The Lusitania : Part 6 : The Port Boats

One enduring Lusitania myth is that of the chaos that reigned along her port side during her final eighteen minutes. Both historians and novelists have written of demoralized passengers, crewmembers struggling valiantly to push boats uphill against the worsening list, and of lifeboats crashing inward and tobogganing along the deck crushing and maiming those in their paths. And, such stories DO indeed appear in accounts written by survivors decades after the event. We were surprised, when we began collecting accounts written in the 1915-1917 time frame, to find very few references to anything resembling the popular version of the disasters alleged to have taken place along the port side.

May 1912 deckshot

Courtesy of Trevor Powell.

Passengers who stood on all points along the port boat deck, bridge to stern, survived to write detailed, and occasionally very angry, descriptions of the series of events that culminated with only a single boat, which barely survived, being successfully lowered before the ship sank. There is a consistency of detail among the personal letters and depositions of dozens of people who escaped from the port side. It is possible to determine from these that three lifeboats, and perhaps a fourth, were lost from the port side early on in the evacuation. An order was called down from the bridge to unload the already loaded boats, and crew members came along the deck and compelled the passengers to step back aboard the sinking ship. Several accounts make references to passengers being told “She is aground and will sink no further” and “She will not sink for an hour.”

Those offloaded from the boats stood and waited for additional orders that never came, as the ship listed, recovered, and began to heel again. Boat 14 was successfully lowered to the water in the last minutes, but was soon swamped and capsized. Some evidence indicates that a second port boat was lowered as the Lusitania began her final plunge, but was struck by the liner’s side and overturned as the ship sank beside it. First person accounts from 1915 show that passengers climbed back into the port boats at the last minute, without orders, probably hoping that they would break free from the ship as she went under. Yet, while the memories were still fresh and the anger still acute, none wrote of demoralized mobs or careening lifeboats.

“In regard to the launching of the boats, there appeared to be a complete lack of system,” said Norman Stones, of Vancouver, British Columbia, a few days after the disaster. “Near to us at the stern on the port side, no boat was launched except for one which fell into the water bow first. Officers and members of the crew went round saying that there was no immediate danger and that the ship would float for at least an hour. In consequence of this, a number of passengers made no effort to get lifebelts and were probably taken by surprise when the end came.”

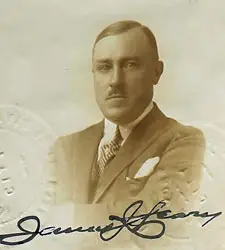

Norman Stones, and his wife, Hilda, were returning to Ilkley, Leeds, in May 1915, after receiving word that Mrs. Stones’ mother was in poor health. Mr. Stones, originally from Penistone, was a rancher and occasional nightclub singer in British Columbia. Hilda had been a successful actress and singer in Leeds before her marriage, with lead roles in stage productions like The Country Girl, and a position with a touring opera company. She was described as a jolly woman with an exceptional voice. She married Mr. Stones, in Vancouver, in 1912.

Friends in Leeds, where Norman and Mary Hilda were well remembered, initially hoped that the German warning might have caused them to defer their plans to cross.

Hilda Stones’ final performance was at a concert in second class the night before the disaster. Norman Stones did not mention which songs she sang, but it is almost certain that the young married woman with the beautiful voice, of whom Phoebe Amory wrote in her booklet, was Mrs. Stones. Mrs. Amory recalled that the young woman sang “The Rosary.”

Norman and Hilda Stones

We had just had lunch with the first sitting down, and had come upon deck. My wife and I were looking over the side from C Deck when I saw the track of a torpedo. It appeared to make a white, creamy, track apparently about six inches wide, and when I first saw it, it was between 200 and 300 yards from the ship. I saw no sign of a submarine, not a periscope or anything else. We watched the track of the torpedo as if fascinated, and saw it strike the ship between the funnels. We were second class passengers and were more or less confined to the stern of the ship. We were standing near to the railing dividing us from the saloon passengers, and would be at least 50 yards away from where the torpedo struck the ship. We heard the explosion and it was nothing very terrifying; we saw a cloud of spray thrown high into the air, and the next we knew was that water and wreckage were falling into the sea near us and on the decks above us. As we were not on the top deck, we were protected from the falling debris. The torpedo did not make a very big noise and did not shake the ship very much. All we felt was a slight tremor. The ship, however, immediately began to heel over to the starboard side, and so far as I know she never righted herself. I did not hear a second explosion like the first one, and am inclined to believe that only one torpedo was fired. The ship certainly gave an extra lurch shortly afterwards, but it appeared to me to be due to an internal explosion of the shifting of the cargo. At the time of the attack there were few passengers on deck, but immediately following the explosion there was a rush of passengers to the deck, and at first most of them crowded on to the port side, which was the highest out of the water.

My wife and I walked over to the port side. There was quite a lot of excitement, but no panic- no fighting or anything of that sort. The stewards were the best of the crew, in my opinion. They certainly did not show any panic; if any portion of the crew was inclined to be panicky or excited it was the firemen and trimmers who came up from below. The stewards went round quietly serving out lifebelts. In regard to the launching of the boats, there appeared to be a complete lack of system. Near to us at the stern on the port side, no boat was launched except for one which fell into the water bow first. Officers and members of the crew went round saying that there was no immediate danger and that the ship would float for at least an hour. In consequence of this, a number of passengers made no effort to get lifebelts and were probably taken by surprise when the end came.

Norman Stones obtained lifebelts for himself and Hilda. They planned on swarming down the ropes from the wrecked lifeboat, and then swimming clear of the ship. They hoped to find wreckage to cling to, or to be picked up by a boat. The Lusitania’s final plunge came so quickly that they barely had time to get over the side and into the water. Mrs. Stones took bank notes from her purse, and placed them into Norman’s pockets. She remained calm as she took hold of the rope, cleared the side of the ship, and jumped down into the water. It was the last time her husband would see her. Mr. Stones followed his wife into the water, and both were immediately drawn down as the Lusitania sank beside them.

Norman Stones recalled wreckage floating past him as he struggled to get clear of the suction. He came to the surface and was pulled under again. The second time he surfaced, the disturbance had subsided:

I never saw my wife again. There was no sign of the ship, but the water was full of drifting struggling bodies and wreckage. I got hold of a folded deck chair, and hung on to it for about half an hour, swimming and floating and looking for my wife. At the end of that time I drifted near an upturned boat, to the bottom of which about six men were clinging. I joined them, and we drifted about for hours until we were picked up by the stream trawler Indian Empire and taken to Queenstown. At the finish, we had about 20 persons clinging to the upturned boat.

Hilda Stones’ body was never recovered. Norman Stones’ initial reaction seems to have been anger. Phoebe Amory wrote that the husband of the young woman who sang at the concert promised, in her presence, to enlist and kill a lot of Germans. A 1915 news article preserves some of Norman’s observations, and is worthy of quoting:

Mr. Stones comments on the fact that although the trawler, only an eight knot boat, landed them in Queenstown only two hours after they were picked up, it was four hours after the accident before fast destroyers arrived on the scene. In that time a destroyer could have traveled a hundred miles, and rescued passengers were inclined to ask the reason for this delay. There is no doubt that the confident attitude of the officers and crew, and there statement that the ship would float for at least for an hour – excellent though the intention was- blinded passengers to the imminence of the danger. “We should have been over the side before if it had not been for that statement, and we probably should not have been sucked down with the ship” said Mr. Stones.

Norman Stones eventually remarried. He died in Exmoor, England, on September 7, 1964.

|

| Sarah Lund Courtesy of Joy Hill |

|

| Charley Lund Courtesy of Joy Hill |

|

| William Mounsey Courtesy of Joy Hill |

“Pa, I know it will sink!” said Sarah Lund, of Chicago, to her father, after they were ordered out of a port side lifeboat by a crew member who assured them that the ship would not sink.

Sarah, her husband, Charlie Lund, and her father, William Mounsey, were aboard the Lusitania on a mission that they hoped would reunite their family. The previous year, William Mounsey’s wife, Fanny, had set out aboard the Empress of Ireland to visit relatives in Keswick, England whom she had not seen in more than thirty years. She was aboard what proved to be the fatal voyage and was lost. Her body was not recovered and her family was left to grieve and to wonder. A woman by the name of Kate Fitzgerald then surfaced in an almshouse in Ormeskirk, England. She had an intense fear of water and kept muttering the name “Mounsey.” Word of Miss Fitzgerald reached the Lunds and Mr. Mounsey in the United States, and so they booked passage aboard the Lusitania hoping that, perhaps, a happy resolution to their family tragedy might be possible. It is known that they received at least one warning, from a Doctor Roberg, who pointed out that given the danger of a wartime crossing, it might be better to solve the mystery by letters and photographs. But, the group departed as scheduled.

Sarah and her acquaintance, Eunice Kinch, were on the starboard side of the Lusitaniawhen the explosions came: “We were sitting facing where it struck, and the minute it struck we were covered with water.” She ran to the lounge, in time to meet her father, and Mrs. Kinch’s son, William Mustoe, coming up the stairs. There was no sign of Charley Lund in the crowd. The group went to the port side boat deck where they entered a lifeboat, only to be ordered out by crewmen who said that the Lusitania would not sink. Sarah turned despairingly to her father and said, “Pa, I know it will sink.”

Robert Timmis, standing nearby, heard the order, and encountered Mr. Mounsey and Mrs. Lund after they evacuated the boat. Sarah pleaded, “Sir, I’ve no lifebelt” and Timmis removed his and strapped it on to her.

Sarah and her father spent their last minutes together struggling to climb a staircase, or perhaps a ladder, between the boat deck and the deck surrounding the funnels:

I found bits of remembered Sunday school lessons flitting through my head; I tried hard not to think of Mama. There was a big explosion, and down he went head first right in front of me, and the boat seemed to fly to pieces and I went right after him. We went whirling round and round. The sensation was awful. It seemed as if we would reach the bottom of the ocean. As I floated around in the water before being rescued, I could hear people calling and swimming; I heard a baby cry. I could feel people grabbing at my long hair and at my legs.

Sarah clung to a board for what seemed like hours before being pulled into a lifeboat. There she met Robert Timmis, who had surrendered his lifebelt to her, and he bent down to shake her hand as she lay cold and exhausted in the bottom of the boat. Timmis later described Sarah’s rescue: There was a woman further on I thought might be alive; she was face down with a belt on, but seemed shoulders high out of the water. Her golden hair which was loose over her shoulders showed up well…

Neither William Mounsey nor Charley Lund survived the disaster. Their shipboard friends Eunice Kinch and William Mustoe were lost as well. Only Charley Lund’s body was recovered. Sarah completed her trip alone and, to compound the misery of her experience, the trip proved to have been needless. Kate Fitzgerald was not her mother:

I have only one thing to regret and that is to have to part with my husband and father. My husband and I were very much devoted to each other and it is a terrible blow to me to be in England so far from home and such a bereavement to bear, I feel I could not stand it if Almighty God was not with me to bear all my sorrow.

Sarah returned to the United States where, in October 1915, she initiated a lawsuit against Cunard. She alleged that there was a large cargo of explosives illegally in the hold. She sued for $40,000 and said that Cunard’s statements that the Lusitania was fully provided with safety devices had deceived her. She married George Hornberger, whose job was to investigate Lusitania claimants, in August 1916, Someone familiar with the details of Sarah’s case notified Cunard that she had married a man with a German surname and advised that the newly married couple be closely watched. Her suit against Cunard was futile, but she was awarded $5,000.00 by the American Mixed Claims Commission, in 1925, for the loss of her husband and personal injury, and an additional $288 for lost property.

Sarah Lund Hornberger had no children of her own, but she proved to be a favorite aunt within her extended family and is still fondly remembered. She died at the age of 92, on April 2, 1978, in Niles, Illinois.

A bathroom steward that had given me a bath in the morning came aft, a big fat fellow with a lifebelt on, and he called out, “Everybody out of the lifeboats. We are hard aground we are not going to sink.” We got out… I think that if the Cunard Line had practiced the manning and getting away of the boats and the proper assignment of officers and crew to the lifeboats the loss could not possibly have been one third of what it was. It is nonsense to say there was no confusion. There was panic. There was no discipline at all. Worst discipline I ever saw.

So concluded Joseph Myers, one of the most seriously injured Lusitania survivors. Mr. Myers was one of several passengers to climb into a port side lifeboat as the ship began her final plunge. The extent of his injuries demonstrate the extremely violent dynamics of the sinking, and why so few who attempted this means of evacuation lived to tell about it.

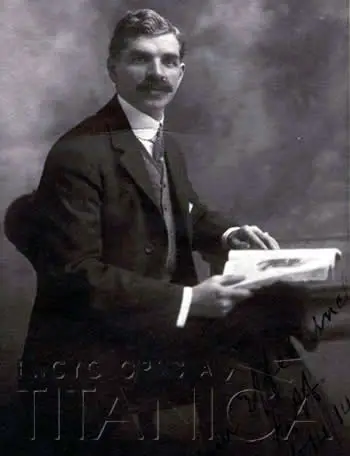

Joseph Myers

Myers was a lace manufacturer from New York City, whose business concerns in Europe assured that he was a frequent transatlantic passenger. He had made over 100 round trips during the course of his career, and consequently had a better understanding of how ships operate than most passengers on board the final voyage. Myers had transferred to the Lusitania from the American Line’s St. Paul, believing that he would save at least a day’s travel time by taking the faster liner. He realized, while aboard, that the Lusitania was traveling at reduced speed and would never make port by Friday, May 7, as he had hoped.

Myers found much to criticize about the final crossing. Describing the swinging out of the lifeboats on Thursday, he said:

The men were not efficient. I saw them trying to throw out the boats, trying to break away the boats from the davits, and it seemed to me that they were not equal to it. They were clumsy in handling the ropes. They were bossed by some petty officer; I don’t know who it was, but the men did not look to me as if they had been handling the boats before. They handled the ropes and falls like men building a house; they looked more like day laborers than seamen.

I could see it [the Irish Coast] very plainly, very plainly. I should imagine that before luncheon we must have been 10 or 12 miles away and gradually got closer to the coast. I could see very clearly the coast, and could see also, I believed, the lighthouse. Afterwards I found out that it was the Kinsale lighthouse…….it was as near as we had ever gone; I don’t believe to my recollection that I ever passed very much closer to the coast, excepting once and then we went inside Fastnet. My impression was that we were nearing the coast considerably, just as if we were going to make port.

Myers took his luncheon with Francis Kellett of Tuckahoe, New York, after which both men went on deck in time to witness the sequence of events leading up to the torpedoing:

I was standing there with Mr. Kellett. We were standing there discussing the conversation we had had at lunch with another party. I happened to see a periscope and called attention to that periscope to Mr. Kellett.

Q. What did that periscope look like?

A. Like a periscope.

Q. Had you ever seen a periscope before?

A. I had.

Q. How did you happen to see them before?

A. I had been chased by submarines crossing the channel. It looked like a chimney. It was not very large. It was very small; it stuck right up out of the water like my hand, perhaps three feet. At the time I first saw it and called Mr. Kellett’s attention to it was just about in line with the captain’s bridge. I said “My God, Frank, there is a periscope” and I pointed it out to him. By that time the vessel had proceeded and the periscope remained stationary. I said “My God, Frank, they have put off a torpedo. My God, Frank, we are lost” and she struck. There was water and coal dust and debris of all kinds blown up; they came through the funnel and up through the side of the boat, alongside the boat rather. I went into the Verandah Café to avoid the debris which was falling aft., I didn’t avoid it all.

Francis Kellet

I went forward, and going along into a companionway of some sort, Mr. Kellett and myself. I went forward and he went aft to obtain life preservers, because I stated to him that we would never attempt to go below. I feared very much that we would never come up if we did go below…he seemed to have been the lucky one in finding the lifebelts. I tried two or three stewards lockers and tried to see if there was a room that had a lifebelt in it, but I was not successful forward. Mr. Kellett went aft and called to me, stating that he had one for me. I came to him and adjusted his lifebelt on him, and he helped me with mine. We got them on wrong. It was very singular that we should, because they had plenty of printed notices how to put on a lifebelt in each room…I had never thought of putting on a lifebelt, and never anticipated any trouble on the Lusitania. I never heard anything about the warning or anything of the kind…

There was great confusion and lots of excitement. Everybody was pouring up through the companionway. The second class was coming up from their quarters trying to get on our deck, and they succeeded, and finally one of these passengers came up with a boy and asked if I wouldn’t help her into one of the lifeboats. I assisted her in, and assisted her boy in, and she begged me to come in the boat with her, because at that time there were very few men in that boat. She said ,“We really will require some men; for God’s sake come in and help me with my boy. Please don’t let this boy drown.”

Mr. Kellett and I finally decided to get in that boat with these passengers and we stayed with that boat. There was nobody there to lower it…You had to get into that boat over the collapsible boat; there was a collapsible boat attached to the deck, and we climbed over it to get into this lifeboat that was swung out….She had plenty of room to go down if there was anybody there to lower her. A bathroom steward that had given me a bath in the morning came aft, a big fat fellow with a lifebelt on, and he called out, “Everybody out of the lifeboats. We are hard aground we are not going to sink.” We got out.

I was becoming a bit uncomfortable on account of the crowd that was coming up from all over. They were coming from the bow and the stern and crowding up around us, and I said to Mr. Kellett, “Frank, the best thing we can do is get into this boat again and wait until she goes over.” … I did get back into this boat and waited for the big boat to go down, and I thought this would be the safest place to be thrown away from, but it was so aft that when she did go down we were thrown out. ..There were ropes around my body and I was being dragged down. I sat up in the bow of this lifeboat, underneath the davit. The block and tackle were right above me…and the ropes happened to be underneath me, and what happened I don’t know, except that these ropes were around my body and dragging me down. I couldn’t do very much because I had my ribs broken and my leg broken and my arm very badly hurt. I laid in the water, and finally there was an overturned lifeboat coming pretty close to me, and I managed with my left hand to work my way over to this boat and hang on.

Joseph Myers was rescued by the Katrina later that evening, and brought into Queenstown. Francis Kellett was lost, and his body never recovered. Myers wrote his mother a lengthy account of the disaster while in Queenstown, which corresponds to his 1917 testimony and contains a more personal look at his experience than he allowed himself to give at the Limitation of Liability hearings:

The Golding Nursing Home Cork, Ireland May 22, 1915

My Dear Mama: Marie wrote to you last week and I can now do so, although I am in bed and have been so for two weeks on my back. Oh, how it hurts. Well, I suppose you want to know what is the matter with me. My right leg is broken, my left leg is torn, the nerves all exposed under the thigh, three ribs broken front and back on the left side and two on the right, my right arm badly torn. This all happened after the second explosion- I am sure we were torpedoed twice. I saw the first leave the submarine and saw the submarine dive and saw the torpedo strike us and saw everything else. My God, what a sight. In twenty minutes we were gone. I went down with the ship. How long I remained down I don’t know, but it was while I was under water that I so badly got knocked about. Wreckage bumped me up against the ship under water and I fought like a devil. The face of my dear wife and our little boy was before me and I said to myself over and over again, ‘I can’t go. I must fight this out and win out for their sake.’ and that is what gave me strength and courage.

Well, I was four hours in the water swimming and floating about with a broken leg and ribs, but not until I was pulled on a boat did I feel that I was hurt. They thought I was about gone. They took all my clothes off and rolled me about until I cried for help and mercy, then they found that I was injured, threw me into the engine room and left me there without anything on. We arrived in Queenstown the next morning at 2:30, just twelve hours after we went down. They put me in a naval hospital, where I remained until Sunday evening and was then transferred here without any clothes and now am on the road to recovery.

Not until Monday did the Cunard Company report me as saved, although I sent them my name on Saturday at 3 A.M., but their office in Queenstown can only be compared with the confusion on the Lusitania. When we were struck, all the officers lost their heads, boats could not be launched. Only two got away safe, all the rest were lost. Those four hours in the water, I shall never forget. I saw my friends and acquaintances float by dead or almost so and I could not tender any help; I was too weak; it almost drove me mad. Thank God it was such a fine day and the water so warm. I had on a lifebelt and can swim and float. At 6:30 P.M. I was pulled on a Greek steamer which picked up fifty-two survivors and I was the last one saved.

Your loving son,

Joseph L. Myers

Palpable anger emanates from the letter survivor May Maycock, 23, wrote to the mother of missing passenger Richard Preston Prichard. Miss Maycock, who was returning to Buxton, England, after spending several years in Harrison, New York, assured Mrs. Prichard that the men behaved wonderfully, and then corrected herself by adding that she referred only to the male passengers. Miss Maycock had been loaded into a port side boat, and then was ordered out by crew despite protestations. The passengers stood and waited for the order to re-enter the lifeboat until the ship sank under them, and she was washed over the rail.

Palpable anger emanates from the letter survivor May Maycock, 23, wrote to the mother of missing passenger Richard Preston Prichard. Miss Maycock, who was returning to Buxton, England, after spending several years in Harrison, New York, assured Mrs. Prichard that the men behaved wonderfully, and then corrected herself by adding that she referred only to the male passengers. Miss Maycock had been loaded into a port side boat, and then was ordered out by crew despite protestations. The passengers stood and waited for the order to re-enter the lifeboat until the ship sank under them, and she was washed over the rail.

A second letter, made available to the newspapers, was less critical:

It is the greatest miracle in the world that I am here. I was just finishing writing to you when the vessel was struck. It was impossible for me to get a lifebelt as she began to list right away, and there would have been no hope of my getting up again. I managed to get out on the top deck and get in a lifeboat, but as soon as we were all in, some of the crew came along and told us to get out as the ship had settled and would be towed to Liverpool. However, we had no sooner got out than there was another explosion.

It was impossible for me to get in the boat a second time so I climbed up to the top deck of all and clung to the rail. I was right by the funnels when the engines burst. I hung on until I should think I was almost the last one. Then, as the boat was sinking, I had to let go or be pulled down with her. It seemed I was under water for an eternity, although I suppose it was only for a few minutes, I felt around and managed to get hold of a piece of wood about as big as myself. I got on top of this and lay flat on it. I floated about in this way, with no lifebelt, for about four hours, and was picked up about 6 o’clock by the Indian Empire, reaching Queenstown about 9.30.

The people I was most intimate with on board were picked up by the same rescue boat. It was a happy meeting, and we all came here together and were accommodated in the same room. They had great difficulty finding room for us all. It was wonderful the way we met, as I never saw them while the boat was sinking or while I was on the water. The crew of the Indian Empire were most kind, doing all they could for us. You would have laughed any other time if you had seen us sitting round a big can of tea, with a chunk of corned beef in one hand and a ship’s biscuit in the other. I guess I have come through a lot luckier than some. There was no panic on board.

Robert Dyer, of Pittsburgh, was in the process of entering a port side boat, when a boatswain came along:

“Go easy” he said, “the bulkheads are alright.” All the same, I got up along the deck and climbed a piece up the mast…then the ship sank, and I sank with her. It seemed that I was below water for an hour, but I got clear of the rigging and the wreckage around me at last, and floated away up to the surface. Finally I swam to an upturned lifeboat. The thing that troubled me was the poor women and helpless children drowned without a chance for their lives.

Fred Gauntlett, Samuel Knox, and Albert Lloyd Hopkins were in the dining room when the torpedo struck. Mr. Gauntlett was a long time employee of the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, of which Mr. Hopkins was the president. They were en route to England:

For the purpose of trying to make arrangements with the builders of a certain submarine, with a view to building them legally in this country; we were going largely at the insistence of the Secretary of the Navy.

Samuel Knox

Gauntlett left an excellent eyewitness statement, including details of the loss of boat 20 on the port side:

…I stayed behind, calling to the stewards to close the ports, which call I repeated several times, but without effect for as far as I could see no port was closed. I then left the dining saloon and made my way to the boats on A deck, and left the companionway on the port side, which was the high side of the vessel, she having taken a very heavy list to starboard by this time…

Frederic Gauntlett

One of the lifeboats was about full of people, mostly men, and two of the crew were about to lower away. I watched the lifeboat going down, when the man handling the forward falls lost control and the boat was dropped into the water, a distance of about fifty feet. The forward end being so much lower than the after end that people were thrown either out of the boat altogether or into a struggling heap at the low or forward end. The boat was smashed and everyone thrown into the water.

I then helped to line up and put into the next boat a lot of women and children, and becoming convinced that the vessel was doomed to sink, decided to take a look at things from the starboard side. The starboard side had been comparatively deserted, and I walked forward and saw that the bow was under water and the vessel’s starboard side very near the water. Decided it was time to get my life belt.

I then went to my stateroom and found my belt on the lower berth, the other one having been taken. From this I concluded that Mr. Hopkins, who shared my room, had already been there and secured his belt. l had not seen him since he left the dining saloon, nor have I seen him yet.

I then went up to A deck again on the starboard side and by this time B deck was under water. And in a minute at most, the boat deck or A deck was submerged in the final roll of the vessel. I slid down the deck and grabbed a boat davit to save myself from being thrown into the water…climbing on the rail, I swung myself by the fall from the deck of the Lusitania into a boat that was empty of people and which no one had attempted to lower away. A woman and a man with a baby were thrown into the water, and these I pulled into the boat, but the boat davits immediately came over on the boat and carried it down with the Lusitania leaving me in the sea.

I turned round and saw one of the funnels apparently coming right down on top of me and swam as fast as possible out of the way of it. I was then caught across the back by one of the antennae of the wireless, and turned over and grabbing the wire with my hands pushed myself away from it.

I then took hold of an air tank, probably from one of the lifeboats that had been smashed, and looked around to see if there was not some more secure wreckage to which I could hang on until relief reached me. I saw one of the collapsible lifeboats, canvas cover still on, a short distance from me and swam to it.

Gauntlett was the first to reach the collapsible, but was soon joined by other survivors. When they attempted to get their craft into working order, they discovered that it was in poor condition:

…the working parts were so stiff or rusted we found it impossible to do this [By this, Gauntlett meant rig up the sides] and some of the parts were broken which made it impossible to raise the sides and seats so that they would stay up. We then picked up wreckage and put it under the seats to prevent them from collapsing, rigging out the oars, and rowed around picking people until we numbered thirty two in all. Mr. Knox was the last person but one we picked up.

Gauntlett, Knox, and the rest were picked up by a fishing boat, which rescued the occupants of two other lifeboats for a total of at least 100 rescued. They were transferred to the paddle vessel Flying Fish, and brought in to Queenstown by 9:30.

Mr. Gauntlett became the Washington representative of Newport News Shipbuilding after he returned to the United States. He died in Chevy Chase, Maryland, at 81 years old, on August 9, 1951.

Ogden and Mary Hammond, of New York City and Bernardsville, New Jersey, were passengers of Boat 20; the first port side boat to be wrecked in launching. Mary Picton Stevens Hammond was probably the wealthiest woman aboard; her personal assets, independent of her husband’s fortune and their shared properties, totaled more than two and a half million dollars. She was descended from two prominent “old families,” and was a woman of great beauty and determination.

Mary Hammond

Ogden Hammond’s reaction to his wife’s decision to travel to Europe in order to do war-related charitable work has not survived. However, his reluctance to sail aboard the Lusitania is well documented. He attempted to enlist Cunard’s NYC general manager, a personal friend, as an ally in his efforts to get Mary to alter her plans. He testified that the scheme did not work as hoped: I asked him if he thought it was perfectly safe to go over on the Lusitania, and I remember his statement was, “Perfectly safe; safer than the trolley cars in New York City.” They booked passage on April 26, 1915, and occupied cabin D20, for which they paid $524.

Mary Hammond’s descendents claimed, in a recent biography of her famous daughter, U.S. Congresswoman Millicent Fenwick, that a German official relayed a message to Mary though her aunt. Mrs. Hammond was warned not to sail on the May 1st voyage. Her response was, “We are sailing on the Lusitania.” Her family made a final attempt to persuade her to change her booking, but the Hammonds sailed as planned.

Mary altered her will aboard the ship, before she sailed, protecting the inheritance of her children; Mary, Millicent, and Ogden Hammond junior, all of whom who remained behind in Bernardsville, New Jersey, in care of their governess.

The voyage would mark a milestone for Mr. and Mrs. Hammond; May 7, 1915 was their eighth anniversary.

Ogden Hammond returned to New York alone. He testified:

I was in the lounge on A Deck. The blow felt like a blow from a great hammer striking the ship; it seemed to be well forward on the starboard side. We were then at the time with Lady Allan of Montreal with her two daughters and Mr. Orr-Lewis. I took Mrs. Hammond and Gwendolyn Allan, and Mr. Lewis took Lady Allan and Anna Allan. We found no life preservers and could not get any. In a minute or two Lady Allan’s maid came with two life preservers for her, and Mr. Lewis’ valet came with one for him, which he gave to one of the Allan girls. Mrs. Hammond and I then started back on the deck looking for life preservers. We could not find any.

My wife and I went out on deck and there was a good deal of confusion. We looked for life preservers, naturally; I couldn’t find any. I wanted to go down to my stateroom and get my own, but she did not want me to leave her, so I stayed with her, and we walked back to the end of the A deck, and as we got to the end of the deck and found no life preservers we noticed them beginning to lower the end boat on the port side. We were told to get in. A petty officer, I should say, standing by the lifeboat, said “Get in,” and everybody at first held back. Finally I should say ten women got in. My wife refused to go without me, and we waited and waited and finally I agreed to get in, and I think I was the last man in, right up near the bow of the boat. The boat was half filled, about 35 people in it. They started to lower the boat, and the man at the bow let the tackle slip, and I remember I grabbed it and that it pulled all the skin off my right hand. The bow dropped, the stern tackle held, and everybody fell out of that boat from the top deck, which I think is about 60 feet above the water.

I finally came up and someone grabbed me around the neck, as I remember, by my necktie, and I finally got rid of the man and I got an oar. When I got my breath back and recovered myself I floated on this oar back out into the channel, and from there lying out in the channel I watched the Lusitania go down, probably about three-quarters of a mile away from me at that time. Well, in addition to my hand, I had a broken rib that I found afterwards. When I got to Dublin I found it, and my neck was badly hurt, probably in the fall.

Mary Hammond was never found, but a body matching her general description closely enough to be interesting, appeared in the 1916 Cunard Confidential Report’s list of unidentified dead:

#101. Female, 34 years, dark hair, slight make, height 5’4″ Property- 1 gold curb padlock bracelet; 1 9 carat square locket (engraved); 1 22 carat gold wedding ring; 1 18 carat gold plain ring, with heart; 1 9 carat signet ring with initials “M.H.” and 1 9 carat gold necklet. Buried Queenstown, May 10th; Grave C, 6th row, upper tier.

However, a direct quote from Ogden, dating from late May 1915 implies that he did at least some searching in the Queenstown morgues, and probably viewed #101: I examined a number of watches which were taken from drowned passengers and many of them had stopped between 2:30 and 2:35 PM.

Ogden Hammond, who remarried, served as U.S. Ambassador to Spain. He died in 1956.

Andrew Faulds, of Yonkers, New York, was hospitalized in Queenstown for several days after the disaster. He was injured when he was thrown from a collapsing Lusitania lifeboat. His survival, and that of his wife, was among the more miraculous of that afternoon.

Mr. and Mrs. Faulds were aboard the Lusitania en route to their native Scotland, where they intended on visiting Mrs. Faulds’ sister, Mrs. William Peacock of Glasgow. They wrote to Andrew’s mother, Mrs. Margaret Faulds, after the disaster, to assure her of their safety. Their first person account has not survived, but Mrs. Faulds allowed the Yonkers press access to the original letter:

They said they never heard a word about the threatened torpedoing of the vessel before they went on board at New York. When the torpedo struck, Mr. Faulds was lying in his bunk, and Mrs. Faulds was on her way up to the deck. Mrs. Faulds rushed back and told her husband to hurry up, as something had happened. They left the cabin without any thought of lifebelts, or anything else. Mr. and Mrs. Faulds had to fight their way through a crushing mass of passengers. A gentleman handed Mrs. Faulds his lifebelt, but Mr. Faulds was still without one. Both scrambled into a boat that was being lowered into the water, but suddenly one of the ropes gave way and the entire occupants were precipitated into the water, a distance of about 40 feet. Mrs. Faulds was in the water two and a half hours, and Mr. Faulds for three hours before being rescued by different steamers. Four times they got into a boat which capsized through filling up with water, and it was when the boat capsized on the fourth occasion that the two got separated. Mrs. Faulds floating way and ultimately being pulled on to the bottom of an overturned boat by a steward. Among the many pathetic scenes witnessed by Mr. and Mrs. Faulds was that of a young woman who was observed holding a dead baby close to her breast. Latterly, the woman lost consciousness and the body of the child slipped from her grasp and floated away on the water.

Andrew Faulds died in Yonkers, New York, on March 30, 1942, at age 55. His wife, Margaret died in Florida on May 8, 1968, at age 80.

The woman with the baby who Mr. and Mrs. Faulds witnessed as they struggled by the capsized boat, coincides with a detail in an account given a survivor from #14, the only boat known to have repeatedly capsized.

(Jim Kalafus collection)

Annie Sharp was returning to the United Kingdom from Boston in May, 1915. She was one of perhaps 60 people lowered from the port side in Boat 14.

The lifeboat was not properly plugged and began to fill with water. A woman bailed it out with her handbag.

I did not have a handbag and felt helpless. One man wearing a pork pie hat wasn’t doing anything with it, so I took his hat off and began to bail with it.

Boat 14 soon overturned, and Mrs. Sharp found herself struggling in the water, surrounded by its other occupants. Most of them managed to climb aboard again, but the lifeboat soon overturned for a second time. And a third.

During one of the capsizes, Annie Sharp found herself struggling beside a family who had been in the boat. The mother and father were lost, and she found their infant thrust into her arms:

I looked at the baby after, and I was sure it was dead. Its eyes were all glassy. Another wave threw us over and I went under with the baby. That was the last I saw of it. I must have been under the water a long time. The men got back on and I hear them talking. I heard one say “Good God, she’s alive.”

Boat 14 capsized several times that afternoon; Annie Sharp would remember six. Only a handful of the original sixty occupants remained, by the time the survivors were taken off by another boat. Mrs. Sharp lived in England until the mid-1960s, at which point she moved to Canada to live with a married daughter.

|

| James Leary |

|

| Leary and King Cabins (B-14 King, B-16 Leary) (Courtesy of Paul Latimer) |

|

| Lusitania’s Elevators (Scientific American) |

|

| The coffins of victims Thomas Boyce King and Lily Lockwood, photographed in Queenstown. King would be returned to the United States, while Lockwood, a child who was lost along with her mother, Florrie; brother, Clifford; and aunt, Edith Robshaw , was buried in one of the common graves. |

|

| Grave of Thomas Boyce King Greenwood Union Cemetery, Rye New York. |

We were standing right below the captain’s bridge, and Staff Captain Anderson was standing on this little bridge and he was shouting instructions to the different seamen; so I remember he hollered “lower no more boats. We have closed certain bulkheads in the ship and she won’t sink, and we can get into port.”… As it was going down, this lifeboat that was in front of us that the people got out of after the captain had given instructions, and though some insane idea I had I jumped in, and she was tied there, and that was the way I went down.

James J. Leary, of Brooklyn was a buyer for Brokaw Brothers. He embarked on the Lusitania with his friend, and fellow Brokaw employee, Thomas Boyce King, and survived to give graphic testimony about his Lusitania experiences.

Leary and King, in common with most of their fellow travelers, did not learn of the German warning until they were aboard the ship. Details of how they spent their time aboard the Lusitania are few, and with the exception of Leary winning the ship’s mileage pool, it seems that their voyage was pleasantly unexceptional.

Leary spent the final morning walking on deck after having breakfasted in his B deck cabin. He observed that the Irish Coast was clearly visible. He also noted that the Lusitania was traveling at a very slow rate, a fact on which nearly all of the surviving passengers agreed:

They had a drill one morning, about 10 or 12 men out on the starboard side. Mr. King passed the remark to me “How would you like to take your chances with that crowd in case we are torpedoed?”

Mr. King and myself went down to the dining room and we had out lunch; it was his custom to leave right after lunch to go and take some medicine, and I went to a table with Mr. Campbell, Mr. Battersea [sic: Battersby] and Mr. Hardwick….that was right inside the dining room three tables from the entrance. We conversed a little while and then we started out to the deck, and just got out the threshold of the doorway when we got the explosion of the torpedo. It sounded to me like a terrific explosion like what you would hear in an excavation in the subway. I went up top C deck, and the stairway was quite crowded, and then I went over to the side of the ship, to look out, to try to find where the torpedo hit. I saw this tremendous hole, and I saw the people jumping off and lowering the lifeboat, which seemed evidently cut away from the side of the ship, and this boat was filled with passengers and they were all thrown in the sea, and the boat swung in the air on one rope.

The lurid tale of first class passengers trapped in the ship’s elevator cages and sinking with the ship has become an integral part of the Lusitania legend. Although it surely could have happened, the earliest account of this aspect of the tragedy we have found is contained in Leary’s flamboyant testimony:

When I came from this entrance where I went out to look at the hole in the side of the ship, I looked at the ventilators (elevators) and looked up and noticed that they were between the two floors, filled with passengers screaming, and evidently they could not go up or down because the boat was on such a list, and I imagine that is the way they died.

The next paragraph must be viewed with skepticism. Recall this passage when reading Leary’s 1915 account, which follows:

I started to look in the different rooms for a lifebelt; they were all gone. My room was so far forward and the boat was on such a list that I thought it would be impossible for me to get to it, so as I went along I saw an officer coming along with a lifebelt in his hand…everybody was running around and screaming and looking for a belt; so I saw him I met him in the companion (way) going towards this room and I was trying to get the lifebelt. I had exhausted every place and could not get a belt, and saw him with one in his hand. I asked him for it, and he said “you will have to go and get one for yourself; this is mine.” I said “I thought according to law passengers come first.” He said “Passengers be damned; save yourself first.” I tore it away from him, and I said “you can find one quicker than I can, and if you want this one you will have to kill me to get it.”

Pressed to identify this officer, Leary could not. Nor could he give a detailed description, and even his general description was vague. The event may have happened as Leary said it did, but it seems likely that the man in question was simply a member of the crew.

I went up to A deck to look for Mr. King. I said to him “Well, Tom, we finally got it.” And he said “Yes, I knew it all the way over.” I started to put my belt on and got it upside down and this chap came along and said “if you got in the water that way you would be feet up.” So he put it on for me. You are supposed to put it on like a vest, and I put my hands in it. There is a collar that fits in the back of the neck and I had it on front.

We were standing right below the captain’s bridge, and Staff Captain Anderson was standing on this little bridge and he was shouting instructions to the different seamen; so I remember he hollered “lower no more boats. We have closed certain bulkheads in the ship and she won’t sink, and we can get into port.”

I met McCubbin the purser. I had all my valuables in the safe with him, and I said “how about my valuables” and he said “young man. If we get to port you will get them, and if we sink you won’t need them.”

I met Mr. King again. And we stood there, and there was a lifeboat in front of us and we had to lean up against the wall on account of the boat being on such a list……I said “I think we had better take our chances on deck” so we did not try for the lifeboat. Then just a few minutes after the was another explosion that seemed to me like the boilers. Of course all the soot and coal dust and different things came through the ship, and everybody got covered with it, and then she took a plunge.

As it was going down, this lifeboat that was in front of us that the people got out of after the captain had given instructions, and though some insane idea I had I jumped in, and she was tied there, and that was the way I went down. As the boat went under water something caught on my leg; I think it was the oars that criss-crossed and held me fast, and it seemed to me I went down as far as the ship did. There was a terrible drag from this thing holding me, and she seemed to settle more then and I kicked myself free and came up.

I saw an upturned lifeboat and swam to it and hung on to it by my fingers. There happened to be three or four stokers or seamen hanging on with me. We were 20 in all, and we decided to turn her over, and we got on our stomachs and turned it over, and when we got it turned over she was covered in canvas and ropes all through different parts, so it was impossible to take the covering off. So we stood on that and a wave would come along and we would go over, and would be pulled back, and we did that for half an hour. Every once in a while we would miss one or two, and the bodies would float around, and we would push them away when they were dead. We went on for four and a half hours before we were picked up by a British destroyer. There were only six of us left in the end.

Leary’s 1917 testimony is extremely dramatic, and one suspects that a degree of grandstanding occurred as he spoke. His 1915 account tells essentially the same story, but in a considerably more spare manner, bereft of lurid details such as the passengers trapped in the elevators, the interlude with the officer refusing to part with his lifejacket, and the hole in the side being visible:

At lunch on Thursday the lifeboats were swung out. That night all lights were extinguished or observed. A Mr. Winters who was connected with the Cunard Company said that morning wireless messages had been received and that there would be no more lights allowed at night. From about 1:30 AM to 2:30 AM on Friday I was on deck and saw a light some distance away a beam which gradually disappeared as we left it behind. I was berthed on B deck (Leary was in B-16) and found a blotter placed over my skylight that night to obscure the light. I dressed and came on deck on Friday at about 12:30 PM. I left the luncheon table at about 2PM and was just outside the dining room door when I heard an explosion, and felt a very heavy shock after which all the lights went out. Everyone hastened up on deck; there was no panic.

The torpedo struck on the right hand side; the rails and deck were a mass of wreckage about amidships. The crew lowered the life boats; women and children only were allowed in them. I didn’t realize the danger and went to my stateroom for a life preserver, but couldn’t get one in the dark. I searched for two but couldn’t find any so got one from a member of the crew. I then found Mr. King, Thos. B. on A deck and said to him that “we’d got it” meaning that we’d been struck by a torpedo. He assented calmly; there seemed to be no excitement. The staff captain announced from the bridge “lower no more boats” and said that he could reach port before the vessel sank. Officers and crew carried the same word to the passengers. In less than 5 minutes there was another explosion. Mr. Alfred Vanderbilt’s suite was full of black smoke and wall dust.

Then the ship took a list and the passengers got excited and not more than two or three minutes afterwards the ship went down. I lost Mr. King. One of the lifeboats was already swung out and I jumped in, but there was no one to lower it. I went down with the boat and my foot was caught in some wreckage. When I came up, I reached an overturned lifeboats and was on it for four hours, with twenty others slipping off and on all that time. At six o’clock PM we were picked up by a torpedo boat. There were only six of us left, all exhausted. We were then well taken care of and brought to Queenstown.

James Leary

Both accounts tell the same story, yet one if left wondering about the various details added to the 1917 rendition. Did Leary embellish, or was he simply able to expand upon his 1915 story because the 1917 version was given verbally rather than in manuscript form?

James Leary died on September 12, 1933, in Hollywood, California.

Thomas Boyce King, Leary’s friend and coworker from Brokaw Brothers, did not survive the disaster. His body was recovered, and a photo of his coffin was printed in the UK newspapers. One photo caption described him as an “American millionaire” but, in fact he was merely comfortably well off. He had earned approximately $9500.00 per year for the last five years of his life.

He was buried at Union Cemetery in Rye, New York, near the home he shared with his wife, Anna, and son Thomas Boyce King, junior. Mrs. King married a UK national by the name of Samuel Stansfield, who survived only into the 1920s and who, upon his death, was buried beside Mr. King. Anna King Stansfield died in 1946 and now rests with both of her husbands. Thomas Boyce King, junior died in November 1974, at age 71, in Yonkers, New York.

Lifeboat #14. One of the keystones of the Lusitania disaster story is that no boats escaped from the port side, save for those collapsibles that washed free of the ship as she foundered. However, Boat 14 was successfully lowered during the final stages of the sinking, and carried three or four of her original passengers to safety. The rest of her complement was dispersed, as she repeatedly capsized and ejected them into the ocean.

The experiences of those from Boat14 who survived paint a grim picture of men and women in a futile struggle; bailing with their hats, handbags, shoes and probably hands; as a single missing plug and, perhaps, structural damage, allowed their boat to fill with water and overturn.

Virginia Loney was resting in her family’s cabins, B 85-87, accompanied by her maid, Elise Boutellier when she heard the explosions. “I had no idea what had happened, but joined in the mad rush for the deck.” She found her parents, and waited with her mother, Catherine Loney, and her maid, while her father, Allen Loney went below to get lifebelts.

Charles Hill’s first instinct, after the explosion, was to check on his friends Beatrice Witherbee and Mary Brown, a mother and daughter traveling to a new home in London with Beatrice’s young son Alfred. He found their D Deck cabin empty, and noted water coming into the ship from the porthole in the passageway. He ran to his own cabin, B-110 to get his dispatch case and overcoat.

Teenager George Wynne was in the ship’s vegetable locker when the torpedo struck. He ran down the alleyway to the kitchen, and could hear the pots and pans falling from the stove and clattering to the floor as he exited the room. His first instinct was to find his father, Joseph Wynne. George made his way aft to a crew area on C Deck, where he located him. The two men went to the boat deck, to see what could be done. Joseph Wynne realized that his son could not swim, and told him to stay put while he went to the crew’s quarters to get someone.

William McMillan Adams and Arthur Henry Adams

William McMillan Adams and his father watched the crew, and “saw only two boats launched from this side. The first boat to be launched, for the most part full of women, fell sixty or seventy feet into the water, all the occupants being drowned.”

But, finally, the Lusitania righted herself. The crew, seeing this as a last chance to get a port side boat away, began filling Boat 14 as quickly as possible.

Robert Cairns found #14 swinging inboard. He joined others and, taking five or six paces back, pushed the boat over the side of the ship so that it could be loaded.

The Lusitania’s barber, Lott Gadd found a crowd waiting at Boat 14. He took charge of the boat, for no one else seemed to know what to do.

Lott Gadd

Courtesy Caroline Windsor

Charles Hill ran aft along the deck. He tried to enter a lifeboat, but was rebuffed by a woman who told him that it was too full. He noticed that only a few people had entered #14, the next boat aft, and so he jumped in.

Virginia Loney was standing at the perimeter of the crowd at Boat 14 with her family. Her father noticed that there was still space in the boat that was about to be lowered. She edged forward, and “He (Allen Loney) ordered me to get in. I protested, but finally obeyed.” She felt the boat begin to lower, as soon as she got in. She was surprised that the crew did not wait for others, such as her parents, to enter.

George Wynne was still waiting by the rail for his father when a man told him that, with the ship about to sink, it was no use waiting for anyone. The man urged him to jump into the lowering boat, which he did. Joseph Levinson, standing on the B Deck promenade, watched the boat making its descent. He jumped in as well.

Robert Timmis was one of those attempting to help with the lowering of Boat 14. He stood among the crowd, and “kept them clear of the lowering rope, when suddenly it began to pay out like lightning. I got clear and then rushed to the side and looked over; the boat was safely in the water with its passengers.” Robert Cairns, aboard #14, felt the boat tilt up, and saw a few passengers fall out. He noted that the boat began to leak immediately upon entering the water. Charles Hill recalled that Lott Gadd loosened the block holding the rope to the lifeboat prematurely, causing the boat to slip down the falls: “She dropped almost vertically, spilling out into the sea all those near the stern.” Mr. Hill thought that it was the impact with the water which started the craft leaking. Gadd denied that, saying that all it did was make the boat bob around in the water for a few moments. He claimed that the boat was damaged as it scraped over rivets along the ship’s side.

Annie Sharpe, a passenger in #14, recalled that the boat immediately began filling with water. She believed that the boat’s plug was not in. Miss Sharpe saw a woman begin bailing with her handbag, and felt annoyed when she noticed a gentleman sitting and doing nothing. She grabbed his Porkpie Hat and began to bail with it. George Wynne took off his slippers and tried his best to bail with the flimsy apparel. Robert Cairns waited until the water rose up to his knees, before he jumped from Boat 14, along with several other occupants.

Virginia Loney believed that it was suction from the Lusitania going down that capsized #14, for the boat was only a few yards away from the liner when she took her final plunge. Miss Loney had been looking up at the ship, where she believed that she could see her parents on deck, when she was suddenly catapulted into the water. She was “drawn ever so far down” by dying Lusitania’s wake.

Many of Boat 14’s occupants climbed back aboard the damaged craft, but with each subsequent capsizing, passengers were lost. Annie Sharp kept count each time the boat rolled over, and noted that by the sixth time most of the original occupants had disappeared. Annie had a baby thrust into her arms by a drowning mother, but noticed that its eyes were glassy. When the boat capsized, again, she let it go.

Charles Hill watched Lott Gadd swim away from the overturned boat, and realized that he had not paid the barber for his week’s shave. An old man, and a woman with a child clung to him as he tried to climb back aboard #14.

George Wynne held on to one of the lifelines, before hauling himself back into the boat. It capsized again. Wynne eventually lost consciousness.

Joseph Levinson, after being ejected from the capsizing boat, “found that I could keep afloat quite easily by treading water, just like walking the street, so I moved among the people telling them what to do and in this way I think I saved some lives.”

Virginia Loney saw a lifeboat picking up survivors and swam to it. She was pulled in, and was soon aboard a fishing smack. George Wynne awoke aboard the vessel Indian Empire, and was told that he had been found tied to some wreckage. He would later learn that he had placed on the wreckage by Sixth Engineer Dunn.

Charles Hill and Annie Sharpe were among the few people who remained with the waterlogged Boat 14 until rescued. Elizabeth Duckworth, in her well known account, recalled coming across a swamped lifeboat with only a few people in it when she, and a crew of men, returned to the disaster scene to search for survivors after the arrival of rescue ships. She was told that the other occupants were somewhere back in the water, lost when the boat repeatedly capsized. It is likely that Mrs. Duckworth was referring to Boat 14.

…and the next instant the keel of the ship caught the keel of our boat, and we were thrown into the water.

Accounts by George Kessler, a New York wine merchant, and Norman Ratcliff, a London businessman, hint at the possibility that a second port side lifeboat was lowered in the last minutes only to be destroyed as the ship sank beside it. The details of Kessler’s accounts remain consistent from telling to telling, but are not entirely consistent with accounts left by survivors from Boat 14. Kessler’s boat had some sort of accident in lowering, as did #14, but he was emphatic that the boat he was in was struck by the sinking ship and overturned almost as soon as it touched the water. Survivors from Boat 14, as well as those who watched from aboard the ship, were consistent in their statements that the boat survived long enough to struggle clear of the ship, fill with water, and capsize. Details of Mr. Ratcliff’s account correspond with the majority of others left by portside survivors, and he too was in a boat that was struck the ship as she plunged downward. It seems that a boat filled with crew, and a handful of passengers, among them George Kessler, Norman Ratcliff, and Mr. and Mrs. Bruno (referred to as “Berth” in his early account, and by their proper names in a later retelling) may have free-fallen from the port side boat deck very late in the sinking, only to be struck by the hull of the Lusitania, and capsized, as the liner foundered.

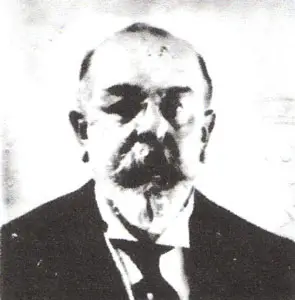

Norman Ratcliff

English businessman Norman Ratcliff left an excellent account of the disaster, containing another reference to the disastrous “The watertight compartments are holding out” canard used to calm passengers. Mr. Ratcliff, of Gillingham, worked for the London manufacturing firm of Messrs. Stern, Ltd., and was returning from an extended business trip to Japan, when he found himself trapped aboard the sinking Lusitania:

I had been out to Japan for the firm on business since the beginning of the year, and was on the return journey having spent some time in San Francisco before I reached New York. When the Lusitania started, there was some talk among the passengers about the threat by the Germans that the ship would be attacked, but it was regarded as a piece of bluff, and no one was alarmed by it. We had a delightful trip, but a few hours before the disaster occurred we were in a dense fog, and the horns were continuously sounding for a couple of hours. Then the fog cleared away, and we were going at a moderate speed.

I was sitting at lunch in the main dining saloon, when I heard a sudden report, for all the world like that (striking his fist) We knew that it was an explosion of some kind- it was like a muffled explosion- and we wondered what had happened. Nearly everybody in the saloon immediately got up from their seats, and started for the next deck. The stewards called out “Take it gently! Let the ladies get out first!” There was no confusion or panic, and everyone left the saloon as quietly as could be.

When I reached the deck I saw that the big ship had immediately listed over. All the boats – twelve on either side – had been swung out two days beforehand and the passengers who had already provided themselves with life belts were getting in to the boats. The stewards called out “Don’t lower any boats. We’re all right. The watertight compartments are holding out” Some of the passengers began to leave the boats, but the ship listed still further and they got into the boats again as speedily as possible.

Something went wrong with the first boat that was lowered. It tipped upon one end, and all the occupants were thrown into the water. The ship was gradually settling down, and when I saw that the inevitable was coming, I took off my coat and waistcoat and boots and threw them on the deck. There were some rafts near the boats, and I cut three of them free with my knife. When the deck upon which I was standing was only six feet above the water, I jumped into a boat which was nearly full of people. I had just succeeded in cutting away the falls when the ship came right over and our boat was struck and went under.

What happened then I don’t know, but I came to the surface and found that the boat had disappeared. The water was full of people all around me, struggling to catch hold of anything. It was impossible to do anything for any of them. I was somewhat dazed for a time, through going under the water, but I soon recovered my senses. On looking around, I saw a ship’s locker about thirty yards away, and I swam for it and hung on to the side of it for a considerable time. Another man who I believe was one of the ship’s crew followed me and held on to it in the same way.

After about an hour I made a desperate effort and succeeded in clambering up to the top of it, and this gave me a rest. I grabbed and secured an oar that was floating by, and as I was drenched through and very cold, I worked the oar to keep myself warm. My companion in distress was too heavy to get on top, but he continued his hold and was one of the saved. To add to our troubles, another swam up to the box and caught hold of it, but he was almost gone. With the assistance of the first man who joined me, I pulled him on to the top of the locker, and he laid down on one corner and myself on the other, waiting for help.

We kept in that position for a good time, and we were all right when we remained so, and I picked up another oar. The poor fellow was too far gone, and he didn’t have the strength to use the oar. Then the locker suddenly rolled over and we were all three thrown into the water again. The man who had been on top with me disappeared and I never saw him again, but my first companion regained his hold and again I succeeded in getting on top, and I afterwards opened one of the cupboard lids and remained on that. There were corpses floating all around us owing to the cold and exposure. It seemed a terribly long struggle until, we saw trawlers coming up in the distance and making for the boats full of passengers. Eventually we were rescued by a boat that returned from one of the trawlers, and taken on to the trawler Bluebell.

Mr. Ratcliff died in Maidenhead, England, on November 9, 1959 at the age of 80.

George Kessler remembered:

I saw the crew taking the tarpaulins from the boats, and I went up to the purser and said “It’s alright drilling your crew, but why don’t you drill your passengers?” The purser said he thought that it was a good idea, and added “Why not tell Captain Turner, sir?” So, the next day I had a conversation with Captain Turner, and to him I suggested that the passengers should be given tickets with a number denoting the number of the boat they should make for in case anything untoward happened, and that it seemed to me this detail would minimize the difficulties in the event of trouble. The Captain replied that this suggestion was made after the Titanic disaster, but that the Cunard officials thought it over and considered it impractical. He added that of course he could not act on the advice given, because he must first have the authority of the Board of Trade.

I talked with the Captain generally about the torpedo scare which neither of us regarded as of any moment. The Captain – you understand that we were smoking and chatting – explained his plans to me.

He said that we were then slowing down – in fact we were only going eighteen knots – and that the ship would be slowed down until they got somewhere further on the voyage, and then they would go at full speed and get clear of the war zone. I asked him what the war zone was, and he said “500 miles from Liverpool.” According to the next day’s run, about two hours before the disaster occurred, we were about 380/390 miles from Liverpool, so we were in the war zone and we were only at a speed of about eighteen knots at that critical moment. For two days previous, as well as I remember, the day’s run had been 506 and 501, and on Thursday it was 488. I was playing bridge on Friday when the pool was put up on the day’s run, and I heard twenty members go to 493. I thought it would be a grand speculation to buy the lowest number, because we were going so slow. I did but it, and paid $1.00. The sum of the pool was between $300 and $350 and I was the winner. The steward offered to hand over the money if I would go to his cabin, but I said he could pay me later.

Shortly after the steward had left me, I was on the upper deck looking out over the sea. I saw, all at once, the wash of a torpedo, indicated by a snakelike churning of the surface of the water. It may have been about thirty feet away, And then- thud! Mr. Berth, and his wife, of New York, first class passengers, were the first I spoke to. I should say that about this time all the passengers in the dining saloon had come up on deck. The upper deck was crowded, and of course all the passengers were wondering what was the matter- few believing the truth. Still, the crew began to lower the boats, and then things began to happen very quickly. Berth was trying to persuade his wife to get into a boat. She said she would not do so without him, and he said “Oh, come along, my darling. It will be alright.” I added my persuasions to his. I saw him help her into a boat, then the falls suddenly slid through the davits. I fell into the boat and we slipped down into the water over the side of the liner which was bulging out, the list being the other way. Then the boat struck the water, and after a few seconds- it may have been a minute- I looked up and cried out “My God! The Lusitania is gone!” We saw the entire bulk of the liner, which had been upright just a few seconds before, suddenly lurch over away from us. And the next instant the keel of the ship caught the keel of our boat and we were thrown into the water. There were about thirty people in the boat, and I should say that all were stokers or third class passengers. There may have been one or two other first class passengers; I cannot recall who they were.

When the boat was overturned, I sank and I thought I was a goner: however, I had my lifebelt on and rose again to the surface. There I floated for possibly ten or fifteen minutes when I made a grab at a collapsible lifeboat at which other passengers were also grabbing, and we managed to get it shipshape and climbed in. There were eight or nine in the boat, stokers, except one or two third class passengers. It was partially filled with water. In the scramble the boat was overturned, and once more we were pitched into the water. This occurred, I should say, eight times, the boat righting itself usually, and before we were picked up by the Bluebell six of the party of eight or nine were lying drowned in the bilge water which was in the bottom.

My God! What can America do? Nothing will bring back these people to life. It was cold blooded deliberate murder, and nothing else; the greatest murder the world has ever known. How will going to war mend that? I hesitate to give an opinion on matters which are purely technical, but still it seems to me, as a landsman, and one who has crossed the ocean many times, that the safety of the Lusitania lay in speed.

We were in the war zone by 140 or 150 miles, and every moment that we dawdled at fifteen or eighteen knots was an increase of our risk of being torpedoed. Again – and of course I merely make a comment – I can’t understand why there were no destroyers or patrol boats about. We certainly had been led to expect there would be when we reached the war zone.

George Kessler had been noted for his high living before the disaster, and had garnered much press space for his lavish parties in both New York City and London. He recalled, after the disaster, that while adrift he had determined that he would make a difference, by channeling his money and time into helping war victims.

Kessler’s opportunity to make a difference presented itself when he met newspaper publisher Sir Arthur Pearson. Pearson, a blind man, had founded St. Dunstan’s; an organization that aided men blinded in the war. George and Cora Kessler founded The Permanent Blind Relief War Fund. They met, and were endorsed by, Helen Keller.

Their fund, which was called to action again during World War 2, survives today as Helen Keller Worldwide. George Kessler died at age 57, on September 13, 1920.