The Public Be Damned: One Black Week in 1875 – The SS Pacific

The dual tragedies of the Pacific and the City of Waco

Part One : “You Placed Me in This Coffin; Cannot You Help Me Out?”

The Pacific Tragedy of November, 1875

One of the more tiresome canards in liner lore, is that up until April 1912 the general public had great faith in technology, and a sense of complacency that was, somehow, shattered by the Titanic disaster. Nothing could be further from the truth. The Victorians and Edwardians may have written innumerable articles and books voicing a politically correct, for the era, “things are getting better every day” sentiment, but in their day to day lives they viewed technology, and the corporate culture, with a jaundiced eye. And for good reason. This particular seven day stretch in 1875 illustrates, beautifully, why the Titanic and its revelations did not “wake the world up with a start.”

The loss of the Pacific, off Cape Flattery, Washington, on November 4th, 1875 may well have been the worst shipwreck, in terms of lives lost, in Pacific Coast history. At least 275 were known to have been aboard her, when she sailed from Tacoma and Victoria outward bound for San Francisco, but contemporary sources agree that the number was higher- in some cases far higher, numbering over 500 – and only two survived.

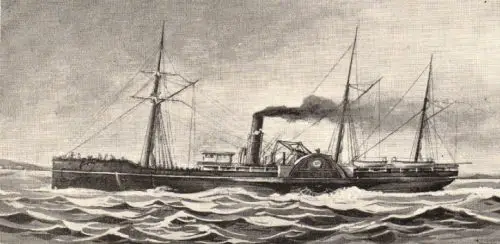

The Pacific was built in New York City in 1850, but was transferred to the West Coast while still new. She was a 900 ton wooden hulled sidewheeler, 225 feet long with a width of 30 feet. On her maiden voyage she distinguished herself by breaking the one day speed record for passage down the East Coast of the United States. Her prime years were spent operating between Californian and Central American ports, but by the early 1870s she was – even by the more relaxed standards of the West Coast trade – past her prime, and ca. 1872 was left to rot on the mudflats near San Francisco.

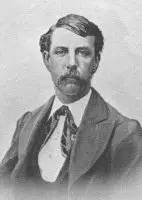

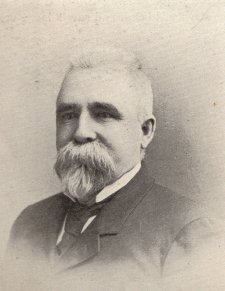

The 1874-’75 Cassiar Gold Rush generated such high demand for shipping that even the ancient Pacific was once again commercially viable. She was purchased by the newly formed Goodall, Nelson and Perkins Company of San Francisco, hauled from the mudflats and given a – mostly cosmetic – makeover, reportedly in the range of $40,000.00. She was inspected, repeatedly, and described as fine and sound sea boat, but, later, men who worked on the refit described her as being so rotten that her waterlogged wood could be scooped out with a shovel. In her final configuration she carried 115 passengers in First Class and 88 in Steerage, Captain Jefferson Davis Howell, younger brother of Varina Howell Davis, First Lady of the Confederacy, was in command of the Pacific during her final voyages. A nearly contemporary career summary of Howell survives:

[Howell] was born in Natchez, Mississippi, in 1841. He was educated at Annapolis and served as midshipman under commodores Tucker and Talbot at Charleston, South Carolina, in the James River Squadron under Captains Wood, Parker and Hunter, and afterwards at Charleston under Commodore Tucker in charge of a picket boat. After the fall of Charleston, he was a Lieutenant of Artillery in the Naval brigade under General Semmes, formerly of the Confederate Navy, was surrendered under General Lee’s cartel, joined Jefferson Davis at Washington, Georgia, was with him at the time of his capture and was then imprisoned at Fortress Monroe, where he was held for some time. Released, he went to Savannah, Georgia, where he was again imprisoned. Thence, he joined his brother in Canada and accompanied him to England. Returning by way of Portland, Maine, he was again arrested and sent to Fort Warren, where he was detained for a few weeks and released. He then returned to Canada, and thence to New York, where he went to sea before the mast. Returning, he was engaged with Pomeroy in the New York News. Tiring of this, he sailed as quartermaster on a ship bound for China, and from there went to San Francisco about 1870 and entered the service of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company as mate and Master, subsequently of the Oregon Steamship Company, and of the North Pacific Transportation Company as master of the steamships Idaho, Montana, Pelican and others.

History has not dealt kindly with Captain Howell. He is generally depicted as inept, at best; an inexperienced and incapable Master who was directly responsible for the deaths of at least 275 persons. However, he was educated at Annapolis, had spent a great deal of time at sea, the Pacific was not his first command as is sometimes stated, and a few months before the disaster he had distinguished himself with bravery during the stranding of the coastal vessel Los Angeles. Howell made one particularly poor decision on his final day, but as will be seen his reason for doing so was sound, and he was far from the buffoon his critics portrayed him as.

An Unfounded Report:San Francisco, Nov. 27- Henry Jelly, the surviving passenger of the Pacific contradicts the assertion that Captain Howell took command of his ship in an intoxicated condition. He says that the captain was on the bridge when the mooring lines were cast off; that he afterwards went into the pilot house and himself steered the steamer out of Victoria Harbor.

The report of Captain Howell being drunk is almost definitely an offshoot from an event that took place the day before the Pacific’s final sailing. Captain Howell was suffering from a severe headache, and retired to his berth to sleep it off, delaying the ship’s departure from Tacoma by several hours.

There was never an exact accounting of how many people boarded the Pacific at Tacoma and Victoria on her final voyage. Twenty passengers are known to have been booked aboard the ship at the last minute, their names forever lost, and witnesses later described miners climbing aboard her gangplank, and over her rails, until she was beyond reach; “Her deck black with people.” With her cabin and dormitory areas filled beyond capacity, passengers were bedded down in her saloon as well, and some sources claim that others slept on deck ~ although how that was accomplished on a rainy November night is not explained. She carried a cargo consisting of two thousand sacks of oats, ten tons of sundries, three hundred bales of hops, one hundred eleven hides, 31 barrels of cranberries, two cases of opium, eighteen tons of general merchandise, two buggies, six horses, and $79,220.00.

One might wonder if the tales of people struggling to board a third rate liner of no great repute on an unpleasant November day were created as human interest stories in the days after the disaster became known. One bit of evidence supporting the claims that the vessel was jammed was the experience of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Styles and their child. When Mr. Styles approached the Pacific’s agents to book tickets south for his family, he was quoted a fare of $10 for a first class cabin. He did not immediately secure passage, and when he returned the following day he was informed that, due to high demand, the asking price had gone up to $15. In an era when .10 per hour was considered a fair wage, the $5 price jump represented a considerable sum, but Mr. Styles paid it. His wife and child were both lost, and neither body was recovered.

Perhaps the best known passengers aboard were Dennis Kane and Richard Lyon, who discovered the Cassiar goldfields and incited the rush north. Their polar opposites were the unnamed miners who swarmed aboard the ship up until the last minute, presumably in a hurry to return south before the Canadian winter set in. They did not appear on the manifests, had no strong ties to their communities in Canada and so were not missed when they failed to return the following spring. In most cases, these men were not expected by friends and family in the south. So they vanished, forever, as did the 41 Chinese passengers who were on the manifest as a single entity; “41 Chinese.”

Fannie Palmer, a young Victoria socialite traveling to San Francisco for a round of visits, mentioned to some of her friends who came to see her off that she felt she was meeting them for the last time in this world. One might write this off as a newspaper fabrication , except that she expressed similar sentiments in a last-minute letter sent to an old school friend. Jane Palmer, her mother, commented to her acquaintance, newspaperman D.W. Higgins “I’m seeing the last of Fannie” as they watched the Pacific depart together. Fannie’s was among a handful of bodies recovered. In an incredible coincidence, she was swept a possible forty miles up the Washington coast, through the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and past the shore side home of her parents. She washed ashore on San Juan Island after a posthumous journey of over one hundred miles. Articles of her luggage also washed ashore in Canada and along the U.S. coast.

Francis Garesche, of The Garesche and Green Bank, and Wells Fargo Agent, boarded the ship as an escort to a $79,000 Wells Fargo shipment placed aboard the Pacific in Victoria. Garesche’s wife, Clara, was in England with their one year old son, Herman, while their other four children remained behind in Canada. Francis Garesche had recently completed a commercial structure in Victoria, the Garesche Block. He maintained close ties to San Francisco, where some of his children were born. D.W. Higgins saw him off, and from there he vanished from the record: neither of the two survivors knew him personally, or mentioned seeing him aboard the ship. Clara and Herman Garesche departed for home immediately upon learning of his death, arriving in NYC aboard the Algeria on December 6th 1875. A Garesche Street still exists in Victoria, as does the elaborate mansion of Francis’ business partner A. A. Green, at 1040 Moss Street. The Garesche and Green Bank failed in 1894, after which A. A. Green’s mansion became Government House. Since 1951 it has been the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. The Green mansion gives insight to the lifestyle enjoyed by Francis and Clara Garesche before the disaster. Garesche family photos, belonging to his son Arthur Garesche, born 1860 in Vulcanville, California, can be found in the Victoria Public Archives.

Actor and promoter Cal Mandeville departed on the Pacific with his wife, Bella, and their child. He was accompanied by his sisters, Alicia Thorne and Jennie Parsons, with whom he once performed onstage as The Pennsylvanians. Completing the travel party was his brother in law, Otis Parsons, and the Parsons’ child. Otis Parsons knew the dangers of ocean travel better than most. He was aboard the Prince Alfred when she was wrecked, and aboard the Los Angeles when she broke a shaft and was stranded – the very voyage on which Captain Howell of the Pacific behaved with exceptional heroism. The Parsons family were originally booked aboard the Dakota but changed their tickets to the Pacific and sailed with Jennie Parsons’ extended family. In an interview attributed to survivor Henry Jelly it was stated that during the disaster the Parsons child was crushed to death when the ship heeled and a man fell on him or her, and that Mrs. Parsons carried the corpse with her into a lifeboat that soon overturned.

There was even a celebrity spouse aboard. Mr. H.C. Victor was the husband of the (then) well known author, historian and folklorist Frances Fuller Victor (see http://www.ochcom.org/victor/)

Following his death, Mrs. Victor fell upon financial hard times and her career declined.

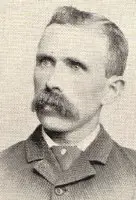

Henry Jelly, 22, had spent several months working as a surveyor on the Canadian Pacific Railroad and was returning to his home in Ontario. He would be swept 40 miles up the coast after the Pacific sank and, eventually, be rescued. Jelly’s traveling companion and fellow Canadian Pacific Railroad surveyor A. Fraser was not as fortunate.

Among the other passengers were Mr. and Mrs. Hellmuth, prominent citizens of Walla Walla. Mr Hellmuth was a successful merchant and they were commencing a tour of Europe. Elizabeth Moote was the married daughter of former Victoria Mayor turned newspaper editor James McMillan. She was returning to her husband in San Francisco following a family Christening. Former Washington Territory postal agent Fred Hard sailed, as did former Oregon State Legislator G.T. Vining.

No doubt the passengers hurried indoors as quickly as possible, as the Pacific departed under dark skies and in deteriorating weather.

The rotten liner barely made headway – witnesses on ships in the harbor described her as making awkward progress and showing a marked list. Her lights were visible from shore long beyond the point when they should not have been. Henry Jelly, one of the two survivors, testified that Captain Howell ordered all of the lifeboats along one side of the ship filled with water to counteract the list. By that action, he sealed his fate as one of the “villains” of the piece, but in truth, the commander of a single deck 900 ton vessel, with as many as 500 people crammed aboard it, that was showing stability problems and sailing into a mounting gale, was in an unenviable position. He corrected the list and, in his defense, had the boats been usable later that evening it probably would not have made a difference.

Around 10 pm, while at a distance of twelve to fifteen miles off the Washington coast, the Pacific rammed the sailing vessel, Orpheus, under the command of Captain Charles Sawyer. It was, by all accounts, not a major collision. The Orpheus lost some of her rigging, and a section of railing was carried away. It was later mentioned that Captain Sawyer’s wife had been so angered by the slight collision that she attempted to board the Pacific over her railing to confront the Captain. Captain Sawyer, fearing that the collision might have damaged the side of his ship resumed sailing in order to make shore and assess damages. The last the Pacific was seen from aboard the Orpheus, she had altered course and was following the sailing vessel towards shore.

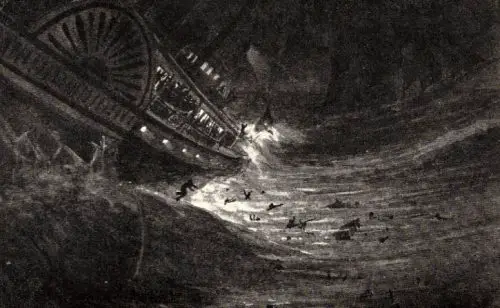

She did not last long. Despite the light impact, the Pacific began breaking up soon after the collision. At least one lifeboat was lowered, and swamped, during her brief remaining time afloat. Other boats were jammed with passengers and crew but could not be put over the rail, and some ten minutes after the accident, the Pacific broke into three sections and sank. Perhaps twenty survivors made it to rafts and floating debris, but over the next day all but two succumbed to exposure or were swept off by waves, including Captain Howell, who clung to a section of the hurricane deck with the larger of the two groups of survivors that came together in the water. Henry Jelly, who clung to the overturned lifeboat, a hen coop, and the roof of the liner’s pilot house, was found by accident, by the Messenger, a day and a half after the disaster. His tale of the Pacific rolling onto her side and breaking apart, after a demoralized panic among the passengers and crew, was initially greeted with some skepticism. Quartermaster Neil Henley was found nearly three days after the sinking by the search vessel Wolcott. His story reinforced that of Mr. Jelly in most particulars. Henley declared:

I was off watch and about 10 p.m. was awakened by a crash, and getting out of my bunk found the water rushing into the hold at a furious rate. On reaching the deck, all was confusion. I looked on the starboard beam and saw a large vessel under sail, which they said had stuck the steamer. When I first distinguished her, she was showing a green light. The Captain and officers of the steamer were trying to lower the boats but the passengers crowded in against their commands, making the efforts useless. None of the lifeboats had plugs in them. There were fifteen women and six men in the boat with me, but she struck the ship and filled instantly, and when I came up I caught hold of the skylight, which soon capsized. I then swam to part of the hurricane deck which had eight persons clinging to it. When I looked around, the steamer had disappeared leaving a floating mass of human beings, whose cries and screams were awful to hear…In a little while it was all over; the cries had ceased, and we were alone on the raft, the part of the deck on which was the wheelhouse. Beside myself, the raft supported the Captain, second mate, cook, and four passengers, one of them a young lady. At 1 a.m. the sea was making a clean breach over the raft. At 4 a.m. a heavy sea washed over us, carrying away the Captain, second mate, the lady and another passenger, leaving four of us on the raft. At 9 a.m. the cook died and rolled off into the sea. At 4 p.m. the mist cleared away and we saw land about fifteen miles off. We also saw a piece of wreckage with two men on it.At 5 p.m. another man expired and early the next morning the other one died, leaving me alone. Soon after the death of the last man I caught a floating box and dragged it on the raft. It kept the wind off, and during the day I slept considerable. Early on the morning of the eighth, I was rescued by the revenue cutter Wolcott.

Henley had been adrift for close to 70 hours. 1875 articles claim that Henley identified a vessel named the California as having been one of the ships Henry Jelly mentioned in interviews as having passed the dwindling group of Pacific survivors. I have not found this fact in the context of a direct quote and it may well be a newspaper fabrication. He outlived the Pacific by 69 years; Robert Belyk cites an obituary for him, with a Pacific reference, in the Tacoma News Tribune of March 14, 1944. He died in Steilacoom, Washington. A Neil Henly, a ship’s carpenter born in Scotland, in 1856, is shown in various editions of the U.S. Federal Census as residing in Steilacoom and Tacoma, Washington, with his wife, Marcella, and at least six children. The 1910 census shows Neil Henley (the only time the “ey” common to newspaper accounts and books was officially used) a ship’s carpenter, born in Scotland, in 1858, as being a resident of Mc Neil Island Penitentiary. The 1910 census is also the only one in which neither Neil Henly, ship’s carpenter of Steilacoom and Tacoma, nor his wife and family members appear. It seems probable that Henly and Henley were the same man.

Henry Jelly’ s story was told, widely, and with so many details added or subtracted by those who paraphrased it that it is more effective to distill the common details of the various accounts into a summary than it is to quote directly from them. He was awakened in his cabin by the impact of the collision, went on deck and saw the lights of the departing Orpheus, and returned to his cabin. He heard the sound of water rushing into the ship, returned to the deck and assisted in the firing of five rockets or blue lights. He described a panic on board, during which passengers and crew swarmed into all but one of the boats before they were swung out, making it impossible to launch them. He was dumped into the ocean from the same upset lifeboat as Quartermaster Henley. From his position on the overturned boat, he saw the ship’s funnel fall over as she rolled onto her port side, and then saw the Pacific split in half, with her superstructure breaking away as a third section.

This account seems to be the least elaborate, and therefore most likely to be accurate, of those attributed to Mr. Jelly. It was sent via telegraph, and many newspapers across the U.S printed it verbatim, in telegraphic style:

I took cabin passage aboard the Pacific from Victoria, leaving about a quarter past 3 Thursday, November 4, with about 250 people on board. The steamer ran all day against a southeaster. The crew was constantly pumping water into the boats to trim the ship.

The boats abaft the paddle boxes had no oars in them, but the others had.

Between 8 and 9 in the evening, while in bed, I heard a crash, felt a shock like she had struck a rock, heard something fall as if rocks had fallen on the starboard bow. The bell struck to stop, back, and go ahead.

Went on deck; heard voices say “It’s all right. We’ve struck a vessel.” Saw several lights at a distance but did not think they collided. Paid little attention; went back to cabin; noticed that the ship took a heavy list to port.

Went on deck to the pilot house; heard someone say “She is making water very fast.” The captain was coming out of his room. Asked him if there were any blue lights or guns; he said the blue lights were in the pilot house. Went and burned a fuse. Noticed that the engines were still working but there was no one at the wheel.

Went to the starboard side, forward of the paddle box where a number of men were trying to get a longboat but could not. Went to the port boat forward; helped five or six women into it; heard that the boats abaft the paddle box got away but did not see them.

She listed so much that the port boat was in the water. I was in that boat. Cut loose from the davits. The boat filled and turned over. Got on her bottom and helped several up with me. Immediately after the steamer separated. Broke in two fore and aft. The smokestack fell and struck our boat and the steamer sank.

Think about all women were in our boat. Fear they all drowned when the boat upset. This was about ten o’clock in the night. Not dark, nor the sea very rough, but there was a fresh breeze.

Afterward, left the bottom of the boat and with another man climbed on top of the pilot house floating near. Next morning got hold of some life preservers floating near, and with their ropes lashed myself and my companion to the house.

Saw three rafts. The first had one man on it; next had three men and a woman; could not tell about the other for the distance except that there were people on it.

Think we were thirty or forty miles south of Cape Flattery when the vessel sank. Passed the light on Tatoosh Island between four and five in the evening. I and my companion were on the pilot house all of Friday until about 4 a.m. when he died. The sea running very high all day, the water washing over us.

Soon after he died I sighted a vessel and heard the people on the other rafts calling but the vessel did not come near. Friday night there was but little wind until morning when the wind and sea rose. I was then within a mile of the shore of Vancouver Island. Sighted two vessels on the American shore which passed on. About ten o’clock in the morning Saturday the Messenger picked me up. (Signed) Henry Jelly.

Henry Jelly, was widely reported to have died soon after the disaster from the effects of prolonged exposure. Research by Robert Belyck has established that he lived well into the twentieth century, dying in 1930 in Canada. The man with whom he shared his raft was believed to be Mr. John “Jack” McCormack, who had taken $6000 out of the Cassiar gold fields in 1875.

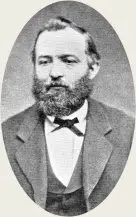

The Orpheus, in the meantime, ran ashore on Vancouver Island, near Cape Beale, in the early hours of the day following the collision and was a total loss, although her crew of twenty one, plus Mrs. Sawyer, survived. Captain Sawyer was accused, in some circles, of having intentionally wrecked the ship to “Conceal the evidence,” but the stranding and loss was certainly a coincidence. Sawyer did not believe that so light a collision could have sunk an ocean liner, and not knowing that the ship, and between 275 and 500 people were gone, would have had no reason to ruin his own craft and risk his own life. Friends later said, however, that the loss of the Pacific haunted him until his dying day. Captain Sawyer testified:

The Orpheus was steering about north, keeping close in to the land, with the wind from the southward, and blowing fresh with fine rain, the ship going about twelve knots. Her head yards were braced sharp up by the starboard braces, her main and after yards square, thus leaving the ship in such a position that she could be hauled offshore on a moment’s notice, if anything came in view. At 9:30 p.m. I left the deck in charge of a second mate, Allen I think his name was, with orders if he saw anything to starboard the wheel and keep her head to the northwest offshore.

I went below to consult the chart and had just seated myself at the table in my cabin with my oil clothes on, looking at the chart, when I heard the second mate tell the man at the wheel to starboard his helm. I looked up at the compass over my head and saw that the ship’s head was rapidly coming up towards the northwest. I immediately went on deck and asked the officer what was the matter, and he said that there was a light on the port bow; said it was Flattery Light. I told him it was impossible to have Flattery Light on that bow, and just then I saw the light on the starboard bow. I let the ship come up in the wind until she headed to the southward of west, and the after sails aback. My ship was now comparatively at a standstill, in just such a position as I would be if I were going to take a pilot on board. This brought the steamer’s light a little forward the starboard beam. I stood looking at her with my glasses. I did not think there was going to be a collision, but, as I looked and saw no change in the course of the steamer, I said to the second mate ‘She will be into us’ though I did not think she would, for I thought she would see us and keep off.

I made up my mind that she would hit us, and shortly afterwards she blew her whistle, and immediately struck us on the starboard side in the wake of the main hatch. The blow was a light one. She had evidently stopped her engines and was backing, and gave us a glancing blow, for she bounded off and again struck us at the main topmast backstays, breaking the chain plates, carrying away the backstays and bumpkin, main and main topsail braces, leaving me comparatively wreck on the starboard side. Before she blew her whistle my wife came on deck and stood by my side. We could plainly see her deck, from the pilot house to her bows, and not a soul was to be seen there as she passed the stern. I hailed her and asked her to stand by me, but she made no reply. My wife attempted to jump on board of her, and would, had I not grabbed her.

We drifted apart, and I gave my attention to my ship and gave orders to the mate to cut the lashings on the boats and to the carpenter to sound the pumps. My rail was broken from the fore rigging to the main rigging. The first report the carpenter made was that the ship was half full of water. I told him to take a light and go down the fore hatch and see. In the meantime I found there was no water in the hold. I then gave orders to the mate to never mind the boats, but to take all hands and secure the backstay and repair damages. All my starboard braces had been carried away with the blocks, etc.

Now, while I was attending to the condition of the ship, it certainly took from ten to fifteen minutes, and during that time I never looked after the steamer, neither did anyone else I know of. We were all busy attending to our own necessities. When, after I found that I was not seriously damaged, I looked for the steamer I just saw a light on our starboard quarter, and when I looked again it was gone. There has been a great deal said about the crying and screaming of the women and children aboard the steamer. Not one sound was heard by anyone on my ship, neither was anyone seen on board of her. Neither did anyone on my ship think for a moment that any injury of any kind had happened to the steamer, for at 1:30 that night, as the sailors were furling the spanker, they commenced to growl, as sailors will, about the steamer, after running us down, to go off and leave us in that shape without stopping to inquire whether we were injured or not.

One detail of Sawyer’s account does not ring entirely true. Even at full speed, in the ten to fifteen minutes it took the Pacific to break up and founder, the Orpheus must have been fairly close at hand when the other ship sank. What of the six blue lights, or rockets, Henry Jelly allegedly helped fire from the Pacific? My own belief is that Sawyer did not see them. My rationale? Sawyer was not a beloved captain. He referred to his own men as ‘scoundrels’ and was so remote a shipmaster that he was not sure of his own Second Mate’s name (James G. Allen, former First Officer of the Pacific) and would see his crew turn on him in court and in the press. They accused him of negligence, They accused him of being a drunkard. They accused him of actually being the man at the wheel at the time of the collision and intentionally running the Orpheus across the path of the oncoming Pacific in order to halt her to ask for a position report. And, they accused him of either accidentally destroying his own ship (while drunk) or intentionally destroying it to remove evidence and divert attention. But, apparently, none of his men accused him of ignoring rockets or flares fired from the sinking Pacific, which surely they would have done had it happened.

Captain Sawyer was born in Gloucester Massachusetts in 1839, and died October 6, 1894, at Port Townsend Washington. A year and a half before his death, in January 1893, the anchors and two hundred twenty fathoms of chain were recovered from the wreck of his former command, the Orpheus, by the Moscotte, and taken to Victoria.

Fragments of the Pacific, including a portion of her bow that apparently snapped off during the collision and became entangled in the Orpheus’ rigging were widely scattered along the Washington coast, and on Vancouver Island. They were reportedly so rotten that they could be picked apart by ones fingers. The ornamental eagle from atop her pilot house survived for a time afterwards, and may still exist somewhere in Canada. A few bodies, perhaps as many as twenty, were recovered, but the majority of those who went down with the Pacific were lost at sea forever.

The Coroner’s Jury, at Victoria, gave the following verdict, regarding the death of passenger Thomas Ferrill:

That the said steamer, Pacific sank after a collision with the American ship Orpheus off Cape Flattery, on the night of November 4th, 1875; that the Pacific struck the Orpheus on the starboard side with her stem a very light blow, the shock of which should not have damaged the Pacific had she been a sound and substantial vessel; that the collision between them was caused by the Orpheus not keeping the approaching Pacific’s light on her port bow as first seen, by putting the helm hard to starboard and unjustifiably crossed the Pacific’s bow; that the watch on the deck of the Pacific at the time of the collision was not sufficient in number to keep a proper lookout, the watch consisting of only three men, namely, one at the wheel, one supposed to be on the lookout, and the third mate, a man of doubtful experience; that the Pacific had about 238 passengers on board at the time of the collision; that she had five boats the utmost carrying capacity of which did not exceed 160 persons; that the boats were not and could not be lowered by the undisciplined and inexperienced crew; that the captain of the Orpheus sailed away, after the collision, and did not remain by the Pacific to ascertain the damage she had sustained.

The American investigation, held in San Francisco, was widely considered to be a whitewash. It was held behind closed doors, and was conducted by Hull Inspector Captain Bob Waterman. They concluded that the Orpheus bore most of the blame for the disaster and that the Pacific did not sink because she was rotten per se, but because of a chance meeting between a lightweight steamship hull that would have crumbled when brand new, and that of a staunch sailing vessel.

Goodall, Nelson and Perkins changed its name to the Pacific Coast Steamship Company in 1877, and continued their practice of offering cut rate fares on extremely old ships into the Twentieth century. Co-owner George Perkins later served as a U.S. Senator, from 1893 until 1915.

Although the disaster was not a major media event beyond the West Coasts of the United States and Canada, it had a regional impact akin to that of the Titanic, and did not gradually fade away from the public mind as did so many other shipwrecks. 29 years after her loss, Canadian folklorist D.W. Higgins wrote this account of the disaster, from the position of one who had been aboard the ship on the last day and knew a number of the victims. It reflects, beautifully, how more than a generation after her loss, the Pacific continued to haunt the Northwest.

The unhappy tale I have undertaken to write revives recollections which, were I to consult my own private feelings, I would gladly allow to remain undisturbed in the misty records of the past. But he who takes the role of faithful chronicler of historical events should not shrink from performance of a task, however distasteful or painful it may be to him or those whose reputations may suffer by the narration. Sentiment should not be allowed to interfere with the duty of the historian, even though dead and buried animosities be called back to life and old wounds opened and made to bleed afresh. I propose this morning to tell the story of the loss of the steamship Pacific, which occurred twenty-eight years ago. I think I can fairly claim that, with the exception of the two men who survived the wreck, three is no person now living who is in a position to give as correct a narrative of that awful tragedy and the circumstances that led to it as myself. There has never been a doubt in my mind that those circumstances were preventable- that had the crudest precautions been adopted and the commonest decencies of life observed, the disaster would never have taken place. With this brief introduction I shall plunge at once into the task and drawing aside the veil shall proceed to tell the story of that lamentable disaster, with all its tragic and heartrending details.

The steamship Pacific was built in New York in 1851. She was less than 900 tons burthen, and fifty years ago was considered a ‘crack” vessel fitted with all the (then) modern improvements. Today it is safe to say that no vessel of her class would receive a permit to put to sea with passengers. She might be tolerated as a freighter, but it is doubtful if a crew could be found to man her. If such was her condition when the Pacific first took the water, what must have been her state when, twenty five years later, under the command of Captain Jefferson D. Howell, she left Victoria harbor on her last voyage, loaded to the gunwale with freight and so filled with passengers that all the berth room was occupied and the saloons and decks were utilized as sleeping spaces? I do not believe that anyone, not even the agents or officers of the steamer, knew the exact number of persons she carried on that fateful voyage. There was a brisk competition between the Goodall & Perkins Line, to which the Pacific belonged, and the Pacific Mail Steamship Co., which latter company had shortly before secured a lucrative contract for carrying the mails between Victoria and San Francisco. Fare on the Pacific was reduced to $5, and if a party of three or four applied for tickets they were taken at $2.50 a head.

On the morning of the 4th of November, 1875, having business with a gentleman named Conway, one of the passengers, I was on the wharf before the hour which the steamer was advertised to sail- 9 a.m. I found the boat so crowded that the crew could scarcely move about the decks in discharge of their duties. I have always contended that the passengers numbered at least 500. This belief has been disputed; but it has never been successfully disputed. The agents’ list showed that only 270 passengers were booked at Victoria, but there was a large list from Puget Sound, and it was admitted that scores took passage without having secured tickets, competition being so keen that some were carried for nothing to keep them from patronizing the opposing line. Besides, small children paid no fares, and were not counted.

The morning was dark and lowering. Heavy clouds moved slowly overhead. A fall of rain had preceded the coming of the sun, but there were no signs that indicated worse weather than is usual in this latitude in the fall of the year. I think I must have known at least one hundred of the persons who took passage that day, and who twelve hours alter found a common grave in a

“Dreadful and tumultuous home

Wide opening and loud roaring still for more.”Captain and Mrs. Otis Parsons and child, with Mrs. Thorne, a sister of Mrs. Parsons, were amongst those to whom I said farewell and wished bon voyage.The Captain had sold his interest in Fraser river steamers for a sum exceeding $40,000.00 in gold, and it has always been a mystery what became of the money. After the ship had gone down and it was known beyond a doubt that Parsons and his family were lost, the most diligent enquiries by relatives failed to disclose the whereabouts of the treasure. The banks could furnish no information. Some ventured the opinion that the gold was in the stateroom and went down with him, but the hackman who took him and his baggage to the wharf said that there were no heavy packages among it. Had the gold been there, its weight would have betrayed its presence as more than one man would have been needed to lift it. Mrs. Parsons had been on the stage. She came to San Francisco in 1856 as the contralto in a group known as The Pennsylvanians. She had a voice of great sweetness and power and was a decided favorite with all lovers of good music. Parsons was attracted to her by her fine acting and singing, and married her while she was a member of the Fanny Morgan Phelps Company, which held the boards at the Victoria Theatre for a long time.

Having said goodbye to Parsons and his family, I reached with difficulty a place where Miss Fannie Palmer, youngest daughter of Professor Digby Palmer, stood. This young lady was a bright and lovely member of Victoria society. She was most popular, and naturally attracted a large circle of admirers. By a number of these she was besieged when I advances to say farewell. Her fond mother was in the group that surrounded the fair girl, whose sweet face was more than usually animated in anticipation of the round of pleasure that awaited her upon arrival in San Francisco.

Every class, every nationality, every age were assembled on the deck of that doomed vessel. The last hands I grasped were those of S.P. Moody, of the Moodyville Sawmill Co., and Frank Garesche, private banker and Wells, Fargo & Co.’s agent. As I descended the gangplank I met a lady with a little boy in her arms. The way was steep and I volunteered to carry the little fellow aboard. He was handed to me, and I toiled up the plank and delivered him to his mother when she, too, had gained the deck. The wee, blue-eyed boy put up, his lips to be kissed, and waved his little hands as I turned to go, and then mother and child were swallowed up in the dense throng, and I saw them no more forever.

The ship, as I have said, was billed to sail at nine o’clock. She did not sail until nearly an hour later. The same thing happened at Tacoma the day previous. The steamer was advertised to leave at noon. She did not leave until evening. The captain, who was in bed, had given orders that he should not be disturbed until he awoke. And so a mail-carrying vessel, with steam up and a big crowd of passengers anxious to get on, was detained because the Captain had a headache and must not be disturbed! It was nearly ten o’clock when Captain Howell appeared on the bridge at Victoria and the order was given to cast off. Had that order been given at nine o’clock, in all human probability the ship would have escaped the peril which awaited her, and this dismal chapter would never have been written. Some people will persist in attributing disaster and sickness and ill-fortune to the Divine will, but if the whole world were to cry out that the Pacific was lost because God willed it, I should say that the vessel went down because the most ordinary precautions for safety were violated by her officers. I do not think that the captain realized the importance and gravity of the duties he had undertaken to discharge. I do not believe he ever reflected that in his hands were placed the lives and property of several hundreds of his fellow beings and that upon his judgment, sobriety and care depended their safety.

The Pacific was a bad ship, and an unlucky one. She had been sunk once before, and for two years previous to the breaking out of the Cassiar gold fever had been laid away in the Company’s “bone yard’ in San Francisco, from which she was taken and fitted up to accommodate the rush of people to the new gold fields. She was innately rotten, but the paint and putty thickly daubed on covered much of the rottenness, as paint and powder hide the wrinkles and crow’s feet of a society belle, and scarcely anyone was aware of the ship’s real condition. A month after she had gone down portions of her frame that came ashore at Foul Bay were so decayed that you could pick them to pieces with your fingers. The wood about the bolt heads was gone and the bolts played loose in their sockets. The vessel was not in condition to withstand the impact of a severe shock; but had the officers discharged their duty there would have been no shock and no lost vessel, on that voyage, at least.

As the vessel swung off, the multitude on the wharf gave three rousing cheers to speed departing friends on their way. The response was loud and hearty, and hands and handkerchiefs were waved and last messages exchanged until the vessel had disappeared around the first point. A belated Englishman, who had passed the previous night in a wild revel, and who had taken a ticket by the Pacific was the “last man” on this occasion. As the vessel passed out, the belated one appeared on the wharf with his hand bag and a steamer trunk. He shouted and signaled, but all to no purpose. The boat kept on her way, and the man danced up and down in his rage. Then he sat down on his trunk and cursed the boat and all its belongings. His profanity was awful to hear and quite original. As it appeared to do him good, no one interrupted him. When I left, he was still cursing. If the man read the papers five days later he must have thanked his stars that the Captain did not put back to take him on board, and no doubt he recalled all his naughty words.

On the corner of Government and Fort Streets, as I passed along a few minutes later, I saw Mrs. Digby Palmer standing. She was gazing with glistening eyes towards the outer harbor. Where the Rithet Wharf now stands there was on the shore quite a grove of tall forest trees. Above the tops of these trees the smoke of the departing steamer was rising in great black billows and losing itself in space. It was this smoke Mrs. Palmer was watching. As I approached, she exclaimed: “I’m seeing the last of Fannie!” Alas! How true it was. The poor mother’s fond eyes had seen the last of her dear child in life,. The body of that child, after being the sport of the cruel waves for ten days, was borne in the tide past her Victoria home and laid on the beach at San Juan Island almost within sight of the house she had left a short time before so full of life and happiness.

It was Thursday when the steamer sailed. On Friday, Saturday and Sunday heavy storms prevailed, and the telegraph lines went down. Until Monday afternoon there was no communication by wire with the outer world. About noon on the afternoon of the 8th of November, Mr. W.F. Archibald, who was chief operator at Victoria received this message from Port Townsend:

A ship has arrived here with a man named Jelly aboard, who was picked up Saturday floating on a piece of wreckage off the entrance to the Straits. He says the steamer Pacific sank last Thursday night, and he fears all on board were lost but himself.

Then the wires went down, and no further information could be obtained through that medium. An hour or two later, the steamer North Pacific came in from Puget Sound. On board her was Henry F. Jelly, the rescued passenger. The whole town rushed to the wharf. I was fortunate in interviewing the man, and from him learned that the Pacific ran into a sailing ship while off Cape Flattery, about ten o’clock on the night of the day on which she sailed from Victoria, and sank in ten minutes. The greatest consternation prevailed. The officers lost their presence of mind (if they ever had any) and the crew were too intent in endeavoring to ensure their own safety to pay attention to the passengers. In the crush Mrs. Parsons’ child was torn from her arms and killed, and the last Jelly saw of the bereaved mother was when she stepped into one of the boats still pressing her dead child to her breast. This boat was swamped in lowering and all who had entrusted themselves to it were lost at the side of the fast-sinking ship. Some of the life (death?) boats were found to have been filled with water to steady the ship, and before the water could be run off the passengers and crew crowded in and would not get out. So, all attempts to lower the boats had to be abandoned. A rush was made for the life preservers. The number available was not sufficient, but all the bodies afterwards recovered wore life preservers. All this time, the vessel was sinking, and her rail was almost even with the water when several of the male passengers leaped overboard and drowned. Absolutely, beyond the lowering of the one boat that was swamped at the side, nothing was done to save a single life. All was confusion and despair….and so they remained helplessly huddled together while death came on with ever shortening steps. Presently, the ship lurched, and every beam seemed to crack. A cry of despair ascended from the doomed company as the decks opened before the combined pressure of air and water with a great roar, as though a thousand boilers had burst simultaneously. The next moment the Pacific sank beneath the waves and the sea was dotted with drowning men and women.

Jelly, with three others, managed to secure a hen coop, and floated away with the tide. In a few minutes the last

“Solitary shriek, the bubbling cry

Of some strong swimmer in his agony”died away, and Jelly and his companions were afloat and, so far as they knew, alone on that wild waste of water. The night was intensely dark and the waves frequently broke over the wreckage on which the poor men were. Before daylight two had been washed away, and when the sun came up the third man went out of his mind and before evening leaped into the sea and disappeared. Two days after the disaster, Jelly was picked up by a passing vessel and taken to Port Townsend. From that port a revenue cutter was dispatched to the scene of the wreck, and on the way out of the Straits, Neil Henley, a quartermaster of the wrecked vessel, was found floating on a piece of wreckage and saved. He reported that Captain Howell, the second mate, the cook, and four passengers (one a young lady) were on the wreckage with him when the ship first went down, but all perished one by one until only he remained. The young lady, from the description, was believed to be a Miss Reynolds of San Francisco who was returning home from a visit to friends at the Dockyard, Esquimault. Once she was washed off the raft, and the second mate plunged in and rescued her. She resumed her place on the raft, but seemed to lose all hope. Gradually, her strength departed and she lay motionless on the fragment until a wave washed her away, her heroic rescuer soon following.

From Victoria, a steamer was dispatched to the vicinity of Cape Flattery. She returned in a few days with four bodies- three men and a woman. The men were identified. One was a merchant from Puyallup, and two were members of the Pacific’s crew. The rescue of Henley cleared away much of the mist that obscured Jelly’s statement. Henley was asleep in the forecastle when the crash came. He said the water flowed in at the bows of the steamer with a rush. He was awake and on deck in an instant, and saw a large ship off the forward bow. This ship afterwards proved to be the American ship Orpheus, bound for Puget Sound in ballast. She was commanded by Captain E.A. Sawyer, who made no effort to assist the Pacific, but stood off for Vancouver Island, and a day or so later his vessel was hopelessly wrecked in Barclay Sound. His excuse for his inaction was that he believed his own vessel to be sinking, and he explained that he stood across the Pacific’s bows, and so caused the collision, for the purpose of speaking to her and learning his whereabouts. He always claimed that had there been a proper lookout on the steamer three would have been no disaster. H.M.S. Republic passed out of the Straits on the night of the wreck and it is said by some of the sailors that they reported to the captain that blue lights were burning on the port side, but that no attention was paid to the report.

(Author’s Note: The significance of that last anecdote is obscure. One wishes Higgins had filled it out with a bit more supporting detail. Were the blue lights supposed to be those of the wrecked Orpheus? Were they the rockets Jelly reportedly helped fire from the Pacific? What, exactly, was their link to the Pacific disaster?)

The woman whose body was brought in was a tourist who was returning to San Francisco. About ten days after the disaster the body of Miss Palmer was brought from San Juan Island and buried during a heavy fall of snow, which blocked with great drifts and heaps the road leading to the cemetery- nature had sent the dead girl a winding sheet. In spite of the storm, the cortege was one of the largest ever seen in Victoria, so great was the sympathy felt for the father and mother of the bright young spirit whose light had been so untimely quenched.

As the days wore on, other bodies came ashore and were either brought to Victoria or interred where found. At Beacon Hill, ten days after the wreck, I saw the body of Mr. Conway, whom I had gone to the wharf to see on the morning the steamer sailed, rolling in the surf. The body was easily recognized. When the ship sailed he had a large sum of money in his possession, but when he was picked up everything of value was gone.

One day some Beechy Head Indians arrived in the harbor in a canoe, towing another canoe in which was the body of a large man. The body was recognized as the remains of J.H. Sullivan, the Cassiar Gold Commissioner, who sailed with high hopes of soon being with his friends in Ireland, and spending the Christmas holiday with them. In his pockets were found a considerable sum in drafts and gold, a gold watch and chain, and a pocket diary. In the diary, evidently written just before the unfortunate gentleman retired to his cabin, was this entry:

Left Victoria for old Ireland on Thursday, 4th, about noon. Some of the miners drunk; some ladies sick; feel sorry at temporarily leaving a country in which I have lived so long; spent last evening at dear old Hillside.

About a month after the ship had gone down, and when the first burst of grief had been replaced by a feeling of resignation, and while the shores were still patrolled for many miles in the hope of finding more bodies, a man walking along the southern face of Beacon Hill observed a fragment of wreckage lying high and dry on the beach. Upon examination it proved to be part of a stateroom stanchion or support, and on its white surface were written in bold business hand, in pencil, these words:

S.P. MOODY. ALL LOST

The handwriting as identified as that of S.P. Moody, the principal owner of the Moodyville sawmills, who was a passenger. It is supposed that when he found the ship was going down and no hope remained of saving his life, Mr. Moody wrote this message from the sea on the stanchion in the faint hope that it might some day be picked up and his fate known. This hope was not in vain, and I believe the piece of wreckage with the inscription upon it is still cherished by the Moody family.

Inquests held upon the bodies that were found placed the blame on the Orpheus for crossing the steamer’s bows and so causing the collision. The inefficiency of the watch of the steamer was condemned, and the condition of the boats was denounced, but nothing ever came of the verdict The owners of the boats were never prosecuted, and the officers were all dead. The families who were bereft of their breadwinners were not compensated for their loss, but after the lapse of these many years the occurrence and its accompanying horrors are still remembered by those who lost their friends or who were active participants in the after events.

How many hearts were broken in consequence of the disaster will never be known. Such unfortunates usually suffer in silence. I knew of one case where a young and industrious mechanic, whose sweetheart went down with the wreck, was never known to do a days work afterwards. When the first paroxysm of grief had passed, he was accustomed to walk listlessly along the water front and accost the master of every vessel that came in from the sea with inquiries as to whether any more of the Pacific’s people had been rescued. The reply was always negative, and he would walk off with a dejected air. Finally he went away, and probably died in some lunatic asylum or hospital. About fifty families were broken up and scattered, and many came upon the public for maintenance. There were two suicides at San Francisco in consequence of the disaster, and there were many instances of actual distress of which the public never heard. In all their details the circumstances attending the loss of the Pacific are among the most heartrending that ever came under my notice.

I have often narrated the dreadful story of the loss of the Pacific to friends who had heard only a vague account of it, and on several occasions as I concluded the narrative, I have been asked which incident of the many pathetic ones connected with the wreck dwelt most in my mind. In other words, which of the occurrences that led up to the sinking impressed me most. I have always replied that, sweeping aside every consideration of sympathetic interest in the fate of many acquaintances who were rushed into eternity in an instant, as it were- forgetting for a time the awful sensations those on board the ship must have experienced when the truth was forced upon them that they were beyond human help and that the sun had set forever upon their earthly careers- I say I have always replied that the one picture which presents itself to my mind when I recall the awful event is that of the bonnie little blue-eyed boy to whom I said farewell as the gang plank was drawn in. I had never seen him before- he was neither kith nor kin of mine- but whenever I think of the going down of the Pacific his sweet face appears to me- sometimes as I last saw it; and again wearing an expression of keen anguish and horror, the bright eyes filled with tears and the hands held out in a vain position to be saved from an impending doom. Since I sat down to write this sad story he has been with me every moment of the time; and once I thought I heard him repeat what I have often in the silent hours of the day or night imagined I heard him say: “You placed me in this coffin; cannot you help me out?” Alas! If I had but known.

Pacific Passengers

Known to have been aboard, November 4th, 1875.

First Class

Allison, Mr. T.

Ammiss, Mr. William

Atkins, Mr. E.P.

Bird, Mr. George

Bryson, Mr. George

Cahill, Mr. J.

Canty, Mr. P.

Champion, Mr. William.

Chapman, Mr. P.I.

Chisholm, Mr. C.

Cline, Mr. H.

Cochrane, Mr. .John

Cochrane, Mr. Richard

Congdon, Mr. J.

Conway, Mr.

Creden, Mr. J.

Crowley, Mr. J.D.

Davidson, Mr. C.B.

Davidson, Mrs.

Doyle, Mr. J.W.

Fairbanks, Mr. C.B.

Ferrell, Mr. J.T.

Ferry, Mr. W.J,.

Fitzgerald, Mr. J.

Foster, Mr. Adam

Foster, Mr. J.

Frazer, Mr. A.

Garesche, Mr. Francis.

Gretz, Mr. B.F.

Gribell, Mr. G.

Hard, Mr. Fred.

Haverly, Mr. John

Haverly, Mrs.

Hellmuth, Mr. J.

Hellmuth, Mrs.

Herne, Mr. George

Hudson, Mr. R.

Hurlburt, Mrs.

Jaynes, Mr. R.T.

Jelly, Mr. Henry

Johnston, Mr. .J.F.

Journeaux, Mr. G.

Kane, Mr. Dennis

Keller, Mr. H.

Keller, Mrs. Lizzie

Keller, child

Kenalley, Mr. John

Kennedy, Mr. J.

Lang, Mr. A.

Lawson, Mrs.

Layzelle, Mr. W.

Lee, Mr. John

Lennings, Mr. James

Lyon, Mr. Richard.

Mahon, Mrs.

Mahon, child

Mandeville, Mr. Cal

Mandeville, Mrs. Bella

Mandeville, child

Maxwell, Mr. William

McIntyre, Mr. D.C.

McLanders, Mr. J.

McLaughlin, Mr. J.

McCormack, Mr. John

McPherson, Mr. O.

Meyer, Mr. F.E.

Miles, Mr. C.N.

Moody, Mr. Sewell .P.

Moote, Mrs. Elizabeth

Morton, Mr. George.

Nichleson, Mr. S.

Otway, Mr. A.B.

Palmer, Miss Fannie

Parsons. Captain Otis

Parsons, Mrs. Jennie

Parsons, child.

Pettier, Mr. J.

Polley, Mr. William

Pooley, Mr. Edward H.

Powell, Mr. William

Power, Mr. William

Purdary, Mr. William

Rainey, Mr. A.L.

Reynolds, Miss A.

Robbins, Mr. A.

Robinson, Mr. T.J.

Sampson, Mr. John

Shephard, Mr. Edward

Skippon, Mr. George

Smith, Mr. Charles.

Smith, Mr. Thomas

Somers, Mr. C.

Somers, Mr. M.

Styles, Mrs. S.

Styles, child.

Sullivan, Mr. J.H.

Tarnett, Mr. John

Thompson, Mr. J.

Thorne, Mrs. Alicia

Todd, Mr. John G.

Turnbull, Mr. Richard

Victor, Mr. H.C.

Vining, Mr. J.T.

Waldron, Mr. Richard.

Waldron, Mr. W

Watson, Mr. John

Webb, Mr. James

Webbs, Mr. Isaac.

Webster, Mr. S.J.

Wills, Mr. William

Wilson. Mr. M.

Wood, Mr. V.

Young, Doctor.

The Rockwell and Hurlburt Equestrienne Troupe. They appear on the manifest under this group name, but I have not determined the names of the six members aboard.

20 passages were sold aboard the ship at Victoria to passengers whose names were not recorded.

Second Class. No manifest survived, but among the second class passengers were:

41 unnamed Chinese.

Pacific Crew

Howell, J.D. Captain.

McDonough, A.H. First Officer

Wells, A. Second Officer

Lewis, J.M. Third Officer

Houston, H.F. Chief Engineer

Bassett, D.M. First Assistant Engineer

Coghlan, A.J. Second Assistant Engineer

Hyte, O. Jr. Purser

Bigley, T.H. Freight Clerk

FIREMEN

Lestrange, James

Manders, Richard

O’Neil, James

_______unknown.

COAL PASSERS

Clancey, William

Palmer, Frank

Norris, Charles

Powers, Richard

OILERS

Elwell, Frank

Lestrange, Thomas

Errickson, R. Carpenter

Norris, Henry A. Watchman.

SEAMEN

Daley, John

Fairfield, W.

Henley, Neil

Guinn, Lawrence

Jamieson, Peter

Kerby, Thomas

Moore, Patrick

Sherry, John

Wilson, William

______ unknown.

STEWARDS

Jackson, H.

Martin, John

McNicols, S.

Minow, Sarah. Stewardess

COOKS

Holdsworth, J.M.

Miles, S.

Whiting, C.H.

Molloy, Thomas. Baker

Menaimo, Robert T. Porter

PANTRYMEN

Bell, Richard

Herbert, C.B.

Monroe, Daniel

WAITERS

Eisenor, Charles

Clare, Oscar

Hardie, John

Johnson, James

McGinnis, Jmaes

McMerim, Luke

Meza, J.C.

Walters, Andrew

York, Alfred