The Public Be Damned: One Black Week in 1875 – The SS City of Waco

The Loss of the City of Waco, November, 1875.

“If Mallory & Company, This Incompetent Inspector, and Three Careless Customs House Clerks Met The Same Doom Which They Prepared For Others, the Public Would Not Have Regretted It.”

Part Two : The Loss of the City of Waco, November, 1875.

On the same day that the Pacific’s Neil Henley was rescued after nearly 70 hours adrift, an even more regrettable and reprehensible disaster involving a U.S. coastal liner took place off of Galveston Texas. 50 or more passengers and crew had sailed from New York City aboard the Mallory Line’s City of Waco, and they were only a few hours from safety, and surrounded by other vessels, when a particularly horrible fate overwhelmed them. And, in this case, none lived to testify.

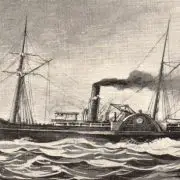

The City of Waco was a new ship, unlike the Pacific. Built in 1873, she was a single screw vessel 238’ long by 36’ wide, had two passenger decks and was provided with four watertight bulkheads. Her insured value was $200,000.00, and she was classified by Lloyd’s as an A-1 vessel. When she sailed for Texas she carried aboard her a mixed cargo, ranging from dry goods to bricks to groceries. She also carried, in a very obvious manner, an illegal cargo that would kill her entire complement within sight of shore and in full view of the crews and passengers of seventeen other ships.

When she arrived off Galveston on the 8th of November, a violent Gulf storm was blowing, and she was compelled to wait the bad weather out before entering harbor. Shortly before midnight a fire broke out below, and when it reached the cargo stowed on the liner’s open deck the end result was predictably grim.

Since none were saved, the columns of the Galveston and New York papers best give voice to what happened.

A GREAT DISASTER

At about one o’clock Monday night, as near as can be ascertained from various sources of information, the Mallory steamship City of Waco, which arrived in the outer roads four o’clock Monday afternoon from New York took fire and burned to the water’s edge. At twelve o’clock yesterday she went down out of sight. The wind at the time the fire broke out was blowing a gale from the southeast, and the passengers and crew, excepting as such those who may have perished in the flames, it is supposed and hoped, put off in the ship’s boats of which there are four, besides a life raft. From the southeast, the wind went around to the north during the morning yesterday and if the boats were afloat with their human freight the general opinion is that they would not make headway against the wind, and while the wind was from eh east, they dare not attempt to make the beach on account of the heavy seas. On the other hand there are those who believe the boats could easily have made Bolivar Point.

A reporter to the NEWS repaired to the office of the Mallory agent in this city, Captain J.N. Sawyer, and while there learned that the first mate of the Fusi Yama, an English steamer which lay a quarter of a mile westward of the City of Waco, had reported to his captain. G.O. Hayward, who is in the city, that a boat or raft with people aboard passed his vessel about three o’clock yesterday morning going westward. The could not say whether there were other boats beside the one he saw. The sea, he reported, was running very high at the time, and small craft could only submit to the mercy of the elements and drift before the wind. Captain Sawyer, as soon as he heard , yesterday morning, of the disaster dispatched carriages east and west in search of the boats and to look out for them just in case they made shore. At a late hour last night, all expeditions had returned with no tidings of the crew or passengers of the ill-fated steamer.

Captain Wolff, one of the best pilots in these waters was aboard the City of Waco when she took fire. Captain S.P. Greenman, commander of the vessel, an old seaman and fully acquainted with the Gulf coast was also on board. It is thought that if the lifeboats started fairly they will be successfully managed by these experienced seamen, though, on the other hand, there are difficulties to be met that no human power can surmount. The north wind that prevailed all day yesterday drove them farther out to sea, as it was not possible for light craft to make headway against it.

The City of Waco, Captain S.P. Greenman, arrived Monday and lay in the offing just off the outer bar. She was preparing to unload, and the passengers would have come ashore yesterday.

The course that led to her taking fire can not be learned until some one board of her at the time can be seen. Seamen with whom the reporter conversed think it possible she was struck by lightning, but this is merely a conjecture.

But so far as the actual cause of the conflagration is concerned all is conjecture. Nor is it positively known whether all the people aboard were able to get off in boats and there is no clue to the whereabouts of any of them. All is conjecture with regards to their fate.

The NEWS dispatched reporters, one west along the Gulf beach and one eastward with searching party of the Buckthorn. They returned after dark last night and reported as follows.

The reporter who was sent along the Gulf shore on horseback returned to the city after a day’s jaunt, with no tidings of the missing passengers and crew of the ill fated steamer.

After riding twenty miles along the beach, down the island, and inquiring of the people he met on the way, he saw only a barrel that was being slowly washed ashore, some nineteen miles from the city, and a shoe such as is worn by a sailor coming ashore through the action of the water. The wind was blowing strongly offshore and it was utterly impossible for a small boat to have made landing on the island after one o’clock p.m.

There were several teams on the Gulf beach during the day, several of which went nearly to the end of the island, but they all reported no sign of the wreck, save those mentioned above.

A German, whose name the reporter could not learn, stated that he saw a small boat with a “leg of mutton” sail going to the westward early this morning, but he, not knowing of the loss of the steamer, did not pay particular attention to it.

Three were no signs of any bodies being washed ashore as far as the reporter went and as far as he could hear from, and the most careful examination was made of every floating object during the entire distance traversed by him.

The steamer Buckthorn, Captain Wilson, left Labadie’s wharf at 11:45 yesterday forenoon in search of boats, rafts or passengers and crew that might have escaped from the burning steamer. The first sight of the burning vessel was obtained as the Buckthorn rounded the point near the hospital, but nothing was to be seen but a cloud of smoke and the dim outline of the ship, as the wind would for the moment dispel the smoke. At 12:10, when near the breakwater at the east end of the island, a dense cloud of smoke was seen to envelope the ill-fated steamer, and when the obscurity was somewhat dispelled by the wind, not a vestige of the ship as to be seen. She had sunk almost instantly, going down by the stern, but from what immediate cause must forever remain one of the mysteries of the sea.

The Buckthorn, on nearing the bar, encountered a heavy sea, but those who should have known declared it comparatively calm as compared with that which prevailed during Monday night and early yesterday morning, the result of a gale which prevailed from the east north-east at the rate of forty miles an hour.

The ship Caledonia was lying at anchor a little way to the westward of the steamer. No information could be obtained on the Caledonia, and the cruise was continued. The next vessel spoken was the English steamship Fusi Yama. From the Fusi Yama it was learned that what appeared to be a raft had floated by them at 2 o’clock yesterday morning, on which they thought they could distinguish a number of persons. They attempted to launch their boats to go to her rescue, but where prevented by something that could not be understood in consequence of the wind and sea.

The steamer San Marcos was next approached, where it was learned that the fire on board the City of Waco was first observed at about midnight. Nothing unusual was noticed on the unfortunate ship until she appeared wrapped in sheet of flame, having, in the opinion of the speaker, been struck by lightning as he could divine no other cause for the sudden and explosive outbreak of the flames. Nothing was seen or heard of any of the boats of the City of Waco by the watch on the San Marcos, which was lying about three miles from the burning boat.

The Buckthorn, having done all that was possible under the circumstances returned to her berth, arriving at about 6:45 yesterday afternoon.

The sea outside the bar on Monday night was unusually rough, the wind was blowing a gale of forty miles an hour from the east-northeast. There were fifteen vessels riding at anchor on the bar when the City of Waco came in and anchored at five o’clock Monday afternoon. Of the fifteen vessels in the roadstead, thirteen of them were directly to the leeward of the position taken by the City of Waco. Nothing unusual was observed until, as described by the steamship San Marcos, the ill-fated vessel appeared to be instantly wrapped in flames. While it would, with the prevailing wind and heavy seas, have been impossible for any of the vessels near to render assistance to the burning steamer, it would have been equally impossible for boats or rafts from the City of Waco to have passed the thirteen vessels immediately and directly to the leeward of her without being discovered if not rescued. The judgment of the experienced seamen who went in search of information yesterday, and of most others with whom we have conversed, is that the catastrophe was so sudden and unexpected, and the destruction so rapid and complete that it was found impossible to launch a boat or raft from the deck of the doomed ship, and that every soul on board either perished by the flames or went down with the wreck.

THE CITY OF WACO DISASTER

Explosion on Board the Burning Ship.Few of our citizens were so immersed in business yesterday but that they could spare a few moments during the day to inquire about the fate of the passengers and crew of the City of Waco, and so great was the anxiety felt in all circles that little else could be heard on all sides but conjecture, theories and conclusions concerning the possible terrible disaster. Indeed, a pall seemed to have suddenly fallen over the city and the public anxiety was wrought up to an even higher pitch when night set in without bringing the least bit of intelligence concerning the fate of the persons who composed the human freight aboard the doomed vessel. Telegrams were received by several of our citizens from friends of the Waco’s crew and passengers inquiring of their fate, and at this moment many hearts are bowed down in grief and sadness from which they can only be aroused by good tidings. But of such there seems no ground of hope. All the circumstances of the disaster point to the conclusion that the vessel was suddenly wrapped in flames leaving so little time for action that the sleeping inmates must have perished. It is learned that a quantity of oil was stored on the upper deck of the vessel, as she had much of this kind of freight on board, and it was usual to store it above the hatches so as not to affect the rates of insurance.

The statement of the mate of the Caledonia is given below, also the result of the cruise of the Buckthorn, which left the city yesterday at 11 a.m. and returned some time after midnight.

The ship Caledonia, Capt. Potter, was at anchor almost immediately astern of the City of Waco and sufficiently near for those on board to see and hear what occurred. At the time of the disaster, Captain Potter was ashore , and the Caledonia was in charge of the mate and watch, the crew not having been sent aboard.

Mr. Cahill was on the quarter deck of the Caledonia, on the lookout, when he heard an explosion and felt the concussion. Looking in the direction of the steamship City of Waco he saw the vessel was enveloped in flames. After some half an hour he heard cries for assistance and saw some half dozen persons in the water. In a few minutes after, he saw two persons float by on a fender or piece of wood. He made all the preparations possible for rendering assistance should anyone drift near enough to the Caledonia to avail themselves of what he could do. He got out life lines and life buoys, but being without assistance could not launch the boat. The sea was running high at the time and the wind was blowing a gale.

The two men on the fender were drifting directly toward the steamer Fusi Yama, and Mr. Cahill thought they would be able to reach that vessel and possibly be picked up. Mr. Cahill heard the cries and saw at least half a dozen persons in the water, beside the two mentioned as floating past on the fender or piece of wood. After hearing the explosion and noticing that the steamer was completely enveloped in flames, he watched her narrowly. The fire, after something like a half an hour, lost the fierce character that prevailed for the first minutes, but continued to smolder and burn, occasionally flashing out brightly, and then showing nothing but smoke and steady, slow, combustion.

The burned ship rolled heavily, her decks being even with the waves at every motion. The foremast of the City of Waco went by the board at about half past twelve o’clock on Monday night. Mr. Cahill was so close to the burning wreck that he could distinctly hear the hissing sound when flames and water met, as the waves would break over the bulwarks of the doomed vessel. When the wreck sunk, he could clearly distinguish the bubbling of the water as the seething mass slowly disappeared below the waves.

This statement of the mate of the Caledonia is the first authentic account of any of the circumstances attending the melancholy catastrophe. It seems certain that the disaster was the result of some sudden and unexpected cause- that it was so overwhelmingly disastrous that the passengers and crew had no opportunity to escape and that none of the Waco’s boats were launched, and unless by some lucky accident the two men on the fender succeeded in reaching the shore at some point to the westward of the island, or were picked up by a passing vessel, every human being aboard the ship perished.

The wreck lies in about six fathoms of water, but whether an effort will be made to raise the hull or not, we are not informed.

The steamer Buckthorn, which had been cruising about during yesterday in order to rescue any of the unfortunates of the City of Waco that might still be alive returned last night without any tidings of the missing ones.

The search will not be given up, and Captain Sawyer will send the Buckthorn out again today.

Yesterday, the Buckthorn found the burnt remains of one of the boats of the Waco, together with some oars and a part of the steps that led from the upper cabin to the deck floating in the Gulf some fifteen miles from land and about twenty five miles from this city, and this, too, seems to corroborate the idea that none of the unfortunate passengers were saved.

(Galveston Daily News, November 11, 1875)

THE WACO MURDER

In yesterday’s telegrams was an account of the observations of Rev. Peter Moelling, of Troy, New York, whose daughter perished on the City of Waco. It seems that he accompanied the young lady to the steamer on the day of the sailing and remained on board three quarters of an hour. He saw a large number of barrels of oil brought in and placed on the after part of the upper deck; also a quantity of boxes containing tin cases as are used for the shipment of what is called “astral oil” these latter being stowed forward. From appearances, this dangerous freight was smuggled on to the ship with the connivance of her owners, who were evidently anxious to keep the passengers ignorant of the peril in which they were to be placed. The oil did not come aboard until the last moment and was handled by the ship’s stewards instead of that portion of the crew who usually have charge of the storage of cargo. So impressed was Reverend Moelling by the impending peril that he would, if possible, have removed his daughter; but circumstances prevailed and she shared the same awful fate as her companions.

This sad story is abundantly conformed by statements in the New York papers. An examination oat the Customs house reveals the fact that Mallory & Co., the owners, shipped on the Waco 900 cases of petroleum- each case holding a five gallon can- consigned to the Gas Light Company of Galveston. The word “petroleum” was badly written in the manifest, which is the reason alleged by the Customs House officials for permitting the shipment. The supervising inspector of New York says that the Waco had no license for carrying oil, but he virtually acknowledges that it is a common thing for coastwise steamers to do so, though they thereby forfeit their insurance and render themselves liable to prosecution. The law is explicit, and forbids the transportation of oil in any passenger steamer when there is any other mode of conveyance. If the inspector knew this law was being persistently violated, why did he not arrest the guilty parties? Why has he shut his eyes to what was going on until a terrible disaster resulted from his criminal negligence?

If Mallory & Co, this incompetent inspector and three careless Customs House clerks had met the doom which they prepared for others, the public would not have regretted it; but as they are alive and within the reach of justice, we hope they will get it. Let the government investigate the matter thoroughly, and mete out punishment as the crime deserves. But Mallory & Co. should not be made scapegoats of the whole business. The oil could not have been shipped without a preliminary manipulation of the customs house authorities, and they deserve even heavier chastisement than the unscrupulous owners. The destruction of life which accompanied the loss of the Waco is nothing but wholesale murder, and the men who were accessory to the crime should receive appropriate treatment.

New York World.

THE CITY OF WACO DISASTER

Opinion of the Press.Mssrs. C.H. Mallory & Co., owners of the burned steamship City of Waco received a telegram from their agent at Galveston, J.H. Sawyer, yesterday morning, stating that he had been engaged with a tugboat in searching along the coast after dead bodies and also that he would resume the search today. The firm do not deny that the City of Waco carried considerable oil contrary to the regulations of steamboat inspectors; but one of the firm said yesterday that it was the custom of nearly all steamships to carry oil but the owners of the line were not always aware of it as a shipper might send considerable quantities of oil by the boats as ‘merchandise’ the owners not taking the trouble to find out what the ‘merchandise’ consisted of. One consignment of oil, consisting of 500 barrels of petroleum was shipped on the City of Waco by C.H. Hill & Co. Mallory and Co. was of the opinion that the fire started below deck and spread in the oil which was mostly above. The company refused to tell who the principal shippers on the steamer were. Inspector of Steamboats John Matthews says that the inspectors were not responsible for the acts of the owners of the steamer after an examination of the vessel had been made. Any company may send to the inspector’s office and require an inspection of a vessel to ascertain that there is a place where refined petroleum may be safely stored. A certificate having been given in that effect, if the company owning the vessel assumes the responsibility of carrying oil to ports with which there is communication by sailing vessels they assume every risk of invalidating their insurance policies and incurring the penalties imposed by the law. The inspectors are not bound to infer that oil is to be carried. No certificate of examination, however, had ever been given to the City of Waco. It is understood that Supervising Inspector Low will bring the case to the notice of the District Attorney.

When will our people learn again to respect the law of the land, and when will they obey it? When shall we have a system of official accountability and a Federal Executive vigilant to enforce the laws?

The law of Congress of February 28, 1871, for the better security of life on board of steamers carrying our flag. covers some twenty pages of the statute book. It is a most elaborate piece of legislation. It forbids certain articles to be carried as freight or used as stores.

The public waits, with curiosity and solicitude, the action of the government in this dreadful business. At present it thinks it sees a new reason why no one should travel on an American steamer who can avoid it.

St. Louis Republican.

STATEMENT OF THE PILOTS

We the undersigned subscribers went on aboard the pilot boat called the Eclipse at about half past four o’clock on the morning of the 9th day of November, 1875, reefed the mainsail and took the bonnet out of the jib, on account of the strong wind blowing from the north northeast, and proceeded out to the rescue of the steamship reported to be burning in the offing, at the anchorage off the city of Galveston. We reached the scene of the burning vessel and found it to be the steamship City of Waco, and also found her to be one mass of flames and smoke. This was about 7 o’clock a.m.; wind blowing at the time from north northeast but changed very soon thereafter to the northward. We kept a lookout for signals or boats, but saw neither. We then proceeded to the steamship Fusi Yama, at anchor close by, and spoke the mate, asking him what time the ship took fire. He replied that he discovered the ship on fire first at about half past 11 o’clock on the night of Monday, the 8th of November. We then asked him if he had seen anything of the boats of the City of Waco. He replied that he was getting boats ready to go to the assistance of the burning steamer, when he discovered the boats of the City of Waco passing the Fusi Yama going west, which statement led us to suppose that the boats had gotten into the harbor and were all safe, so we at once returned to the city to inquire if the boats had been seen or heard of. After due inquiry, we ascertained that nothing had been seen or heard of them, hence we again put to sea, returning to the burning steamer. Finding that she would soon sink, we placed a small buoy to mark the spot and proceeded to the westward. About twelve or fifteen miles south and westward of the fleet of vessels at anchor off the outer bar, we discovered the foremast, with foreyard gaff, and sail attached, floating. The lower part, or end, of the mast was burned off, to all appearances, very square, and from the appearance of the lower end of the mast it must have been burned under deck, as the rest of the mast bore no signs of having passed through fire. Hence, all the foregoing circumstances taken into consideration, we hereby express our belief that in our judgment, the fire which destroyed the City of Waco originated under the deck of said steamship.

J.B. Sabel

Louis Best

Wm. Scrimgeour

STATEMENT OF CAPTAIN SAWYER AND OTHERS

We the undersigned left the bar off Galveston at seven o’clock a.m. of the 10th day of November, 1875, in the pilot boat Eclipse, and steered in southerly direction in search of survivors from the burned steamer City of Waco. At 11:30 a.m., when about 30 miles south of the fleet of vessels at anchor outside Galveston bar, spoke the steamer Buckthorn, Captain Irving, who informed us that he had been constantly cruising, and had passed articles belonging to the burned steamer, but had not seen any persons clinging thereto. He was going to continue the search in a southwesterly direction; the Eclipse was, therefore, steered west-southwest, and at 2 p.m. came up with scattered boxes marked “(J.P.) Galveston” and continued to pass more or less of the above described cases during the afternoon of the same day. At 4 p.m. was alongside of what we supposed to be the Waco’s foretopmast, it having been broken off in the shieve hole, and the upper portion gone, otherwise it was entire and bright, with no appearance of having been touched by fire. During the night the wind was moderate, and the pilot boat sailed in a westerly direction. At daylight of the eleventh a boat was seen “bottom up” and was taken on board of the Eclipse. It had Mssr. C.H. Mallory & Co.’s house flag painted on each bow, and the words City of Waco painted in black letters on the stern. From a slight injury to the side, the imprint of footsteps on the thwarts, the chafing of the fresh paint by the warp, the lashings to the cover having been cut, and the absence of oars, which are usually lashed inside, we judged that some person or persons must have left the steamer in it. Continuing westward until the land was plainly visible, and discovering no other floating object, tacked and stood east southeast, with a fine breeze.

At 11 a.m. came up with large quantities of the same cases as seen on the previous day. Captain Best went in a boat to secure several of these, which, when taken on board, were found to contain each two tin cases of oil.

During Captain Best’s temporary absence from the Eclipse, she was worked close in to a dark object which, upon examination, was found to be the head or top of a skylight, which had been charred by fire on the inside. The outside was scorched but not charred, its outer surface being smooth and had the fastenings attached.

We worked several miles south of any visible floating object, and believing we were south of any drift from the lost steamer, kept off, and again coming up with the floating cases of oil steered angular courses from side to side of the floating cases without discovering any other object than a life jacket marked City of Waco with the neck strings tied in a hard knot, one end of which was detached from the jacket. Our object was life saving, hence we did not count the number of cases of oil seen by us, but we fully believe that we saw more than two hundred cases, none of which have any signs of having been burned or scorched.

J.B. Sabel

Louis Best

Benj. Manwaring

J.S. Sawyer.

THE CITY OF WACO DISASTER AND THE MOSEL EXPLOSION.

The following extract from a letter written by the local Board of Steam Vessel Inspectors of this city to the New York Board of Inspectors will be interesting:

We have not been able thus far to find out the origin of the fire on board the City of Waco. Capt. Sawyer stated yesterday to us that one of the divers had reported to him that there had been a big ‘fuss’ in the ship’s lower hold, conveying the idea that some explosive material had exploded in that part of the ship, which corresponds with the explosion heard by the mate of the ship Caledonia whose testimony we have taken.

That the loss of the Waco was occasioned by man infernal machine similar to that which was intended to demolish the Mosel seems hardly credible. Yet, according to the testimony of the owners of the Waco, there was no petroleum stored below the upper deck. The ‘fuss’ discovered by divers ‘in the ship’s lower hold’ must have been caused by something else, and according to the testimony of the mate of the Caledonia, there was an explosion somewhere. Beside, the mast of the Waco was burned off below deck and not above it as it would have been had the fire started in the oil forward. The fact that the inhabitants of some of the vessels in the offing at the time of the disaster heard no explosion may be accounted for when the raging of the disturbed elements is considered- a time when even a sudden explosion like that of a mine or dynamite may be drowned out or dissipated in great measure by the angry conflict of wind and waves. The Caledonia lay immediately to the windward of the City of Waco, and was the nearest vessel to her on that quarter. Hence, an explosion, if there was any, would have been heard on the Caledonia, if on any vessel in the offing.

The fearful suggestiveness of the destruction of the City of Waco is quite as great as that connected with the murderous dynamite which was designed to destroy the Mosel. It is earnestly to be hoped that the government authorities will probe to the bottom the marine catastrophe which cast such a gloom over the whole country, and from which not one human being escaped.

(Galveston Daily News, December 25, 1875.)

NOTICE FROM THE WACO

Divers who are at work on the hull of the ill-fated City of Waco are progressing in their work of taking out the cargo, and are of the opinion that most of the goods stored in the lower hull will be saved in good condition. Several days ago they recovered the safe of the vessel and brought it to the wharf in this city, where it now lies awaiting investigation.

(Galveston Daily News, June 13, 1876)

THE WRECKER RAPIDAN

Is again at her berth with a cargo from the City of Waco’s hull. The divers are at work in the lower hold and find an indescribable mixture of timbers, iron, freight and trash. They have been all over the hull, and give it as their opinion that the hull can never be raised as it is broken in several places.

(Galveston Daily News, July 12, 1876.)

WRECK OF THE WACO

Bids for the removal of the wreck of the steamer City of Waco, which was sunk just outside Galveston harbor, were opened at the office of Captain Riche, United States Engineer at 2 O’clock yesterday afternoon. Five bids were received and the amounts ranged from near $2000 to over $9000. The great disparity in the bids was not explained, as all of the bidders had not furnished specifications of the wreck which were made after an inspection and survey and the same project governed in each of the five bids.

The bids are as follows;International Wrecking S.&S. Company, Atlantic City, N.J.…$1,999.00

Charles W. Johnson, Lewes Del…..$4, 390.00

R.L. Bettison, Galveston, ….$7,895.00

Chase & Smith, Galveston….$9,925.00

Phil. S. Smith, Galveston.…$9,960The government had evidently anticipated that the work would be a little more expensive than the lowest bid, as $8,000.00 was available from what is known as the “Permanent Indefinite Fund For Removal of Sunken Vessels or Craft Obstructing or Endangering Navigation.”

The contract of the International Wrecking Company will no doubt be accepted. It will have to take the usual course through the departmental channels at Washington and then be returned to Galveston with the proper endorsement attached.

According to the contract, the work will have to be started within thirty days of acceptance, and completed within ninety days of the signing of the contract.

It will be left to the option of the contractor whether he blow up the wreck with dynamite, remove it piece by piece, or bring the whole heap ashore and sell it to a circus. The only requirement is that the wreckage be removed to give a clean depth of water of thirty-five feet where the vessel now interferes with navigation. All salvage, if any can be recovered from the water soaked and sea beaten craft will be the property of the contractor.

For these many years, the wreck has been a menace to vessels arriving and departing from this port. The wreckage, as located by the recent survey, lies in forty feet of water about six feet from the bottom, and occupies about a hundred feet in length one and three quarters miles from the outer end of the south jetty. It is in the path of vessels entering and departing from this port, and has been responsible for a number of accidents more or less serious. This dangerous spot is marked with a buoy as a warning to vessels and has been a source of annoyance to masters visiting this port.

(October 18, 1899)

Work on the destruction of the wreck of the Mallory Line steamer City of Waco is progressing rather slowly on account of the rough seas running at the point of the wreck, one and three quarter miles from the mouth of the jetties.

As the wreckage is buried in sand, the diver is experiencing considerable difficulty in placing the dynamite which is used to blow it up.

(January 20, 1900)

2005: From the Southwest Underwater Archaeology Society newsletter comes this interesting look at the present day remains of the City of Waco.

So, ultimately, the City of Waco affair raises more questions than it answers. She was quite obviously burning, fiercely, before the explosion seen by the San Marcos and seen and heard by the Caledonia, and one is left wondering if the fire was an unfortunate coincidence or if the Mallory Line was illegally shipping something combustible below deck. What of the 200 or so unburned cases of oil found floating by the Eclipse? My gut feeling is that the crew, aware of what was in the containers, was in the process of jettisoning them when time ran out. Why, when it became apparent that a massive disaster was unfolding, did the City of Waco not signal for help? Heavy seas or not, there were between thirteen and seventeen ships standing near, and it is unbelievable that with an explosive cargo on deck, and a fire of a duration long enough to burn a mast clean through burning below, no attempt at all was made to summon aid.

It seems that when the furor died down, the Mallory Line went unpunished, as did the owners of the Pacific. As unbelievable as it sounds, these two disasters were harbingers of worse to come, as both shipping companies were to experience additional disasters that seem, from the perspective of the 21st Century, to spring from an almost pathological disregard for human life.