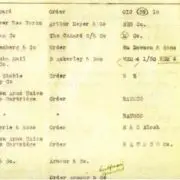

The Lusitania : Part 7 : Passengers of Distinction

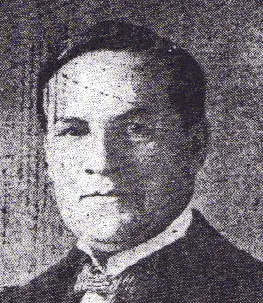

D. A. Thomas, father of Lady Mackworth and tablemate of Dorothy Connor, left this account:

Let me give you a consecutive narrative which I hope will assist the Government, the public and the Cunard Company to come to correct conclusions. I will avoid harrowing details as much as possible.

We got on board the Lusitania at nine a.m. on Saturday, May 1. She had been advertised to sail at ten: she actually left the Cunard pier at a little after twelve noon. We had seen in the press that morning an advertisement inserted, it was said on the authority of the German Embassy at Washington, notifying passengers sailing on British vessels that they did so at their own peril and that the German Government would accept no responsibility for anything that might happen to the passengers who disregard the notice after reaching the war zone. Curiously enough, this advertisement appeared in the New York Times in the column next to and in fact directly along side the advertisement of the sailing of the Lusitania that morning. There also appeared a statement by the representative of the Cunard Line pooh-poohing the threat, and giving an assurance to those sailing that the Lusitania would be well taken care of when she reached the danger zone.

Some of her passengers are stated to have received private intimation from German sources of the danger, but I received no such notice myself of any kind beyond what I saw in the press.

Well, I do not claim to be possessed of more than average courage, and I confess I felt some degree of nervousness when approaching the Irish coast, in fact, I determined to remain on deck with my daughter the whole of Friday night.

At the same time, after the assurances we had received and other information given apparently with official authority, and also after the statement that the Transylvania, a boat belonging, I believe to the Anchor Line, had been conveyed recently after reaching Ireland, I had no serious apprehension of the terrible disaster that afterwards occurred.

We had a smooth passage from New York. Only a couple of occasions did the sea become in the least bit rough. The weather was a bit foggy soon after leaving New York and again foggy shortly before reaching the Irish coast. The Lusitania hooted, and I remember remarking to a friend on board, “That gives our whereabouts away, but I suppose we are being well looked after.” That was on the Friday morning, when we were in the fog.

The fog lifted, the sea was particularly smooth, and the sun was shining very brightly without a cloud in the sky when we sighted the Irish coast about eleven o’clock. We appeared to be about fifteen miles off the Irish coast, sailing a course a good deal further away than on her outward trips when I had crossed before.

We left the luncheon table a little after two (ships time) and had barely reached the lift, there being a number of passengers about, when we heard the torpedo strike. It did not make any great noise where we were standing. I had always been led to believe that the Lusitania was unsinkable, and that it would take more than two torpedoes to finish her. We all realized immediately what had happened. I went up to ‘A’ deck to get more accurate information, and as we had previously arranged, my daughter at once went to her cabin to get her lifebelt.

All was quickly turmoil on the port side of the A deck. The boat soon began to list and I went down below to get my lifebelt. I did not succeed in reaching my cabin which was one of the parlour suites on the port side of B deck. I again went to A deck. By this time the steerage passengers had rushed up onto A deck, and they and others were crowded around the boats. There was absolute confusion everywhere, and an entire absence of anything in the way of discipline or organization.

I may say here that no attempt was made to close the port holes in the dining room deck.

I was told that the bulkheads had been closed, but in view of the very rapid submerging of the Lusitania I should require some strong evidence of this. I came quickly to the conclusion that my chance of getting into one of the boats was very remote. I, therefore remained away from the crowd, and a friend, meeting me and seeing I had no lifebelt, volunteered to go to his cabin and get me a blow-out belt.

We went together to his cabin and got it. I blew it up and put it on, and it did not give me any impression of security, as I felt it would at any moment collapse. I, therefore, determined to make another effort to get into my cabin. I succeeded, for the staircase and passages were quite clear. To my astonishment I found that the lifebelts I had left on the bed were gone! It appeared afterwards that one of the lifebelts had been taken up by my daughter to give to me, but she failed to find me, just as I failed to find her. The other lifebelt had been taken by someone.

I however, remembered that there were several in the wardrobes, and on opening these I found three. I put one on, and two of the Officers coming into the room at that moment I gave them one each. By this time the list on the ship had greatly increased, and, finding it difficult to walk up to the port side, I went to the starboard side on deck ‘B’, which by then was almost flush with the water.

Just opposite what was known as the grand staircase a boat had been lowered and was about three parts filled with people. It was about four or five feet away from the ship’s side, and was still held by the davits. There were a couple of women and a child opposite the boat. One of the women and the child jumped into the boat. The other woman became hysterical and screamed, “Let me jump, let me jump!” but was afraid to jump. I pushed her, and I made her jump, for I could not make my jump until I had seen her in the boat. Fortunately she reached the boat safely. I then put my foot on the ropes and made a jump well into the boat, which was then six or seven feet away from the ship’s side. On clearing the wreckage I helped to pick up two men and a girl, Miss Luny, who were clinging to the side.

We quickly cut ourselves away. Then another danger, which at the moment looked quite insurmountable, occurred. One of the huge funnels slowly descended towards the middle of the boat, and it did not look as if we had the smallest chance of escaping it. What happened then I can hardly say, but I shouted loudly to many nearest to me to push her away. This was done, and the funnel seemed to slide away from us as the ship went down. We were then between two funnels.

Though I believe I kept my feelings perfectly under control, I was suffering intense excitement and under such circumstances it is difficult to keep time accurately, but it could not have been more than fifteen minutes after she was first struck when the Lusitania went down bodily. I thought that it was inevitable that the suction would have brought us down, but it is a very remarkable thing to my mind that the sinking of the ship produced no effect at all on the steadiness of out boat, which then contained 50-60. It could not have held any more.

We at once moved away in a sort of way. As an old rowing man I tried to put a little organization into the business, but this was resented by two or three of the crew of the Lusitania who were with us, so I left it to them. The sea was absolutely calm; otherwise we should not have kept afloat for five minutes. The boat leaked, and we began to take in water. I helped to bail this out. It gained on us until it was up to our ankles. But after about twenty minutes bailing there was no more trouble in that direction.

We rowed in a sort of fashion for the coast, which appeared to be about fifteen miles away south west of Kinsale lighthouse, which was plainly visible in the sunshine. Soon we observed a little sailing vessel, and we made for her, going at the rate of a mile or so an hour. The smack was coming directly towards us but there was so little wind that her progress was also painfully slow.

By the way, before I forgot to say that I had set my watch to the ship’s time some little time after noon that day, and it pointed 2:25 immediately after the Lusitania sank.

We also saw the smoke of a steamer far away to the south, but after appearing to get nearer it went away again, evidently not having seen any of the boats. On clearing the wreckage I counted nineteen boats, some of them turned upside down and large pieces of wreckage with a number of people on each. In about an hour and a half, somewhere before four o’clock, a sailing boat came up to us and turned out to be the Wanderer P.L11 a Manx fishing boat of fifteen or sixteen tons. Captain William Bell, with a crew of four or five.

Captain Bell was an intelligent man. He took about 50 survivors off the boat, and about eight or ten of the crew, including two or three stewards, returned to the scene of the disaster in the boat. We, on the Wanderer, also moved in that direction, and picked up survivors on two other boats, casting the boats adrift. By this time the little smack could hold no more. We however took two more boats in tow.

A number of steamers were now coming up fast from several directions. The first one reaching the scene of the disaster about five minutes past five. We were some miles away but I could see that the steamers stood around in a circle with a diameter of several miles for some little time. Then I saw them all move in the direction of the scene of the disaster. We were then taken off by a tug called the Flying Fish and made for Queenstown, which we reached about 9.30 pm.

I had not seen or heard from my daughter since we parted at the foot of the staircase of the deck, she going for her lifebelt. I looked round for her for some time before going back for my lifebelt the second time but failed to see anything of her in the crowd and confusion. Also in my boat was my secretary Mr. Rhys-Evans. May I never suffer such agonies again. At about eleven o’clock the Steward, T. Godfrey of Seaforth, a gentleman who I am never likely to forget who had been waiting upon us on the Lusitania came up to me to say that Lady Mackworth was on a boat, the Bluebell, and she was safe but greatly exhausted. Captain Turner was also on the Bluebell.

David Alfred Thomas, Lord Rhondda, died in Wales, at age 62, on July 3, 1918. His daughter, Viscountess Margaret Mackworth, died in London on July 20, 1958, at the age of 75.