward was Thomas Dawes. Medbury was with passenger Isaac Lehmann in the smoking room, when the Lusitania was struck. Lehmann exclaimed, “They’ve got us at last! Let’s get outside!” Once on deck, Lehmann told Medbury to get away, as debris hit the deck and the roof of the Verandah Café. He did not see Medbury after that.

Initial letters of administration were refused by Judge Wells, in California, as there was no proof that Mr. Medbury had died in the disaster. Mrs Lora Medbury appointed attorney Milton Sheppardson to locate Mr. Medbury’s estate. Had Maurice’s body been recovered and identified, Lora Medbury made it clear that she did not want it buried anywhere near the family.

According to Lora Martin Medbury, the Medbury family fortune was built up from a $100,000 foundation, which had been left to her on the death of her father, a Utica, NY, business man. Sheppardson located $30,000 in a New York bank, $75,000 in a bank in St Louis Mo., and $75,000 in a Chicago bank. Accounts were also found in Berlin, Paris, Spain and Italy.

Rumors abounded that various women friends who Medbury acquired throughout his final ten years held property for him , but this was never proved. Then, it was discovered that there was a second Mrs. Medbury, in England. The English “wife” was a lady named Mrs. Maude Hare Danby Medbury, who lived with Maurice Medbury in Horsley, Surrey. If not legally married, they gave the impression that they were.

Researcher Zach Schwarz noted that in 1913 Mrs. Hare Danby, sailed on the Rotterdam for her yearly visit to her son in Texas. The next person below her on the manifest was Mr. Morris Wallace, a US citizen. Mr. Wallace’s place of birth, oddly enough, is exactly the same as Medbury’s! Apparently Mr. Medbury had an alias to go along with his shady double life

Probate reports in England showed that Medbury left no estate, suggesting that his property and financial assets may have been in the name of Mrs. Danbury Medbury. Given the fact that Medbury had two wives, the question was asked; did he die, or did he survive the disaster and then vanish, with the aim of starting a new life anonymously? The fact that several large bank accounts were left untouched points to the former, but given the cloudy state of his finances and his rather unconventional lifestyle, the latter cannot be ruled out.

Lora Medbury was awarded $7,500.00 as compensation by the Mixed Claims Commission, in Washington D.C. on January 7, 1925.

Third-class passenger, James Williams, was married in England in February 1902, and had one child. He deserted his wife and child in 1905, with his wife getting a separation order on March 14, 1906. Williams went with another woman to Canada, where he was imprisoned and deported as an undesirable person. He went to the United States in 1911, and married a woman who had a daughter from a previous relationship, on December 15, 1914, in Hoboken, New Jersey. His reasons for boarding the Lusitania are unknown; what is established is that he never divorced his first wife in England. He was lost in the disaster and his body never recovered.

One of the more compellingly bizarre scandals to surface in the wake of the Lusitania was that involving a figure from the past of Canadian passenger John Napier Fulton.

Mr. Fulton died in the sinking and his wife brought suit against Germany for $80,750.00. A settlement of $30,000.00 was almost finalized when the angry Mrs. Olympe Eugenie Chanteloup Geradin surfaced. It seems that Mr. Fulton had drained her late uncle’s estate of $300,000.00, and converted it into property while acting as liquidator. “The estate worth $300,000.00 was solvent when her uncle died and after Fulton got through with it her was not a cent left for her, the sole devisee.”

There was a court case following that revelation, which lasted from around 1894 onward. However, the case was deferred after Fulton was sentenced to 3 ½ years in prison, commencing in September 1900, for doing the same thing to a Mrs. Coristine, to the sum of $12,541.75.

Judgment was passed in 1922 that Mrs. Geradin was owed $120,143.02. The paperwork establishing proof of the other missing $180,000.00 had been lost in the 28 years since the beginning of the case. Things got ugly during the course of the trial, with Mrs Geradin’s lawyers revealing in court, with witnesses, that Fulton’s daughter was not legitimate. They established that he had fathered her with a local girl, in order to expedite a personal inheritance, which was conditional upon the birth of an heir.

Mrs. Geradin lost her case in the end, because there was nothing specific the claims court could do for her, and the property which her money had bought was placed in Mrs. Fulton’s name. With John Fulton dead, and no evidence present that Mrs. Fulton was party to the fraud, the property was untouchable. The Court however DID believe the story about the daughter being illegitimate and made it a point to say that they did not believe Mrs. Fulton on that detail.

The final score: Mrs Geradin: $0. Mrs. Fulton: $3750.00 (plus the income from Mrs. Geradin’s money, so she did alright in the end) Christian Fulton Fraser (the daughter): $6,000: “….whether he was her father or not, she was dependent on him and had much to expect from him by way of bringing up and education. With everything discredible that happened in his business he was an educated man of many good qualities, devoted to his family, who had the regard of influential friends to the last.”

Joseph and Evelyn Dredge

JOSEPH ALAN DREDGE 1872 – 1915 and EVELYN NORMAN DREDGE 1868 – 1915