Lest We Forget Part 2

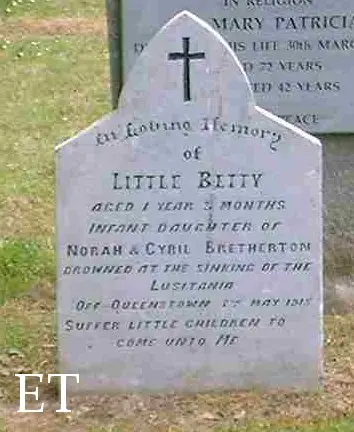

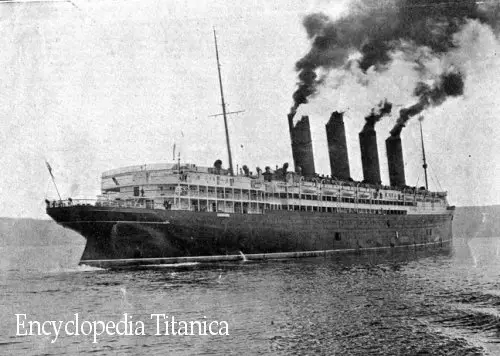

The second part of Lest We Forget, the human side of the Lusitania disaster.

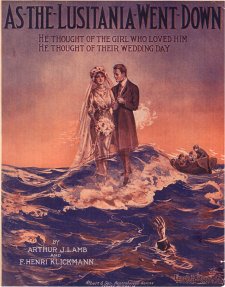

AS THE LUSITANIA WENT DOWN.

The sun was sparkling brightly

upon the ocean foam,

The Lusitania, speeding fast,

was very nearly home.Then came the blow so sudden

that pierced the vessel’s heart.

But while the crowd surged o’er the deck

a young man stood apart.He stepped into a lifeboat,

but ere it left the deck,

he saw a woman and her child

upon the sinking wreck.“Come, take my place”

he told her, and as she stepped inside,

he thought again of those he loved

and like a hero died.He thought of the girl who loved him.

He thought of their wedding day,

as he looked on the angry ocean

eager to seize its prey.He thought of his poor old mother

in a little southern town.

And sadly sighed “thy will be done”

as the Lusitania went down.Arthur J. Lamb and F. Henri Klickmann

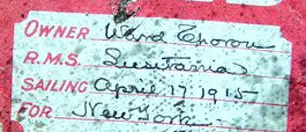

Luggage Label from the Lusitania’s final completed voyage.

Among her passengers were several who would be aboard the May 1 crossing, including W.S. Hodges; Beatrice Witherbee; Charles Tilden Hill and William Pierpoint.

|

| Francis Luker (Daily Sketch) |

The Lusitania was probably not on survivor Francis Luker’s mind on the afternoon of July 17th 1917. Luker, one of the heroes of the disaster, was more concerned with the details of his job as a letter carrier and with the midsummer heat than with his brush with infamy two summers before. He, of course, had no way of knowing that by 5PM he would be dead.

Francis Luker’s 1915 account of the disaster seems full of fanciful details, yet enough of it rings true or corresponds to what is known from other, less flamboyant sources to warrant inclusion:

During the voyage, I picked up with two young fellows with whom I shared a berth and all three traveled together. My two friends went below to get a nap, but I stayed on deck. About 2:30, p.m., as I was standing in the covered alleyway on the third class deck, the periscope of the German submarine was seen about 140 yards ahead…. The noise of the explosion was as loud as a big gun. Smoke and steam came up from the side of the ship in clouds.

The passengers all rushed over to the side of the ship to see what happened, and the lurching of the great wounded liner threw them all in a heap. Another violent lurch of the ship threw hundreds of people into the sea. I held onto a piece of iron fixed to the woodwork on the deck and was thus able to save myself from being away as the people were thrown past me.

I made my way to the second-class cabin to see if I could find a lifebelt, and, passing by the nursery, I noticed a little baby inside which had evidently been left there while the mother went to look for help, intending to come back again and fetch the child. I went forward to get hold of the child, but as I did so, the ship gave another terrific lurch and the door of the nursery was jammed tightly so that I was unable to save the child.

Unable to find a lifebelt, I made my way back to the second-class deck, where the crew were making attempts to launch some of the boats. Owing to the heavy list which the ship had taken this operation was most difficult, and the boats had to be swung so far out in order to avoid the ship, that it was most difficult to get the people into them. The first boat was too full to take me. Another was capsized through the ropes breaking so that the passengers were thrown into the sea. The boat was afterwards righted and the people were got back into it. The list of the ship was so great that I had to take a tremendous jump, which I successfully accomplished. I then grabbed a boat hook and pulled the boat in nearer to the great liner, which more passengers were able to get into it.

It was then that I managed to save Mrs. Wickings-Smith’s baby. She was trying to get into a boat with her baby, but they were holding her back, when I shouted to her to throw the baby to me, which she did. I caught the child, and handed it over to the care of some of the other occupants of the boat. I also caught another child safely, but had no idea whose it was. Mrs. Wickings-Smith was fortunately saved, but I had no idea until two or three hours later.

Before reaching land I changed boats five times, in order to leave more room for wounded passengers and women. One boat that I had got into had a defective plug and it was nearly waist deep in water. The first boat I was in was so close to the ship that they had to hold on to the wireless masts and push the wires away in order to prevent the boat being dragged down by them when the liner sank. She went down with very little suction, but when the boilers exploded, the passengers were smothered in soot and looked like n……s.

After the ship had disappeared, the water all round was just as if it was boiling and everybody thought that their last moments had come. However, we managed to get safely away from the whirling waters and started to render much assistance as we could to other who were still in the water.

Commander Jones was in charge of the boat in which I was finally rescued, and the boat became so full that we to refuse to take any more on board. I was able to render assistance to a lady, Miss Leipold, who escaped from the ship but had both legs injured. She came alongside the boat, and I reached out my hand to her, and for some time towed her along in this manner, afterwards having to grip her by the shoulder when she became exhausted. Eventually, they managed to make room for her in the boat by getting some of the men to lie down in the bottom.

And so things went on in this way until were sighted by a fishing smack and were taken aboard. About 100 from the different boats were got on board this vessel. After we were safely on board we could just discern smoke of the other vessels which were coming to our assistance. We remained on the trawler for about an hour during which time the sailors did everything they possibly could for our comfort, attending to the wounded and giving them whiskey, etc… We were then transferred to the paddle-steamer “Flying Fish” and taken to Queenstown. We arrived at Queenstown about 11:30 pm or nine hours after the Lusitania sank.

Luker returned to Saskatoon by way of NYC, aboard the Orduna in mid September 1915. He resumed his job as a letter carrier, and for the next two years lived quietly. He did not marry, and had no immediate family in Canada. His tragic end was such that decades later it was featured in a New York City newspaper profile. If ever a death can be deemed ironic, Francis Luker’s certainly was:

|

|

Phyllis Wickings-Smith was, by Lusitania standards an exceptionally fortunate woman; both her husband and her daughter, Nancy Eileen, were saved, Nancy being one of only four infants to survive the disaster. The Wickings-Smith party was comprised of Cyril Wickings-Smith, his wife Phyllis, their daughter Nancy and his brother Basil. Basil’s wife Beatrice, who did not sail, was Phyllis Wickings-Smith’s sister. She was not as fortunate as Phyllis, for Basil was lost in the disaster. From the Prichard letter collection (Imperial War Museum) and an account by Gertrude Adams, it is known that Basil Wickings-Smith managed to go below decks for life preservers without being trapped. Phyllis lived less than five years after the Lusitania tragedy, dying January 19, 1920. Cyril, her husband, died just short of the 50th anniversary, on April 3, 1965. Nancy Wickings-Smith Woods, the infant saved by Francis Luker lived until May 1993.

Left: Cyril Wickings-Smith, Right : Phyllis Bailey Fenn

Courtesy of Richard Woods

|

| Lusitania Officers Left to right: Arthur Rowland Jones, Albert Bestic, John Idwal Lewis. |

John Idwal Lewis started his sea-faring career in sail. The native of Portmadoc, North Wales was first signed aboard a three-masted bark where he remembered receiving a daily ration of a pound and a pint- eight ounces of butter, marmalade and sugar. He would also add that they gave him a pint of limejuice to ward off scurvy, but he never complained. Since he was slender and only stood about 5’6 in height, it was easy for him to work in tight places. In 1912, he finally went, as he put it, “in steam,” on the Moss Line and the Blue Funnel Line. The following year, he earned his master’s certificate.

He joined Cunard in September 1914 as intermediate third officer and a month later he was assigned to the Lusitania, and he would remain with her until the end.

Recalling his duties, he stated:

“There is a daily inspection on all the ships that I have been in this line, at half past ten. I used to attend on them everyday. I attended the whole of the ship, there was six of us going on this inspection; the staff captain in full charge, the senior surgeon, the assistant surgeon, the purser, the chief steward and myself. It was to begin at half past ten outside the purser’s office on B deck. Then we would start to go all around the passengers’ rooms; we would inspect a room here and there, all the bath rooms, boilers and alleyways, and see that everything was clean and in order, and go right around each deck right down to the saloons and the galleys down to the steerage; the same thing in the crew’s quarters and the firemen’s quarters.”

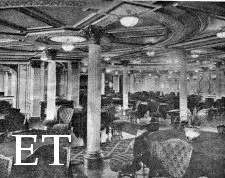

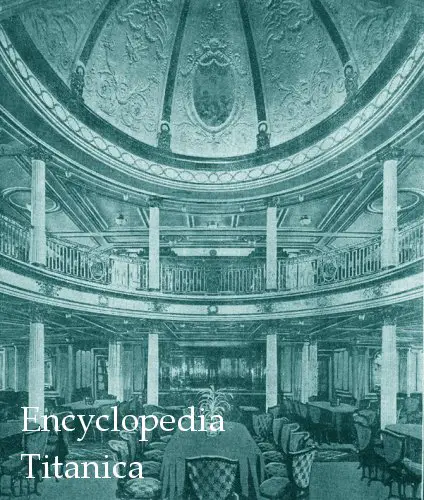

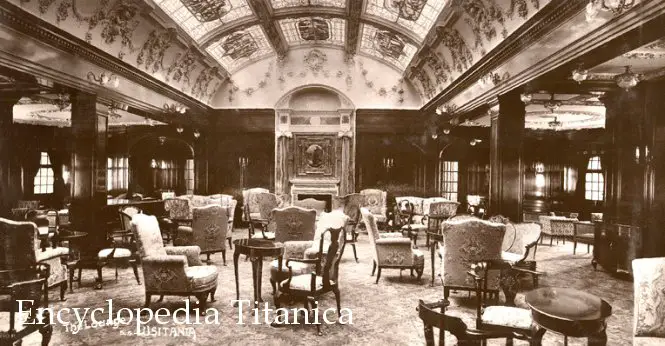

First Class Dining Saloon“We were all together and met on B deck. We all went together through the B deck section right fore and aft, and down to C deck, and the same thing through C deck, and then we all went down to D deck, and there we divided forces… The staff captain and the assistant surgeon and myself went through the forward end of the ship, through the sailors’ quarters and the third-class and steerage quarters and the stewards’ quarters forward and the store room, and we came along up C deck and went down through the third class entrance and followed the other route through the saloons and kitchens up into the second cabin and met outside the second cabin entrance of C deck, and we went along and went down into the firemen’s’ and trimmers’ quarters which had the entrance on C deck; we went down there. After we finished there, we used to pump back again and go up to A deck in through the verandah café and the smoking room and the house, and were dismissed when we got outside.”

First Class Lounge

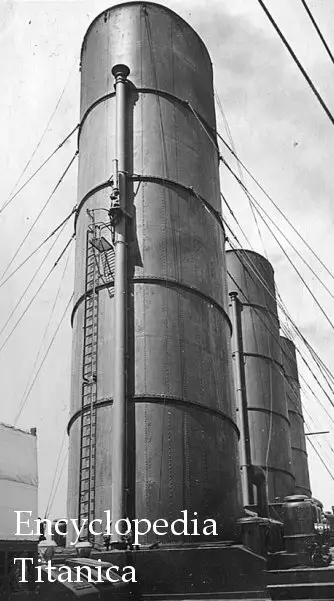

The appearance of the ship on the final voyage made a strong impression on John Idwal Lewis. When asked he would say, “A black hull, black funnels.” He was not the only one to describe the ship as having been re-painted from the traditional Cunard colors. Thomas Slidell described the funnels as “giant gray tubes.” Sarah Lund, in her charges against Cunard, claimed that the superstructure was painted gray. Lewis would disagree, while testifying on behalf of the company, and say that superstructure itself was still white.

Sailing day was especially busy and Lewis had to make sure several tasks were carried out.

“The morning we left Liverpool we had a Board of Trade mustering drill just before we sailed, under the supervision of the Board of Trade Supervisors; just to muster all hands and all the ship’s members and swing the boats out on both sides, and swing them inboard again.”

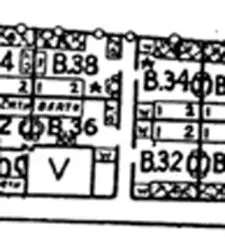

He was in charge of the starboard side during the drill, boats 1 to 11, which was next to the quayside, and his boats could not be put in the water. He was not sure if the boats in the port side were rowed in the river. Crewmembers were assigned a certain boat when they signed on, receiving, “a metal badge with the number of a boat on it.” Boat lists were also provided on the ship.

“The names of all the crew put outside their boats. The boat list is a paper and the diagrams for the boats on the port and starboard side with the names of the crew. If I remember rightly, there were three posted aboard the ship. They would be in the living quarters of the different staff for instance where the stewards have their quarters; they would be even down to the glory hole facing them and you cannot mistake them going downstairs.” They were also “in the firemen and sailors quarters… Each officer had a book with the name of the men in his section of the boat, corresponding to the sheets.”

Following the transfer of passengers and crew from the Cameronia, whose voyage was cancelled, the Lusitania was ready to sail. Lewis remembered years later that he looked out and saw a woman running along the dock.

“I saw the gang plank being raised and then lowered again… I happened to be the mail officer on the ship and just when coming on board, after checking the mail, a shout came from the shore, ‘Wait! Wait a minute! Wait a minute!’ And I happened to turn around and saw a lady coming up the gang plank.”

He said that he later learned that it was Alice Middleton.

As the voyage progressed, Lewis may have become familiar with the stories of the crew members with whom he came in contact. Staff Captain Jock Anderson had his nephew George Edward Latham aboard as an electrician. Second purser Percy Draper’s wife was expecting a child, which was due upon his return to England. Albert Bestic, the junior third officer, was to have joined the Leyland Line for his first ship assignment as an officer, but was transferred to the Lusitania. Second officer Percy Hefford, a graduate of the famous Rugby School, had recently gotten married three months earlier. Extra chief officer John Stevens had recently received word, while chief officer of the Cephalonia, that his wife had died. He had to complete another voyage on the ship and then he was allowed to return home- on the Lusitania. Stevens was lost on May 7th, as were Latham, Anderson and Hefford.

There were daily boat drills, but not for the passengers.

Q Had there been any boat drills during the voyage, prior to May 6th?

A Yes, an emergency drill… Well, we have two special boats in the ship that are always at sea swung out… I think they were 13 and 14; I am not absolutely certain; we used to have special wire guys spread out between the two davits with a life line attached to these reaching down to the water’s edge. Every morning, or usually every morning the whistle would go and these men went back to muster at the emergency boat. Whichever side of the ship was the lee side. There was a picked crew from the watch… Then after these fellows would stand at attention in front of the boats and I would say, “Man the boats,” and these men would get into the boats and put their life belts on and sit in the number of their place in the boat. After I saw that everything was all correct, I would dismiss them from the boats. This was done under my supervision, daily.Q Let us go back a moment, and tell us what the signal for the emergency drill was?

A The steamer’s siren; they used the blow the steam whistle… a long blast and a series of short blasts.Q What did the pursers and stewards have to do at this drill?

A The pursers look after the ship’s papers and the stewards attend to provisions, and so forth, and were attending to blankets and there were the stretcher guard, the ambulance guard.

The lifeboats were readied on the morning of May 6, as the ship approached the war zone.

Q When the boats hang in the davits with these short chains on them how high up are they above the deck?

A Well, they should be–the boat should be about 8 feet from the deck.Q Could anybody get into them at all?

A Well, I suppose I could if I jumped.Q And when the boats were swung out the morning of May 6th, you say they were lowered down to be on a level with the collapsible boats?

A Yes.Q How high would that bring them down above the deck?

A The collapsible boats would be about 3 feet–about five feet; you have to go over the collapsible boat to get into the lifeboat. The lifeboat was not lowered to the level of the deck, but to the collapsible boat; just a matter of 2 feet.Q Could the lifeboat be lowered after that was swing out, to be level with the collapsible boats, with out disengaging these chains to which they were hung in the rocker?

A Impossible.Q Won’t you describe the collapsible boats?

A A collapsible boat is something similar to a life raft, rather flat bottomed, it only raises about 18 inches from the deck… just like an ordinary (boat)–two bows on it and wider in the beam and flat bottoms. The wooden part of the boat is only about 18 inches deep… Decked over, watertight tanks, inside. Above that there is canvas sides that you raise up, like opening a concertina, fixed up with iron bars to raise the seats up.

He stated, “All the ports were to be closed and not only that, all the windows at night were to be closed and darkened and all the doors leading to the decks were to be closed at night.”

Lewis was careful with his wording while testifying, lest he be contradicted by other witnesses:

Q Were any ports open, so far as you know?

A No, not as far as I am aware of it, no.Q On the day of the accident?

A As far as I am aware of it, no.Q Of course, you were not in any passenger’s staterooms to notice the ports?

A No.Q But the ports in the alleyways and in the places you were in were in what condition?

A They were closed, all those ports; one or two of these might be open on C deck. They open on to the shelter deck; there were men detailed every morning to clean the brass work on those ports, because they open on to the third class passengers’ promenade deck and there are two men specially detailed off to clean the brass, and probably they were cleaning them at the time, and there might have been one or two open, but if any water came in there it would go down the wooden deck and would run out through the scuppers.Q Did you attend on the night inspection of May 6th?

A Yes, I didQ At what time?

A From about half-past eight until 10 o’clockQ What was the condition of the ports that night?

A They were closed as far as I could see; some places of course I couldn’t go.Q To what do you refer?

A I refer to some of the staterooms of the passengers.Q Had there been orders to have all ports darkened?

A Oh, yesQ Were you running without lights?

A We were.

Lewis had an unenviable shift the day of the sinking. “I was on from 4 to 8 in the morning… on the bridge… with the chief officer… I remember that when I went on watch in the morning that I had my overcoat on and was glad of it too. Yes it was foggy.”

He had a quick breakfast, and from there was off to the baggage room.

Q Where was the baggage room, by the way?

A It was down – the entrance is on C deck, it is right in the bottom of the ship.Q Were you down there continuously, or were you up and down?

A I was going up and down.Q Were you on deck at all?

A I was out on deck, on C deck.Q On the side, so you could see the condition of the weather?

A Oh, yes, you could see all around… It was, as far as I can recall it, foggy all morning.Q What was the conditions of things then, as far as being able to sight the land was concerned?

A Well, the weather was clear, but hazy over the land… I could see land all right, but I didn’t take too many particular notice what it was; I knew were we out to be, so I guessed where we were.

|

| Dining Room |

He finished his duties about quarter of one, and proceeded to his cabin to change for lunch. He was going to join first officer Arthur Rowland Jones in the first class dining room. His table was “on the port side… the after table of all on the portside… It was right from the side of the ship, right to the door of the grill room, to the entrance of the grill room, a square table.”

Q Did you notice anything about the ports in the dining room while you were having your lunch?

A No, they were shut on my side, as far as I could see.

Several passengers in the dining room contradicted Lewis.

James Brooks: On my left, I sat facing the bow and very near the entrance on the left of that section of the dining room that was all open. That would be just the same as these windows are here, and I sat on the port side of the center line at the dining table; they were open on that side.

Rita Jolivet: They were open.

Frederic Gauntlett: Nearly all were open… Well, I left my coffee and nuts and rose from the table and shouted to the stewards to close the ports.

Oscar Grab: I noticed that they were open.

Charles Lauriat: Yes, because there was an electric fan right over my head, and with the portholes open, the draft and the fans going at the same time made it very drafty.

Isaac Lehmann: It was a beautiful day and all the portholes were open.

The band was playing ‘Tipperary’ and Lewis was “just about finishing” his lunch when there was an explosion. “I should say it was just like a report of a heavy gun about two or three miles away from us.”

Q From what point on the ship did it appear to come?

A From the fore part of me on the starboard side.

Then he heard something else.

“A few seconds afterwards, whether it was an explosion or not I couldn’t say, but there was a heavy report and a rumbling noise like a clap of thunder… It was accompanied by the sound of broken glass, like glass breaking. That was on the starboard side again, forward of me, but closer than the first one was, further aft that the first one. I stood up and looked around and both of us walked out of the saloon. Of course, we couldn’t run out, there were too many people ahead of us.”

The ship began listing immediately.

“I should think it would be about 10 degrees when I was on the staircase. I went up along the main saloon staircase up to C deck. The only difficulty was that the place was crowded with people ahead of me. I came out on to the C deck on the port side and went up on the boat deck along the outside ladders, the outside staircases.”

One of the first people he saw was Mr. Piper, the chief officer, “standing by No. 2 boat.”

Q Had the ship begun to swing over toward the land yet?

A She must have, because when I went over on to my own station I could see the land.

Going to the bridge he found the quartermaster. “I sang out to the quartermaster and I said, ‘What is the list on the telltale, on the compass,’ and he told me 15 degrees.” He had no lifebelt. Percy Hefford, the second officer, had thrown him several from the bridge, but he gave them to other people.

He went to his own station, boats 1-11 and found Mr. Jones on the starboard side as well. One of the first things he noticed was that lifeboat 1 “was lowered into the water before I got up there, but the tackles were fast to it, the after fall was a bit tighter than the other one, so the boat was heading out to sea and had been drawn sideways along the ship, but it was floating in the water.” There were two sailors in it.

He did his best to fill the boats in his section, but almost none got away.

“Well, filled them up with passengers, with people; I don’t know whether they were passengers – I filled it up and lowered it down… The list of the ship would swing the boat out from the edge of the ship… When we had taken the women passengers on to the edge of the collapsible boat to get into it the distance was such that they rather drew back instead of getting in it; we had to use our best judgment to try and get them into the boat. Some were afraid of attempting to go across.”

Q How many people do you think were in?

A Well, it was loaded, as far as I could see, full; of course, I didn’t stop to count them; I ordered them to lower away and it was lowered away… I saw it unhooked and settle in the water.“When I was standing on the deck I saw a fishing schooner way over inside, and was looking at that and wishing it was a bit nearer, and I could swim for her, but I could see the land too and was wondering how I could make it.”

Not everyone was cooperative:

“When I was getting one boat out, I forget the number, I was standing on top of the collapsible boat seeing it lowered down and it was full up and these fellows when they saw the boat being lowered tried to rush it. Of course, I had to stop them.”

He made his way down the deck to work on the forward boats, and was opposite the first class entrance.

“I filled that boat; I saw that they started with the filling that boat, because when they were getting well under way there, I went further aft again and saw Mr. Jones and I said, ‘I had better give you a hand there, because they are filling mine up here,’ and that was one of the boats that he and I lowered. He took charge of one and I took charge of the other end, so that there people were lowered down properly.”

Following that, he claimed that he went back to his own section.

“I was continuously between no 1. and no 9. after that, going from one to the other, seeing that they were going all right.”

Q Did you get 9 down safely?

A It was lowered into the water safely.Q And unhooked?

A And unhooked.Q And away?

A Well, whether it drew away from the ship’s side, that was something I don’t know. I didn’t see it exactly going out, but I saw it in the water. I simply gave orders and said, “All right” and when the boat was in the water I said, “Get out with her.” A lady passenger was in the boat there, and I was standing on the deck and the boat was just away from the ship’s side and screwed up, and she stood up and sang out, “For God’s sake jump.” I looked at her and said, “Good-bye and Good luck. I will meet you in Queenstown.”

Working back and forth, the last boat he went to was 3. He said there were very few people left on the deck.

Q Were they able to stand up?

A No, not without hanging on to a bit of the hand rail on top of one of the houses; in fact, it took all I could to stand on the deck.

Looking about he saw, “the water was on the bridge deck and rising fast; I made an attempt to go aft and missed my footing, but I got hold of a collapsible boat… I was standing up to me knees in water, practically.”

To his surprise, he spotted a tiny gold watch, no bigger than the size of a quarter being swept along the deck by the water. He reached down and pocketed it.

“I fell in the water on the deck and got hold of the collapsible boat and scrambled on it and got hold of the rail on the funnel deck or hurricane deck, and got over there and tried to make my way across to the port side to take a dive off, but I was just about half way across when she went down under me.”

Q When the ship went down were you drawn under?

A I must have been, because I didn’t see anything of the ship and I was in the fore end of her; when I came up to the surface there was no sign of the ship at all.

When he rose to the surfaced, he grasped a piece of a boat chock. “Sometimes I was on top and sometimes I was underneath it, and eventually I got alongside of a collapsible boat that was just floating stem up, about one-third of the boat sticking out of the water, and I got on top of that and was there half an hour when a trawler picked me up.”

He landed in Queenstown, and left the next afternoon for England. He rose, during the war, to the position of chief officer; one of his ships being the Carpathia. He gave several sets of testimony during the Liability hearings.

The fact that so few of the boats got away did not escape the lawyers.

Q I notice in the book that Mr. Lauriat wrote, I believe it was written while he was there in Great Britain after the disaster, he says (page 49): He speaks of seeing in the slip six lifeboats, inside the wharf at Queenstown. He mentions the numbers 1, 11, 13, 15, 19, and 21; did you notice at any time notice the numbers of the boats after you got to Queenstown, the ones that were brought in?

A I never saw them in Queenstown.Q Do you, yourself, know how many lifeboats you actually got away from the ship with passengers?

A No.

John Idwal Lewis attained the rank of Captain, and then was made the assistant marine superintendent of the Cunard White Star Line. He married a woman named Sophia and had two children, Henry and Joan. He made his home in New York and also vacationed in Inverness, Florida. He was a member of the Pyramic Lodge, number 490, of New York City. When he came across a newspaper interview fellow officer Albert Bestic conducted with Captain Turner, he was miffed that Bestic assumed he was dead.

Bestic wrote, “I am the only surviving deck officer of the Lusitania and with the anniversary of the great liner’s loss arriving, it occurred to me to go to Liverpool to see my old commander and find out how he was faring.”

Captain Turner was described as “alert” and made several interesting statements. Bestic asked Turner if he thought the ship would be torpedoed.

“Yes, I was distinctly worried. I was advised by the Admiralty that I was to keep a mid-channel course. As you remember, we were warned by wireless that there were six submarines waiting for us in mid-channel. That was the chief reason I closed in on the coast. I thought that if the ship were sunk near shore, the top deck might be above water, allowing the passengers to escape… I am certain she was struck twice.”

The former officer, turned writer, then asked about the rumor of gold aboard. Turner replied, “No gold of course, but there must be a lot of money and jewelry in the purser’s safes. I am quite sure of that.”

He chuckled about his own property left aboard the ship. “There are 15 (British pounds) that belong to me. That is all. But there is an old sextant I value. It’s in the left hand drawer of my desk on that ship.”

Lewis’s rebuttal came a few days later.

“I was third officer of that ship and standing by my station amidships, when she heeled to starboard and went down bow first. We managed to launch 6 lifeboats in which 700 person were saved… Three deck officers were saved besides Captain Turner. A.R. Jones, the first officer who was drowned later in the war, and Bestic, a young Irishman from Dublin, who was making his first trip in the Cunard Line- I think it was his last, because I never heard of him afterward. He was the junior third officer.”

On the 20th anniversary of the disaster, he had a reunion with several crewmembers who survived the sinking. It was held in his office at the New York Cunard White Star building. He met with, Richard Wylie, assistant marine engineer of the line, and William Ewart Gladstone Jones, chief electrical engineer of the Scythia. Later they were joined by Alexander Duncan, who was the chief officer of the Berengaria, and Charles Dunn, chief engineer of the Bantria. They planned on drinking a silent toast to all their shipmates who went down with the Lusitania.

He retired in 1950 and moved to California in 1956, as both of his children lived there. He settled in Stockton in 1960. The “short, taciturn” sailor spent his time sketching ships and working in his garden. Towards the end of his life, he suffered from illness and in his last year, resided at the Lodi Convalescent Home. Lewis, the last surviving officer, from the Lusitania’s final voyage, died on October 21, 1974.

|

| Alfred Russell Clarke |

|

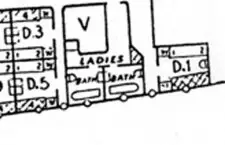

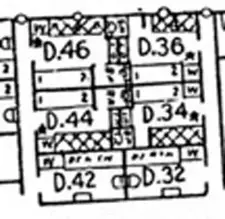

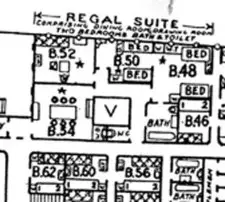

| Clarke’s Cabin (Paul Latimer) |

“This looks like a fine boat and I cannot help feeling proud that the British flag rules the British waves, and I have no fear of the German submarines. There is quite a crowd on this boat and apparently they are not afraid.”

Alfred Russell Clarke, a first class passenger, penned this note to his son Griffith before the Lusitania sailed. He did not have time to be afraid of submarines; he was busy with plans to expand his business by securing leather contracts with British Army. Clarke was an ambitious man. Born in Peterborough, he moved to Toronto at age 18 and founded A.R. Clarke & Company, Limited, which eventually became the foremost producer of patent leather in the British Empire. His factory employed over 350 people who produced leather linings, leather vests, moccasins, and other articles of clothing in which leather was used. He was married to Mary Louisa, and had a son, Griffith, and a daughter, Vivien. He belonged to many organizations including the Riverdale Business Men’s Association; Toronto Housing Co.; Toronto Civic Guild; Canadian Manufacturers’ Association, Ontario Motor League; and Masonic Order. He was also the treasurer of the Metropolitan Methodist Church.

On May 7, Clarke was comfortably settled in a chair on the top deck when, “there came the sound of a loud explosion. Fragments and splinters flew all around and a great torrent of water was forced up by the explosion and poured over the deck. The ship instantly took a severe list… The stairway was already crowded with people trying to get life preservers… I started to go to my cabin, but found it difficult owing to the angle and I returned to the upper deck.”

He stood at the back of the crowd, adhering to the rule ‘women and children first’, and did not push his way forward. Talking with others, he heard that the Captain had ordered that boats not be lowered.

“As the list grew greater, I again tried to reach my cabin for a lifebelt. The cabin was utterly dark. I felt to remain there I would be caught like a rat in a trap. The cabin door closed as I entered… I was distressed to find the door jammed… I could not open it owing to the acute angle of the ship, but got out through a side door, and mounted the deck again.”

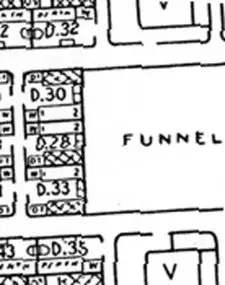

Author’s Note – He had a small inside cabin, D-3, which on the original deck plan for the Lusitania appears not to have a connecting door. However, one may have been added later, or more likely he may have upgraded while onboard to a cabin that did.

He encountered a young man who had sat his table in the dining room. He was tying on a lifejacket and asked Clarke if he wanted one.

I took it and as it was impossible to stand upright, I suggested to my companion that we should take no more chances, (and) to try for a boat… He said: ‘Oh no,’ and that was the last I saw of him…Glancing over I saw two boats being lowered jambed (sic) together and trying to get free. The other boat was trying to shove off from us. The four great funnels were now hanging at such an angle as though they would soon touch the sea. Then I was torn down in the whirlpool. I seemed to touch the very bottom of the ocean.”

Clarke felt something gripping his chest, “crushing me. Something else seemed to wrench me around. I was twisted and racked. All this time I was fully conscious. I remember hoping this would soon come to an end. Suddenly, what was holding me let go, and I rose rapidly to the surface.”

The next thing he recalled was floating near a boat and two sailors pulling him aboard. The only person he recognized was fellow Canadian, Leonard McMurray.

The sea was full of people. There were perhaps five or six boats around. Bodies floated by us. The corpse of a baby clung to the bottom of our boat. We could not reach it. A woman floated by, foam coming from her mouth. I put out my hand, but as I touched her hair, she passed away.”

They drifted about for three hours until they were rescued. He did not remain in Queenstown long before making the trip to London. Once settled in the Hotel Cecil he called for doctors to attend to his injuries. It was discovered that he had a broken rib and was taken to the Fitzroy House Hospital. His temperature rose to 102 and the doctors found that the broken rib had affected a lung and pleurisy had developed. His wife was sent for at once, and Mary Louisa sailed for England and arrived in London on June 12. Meanwhile, pneumonia had also set in. At first, Mrs. Clarke had high hopes for her husband and sent telegrams home saying that his improvement was “more than maintained” and that great hopes were entertained for his recovery. Griffith Clarke had intended to also come, but his mother told him it was not necessary. But then Alfred took a turn for the worse. His family received two telegrams.

“Your father very weak. Mother very discouraged. Time very short. Advise you not to come.”

Shortly thereafter, another telegram arrived.

“Mr. Clarke is sinking rapidly. We are with your mother and will give her every attention.”

Alfred Russell Clarke died on June 20. A family friend cabled Griffith and Vivien

“Your father passed peacefully at 9:20 tonight. We will take care of your mother and arrange everything for her, including her passage and your father’s home. Cable me any instructions.”

Mrs. Clarke came home on the Lapland and proceeded to Toronto with the body of her husband. Following the funeral it was determined that he left an estate of $521,825.28, part of which was comprised of $34,845 in life insurance and $50,000 in accident. His real estate holdings were valued at $41,140 and the fair market value of the stock in A.R. Clarke and Company, Limited was shown to be $393.000. Griffith Clarke was appointed managing director of the company and following his death in 1923, it was alleged by his mother, in her case against Germany, that he ran the company into the ground and that had his father survived, the business would have prospered. How true this is, cannot be said. What is known is that Mrs. Clarke herself had an active interest in the company and when her son died, she took full charge. Mary Louisa filed a claim against the German government that totaled $125,000. At the time of the claim hearing in 1925, she was drawing a salary of $24,000 a year from the company. Commissioner James Friel was not sympathetic to the various claims and awarded the widow $7,500, which he deemed ‘fair compensation.’ He stated that

“the insurance money alone at her age would have purchased for her an annuity of over $6000 a year. I do not think it can be said she suffered any pecuniary loss resulting from the death of her husband.”

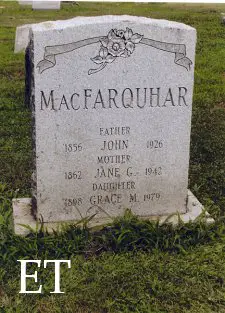

Mrs. Jane MacFarquhar, a woman of about 53 years in 1915, was traveling to Scotland to settle some family financial matters when she survived the Lusitania disaster. Some years previously, Jane had inherited her father’s estate in Burghead. Mr. Grant’s will allowed his wife, Jane’s stepmother, the right to use the estate he had left to Jane while she, Mrs. Grant, lived. Mrs. MacFarquhar had learned that the 83 year old woman was seriously- and likely terminally- ill, and, in seeming anticipation of her death, was traveling to the paternal home to oversee the eventual disposal of the property. Her youngest daughter, Grace, 16, accompanied her. The MacFarquhars booked second class passage on April 27th 1915, and planned for a long stay, of undetermined time, in Europe.

Like so many other survivors, Jane later described the voyage as being an extremely pleasant one. And, like so many other passengers, Jane would relate that there was a sense of unease as the ship entered the war zone:

Jane and Grace spent their final mid-day aboard the Lusitania preparing for disembarkation the following morning. They carefully laid out changes of clothing for themselves, before attending luncheon in the Second Class Dining Saloon.

The MacFarquhar’s boat was eventually picked up by a British patrol boat, and they were landed at Queenstown around 9PM. Jane and Grace remained in Scotland for more than three years before returning to Mr. MacFarquhar, and their home in Stratford Connecticut, at the war’s end. Life was at first comfortable for the family. Grace studied nursing in New York, and graduated as a registered nurse from Metropolitan Hospital in 1924. A biographical sketch of the MacFarquhars published in the 1930s claimed that an unnamed “nervous condition” Grace and her mother blamed on the Lusitania experience deferred her nursing career. After John MacFarquhar’s death in an explosion at Christmas 1926, Jane and Grace’s fortunes allegedly declined precipitously. By the mid 1930s they were living in a small but comfortable duplex at 199-201 Hollister Street in Stratford. One of Grace’s arms was partially paralyzed and Jane, in her 70s, was supporting the two of them by tilling her small vegetable garden at the home she “owned clear.” They were the subject of a newspaper profile on the anniversary of the disaster, which may have exaggerated their penury for ‘human interest’ but which contains their last known – and bitter – public statements about the disaster. Jane died, at age 79, on April 21, 1942 and was buried beside Mr. MacFarquhar at Stratford’s Union Cemetery. After Jane’s death, Grace may have returned to nursing. Details are sketchy, but a letter written by her brother, Colin, in the early 1970s reveals that by then she was under the care of her niece, Mrs. Jane Peck, of Bristol Connecticut. She died in New Britain, Connecticut on February 9, 1979, at age 80, and was returned to Stratford for burial beside her parents. The MacFarquhars share a single stone and are the easiest grave in the cemetery to locate- they are literally the first grave on the left as one passes through the entrance. |

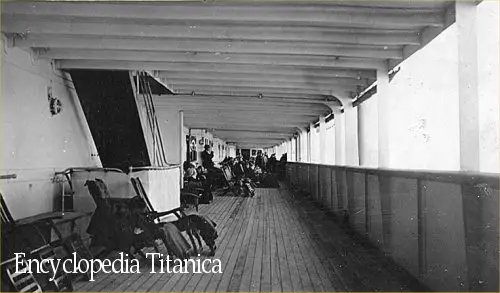

Well Deck

Mrs. James Logan was returning, along with her two and a half year old son, Robert, to Ayr, Scotland, for the duration of the war. Her husband had enlisted early on, had been wounded in Ypres in November 1914, and by May 1915 was once again at the front. Mrs. Logan was leaving their residence of one year in Paterson, New Jersey, for the security of her girlhood home. Mother and son traveled in third class, and Ruth Logan survived the disaster. Her account remains among the best of the few left by third class passengers: it begins on a staircase where, at the moment of the torpedoing, the young mother was making her way to the open deck with her child walking ahead of her so that if he missed a step he would not fall far.

I never let him out of my sight, as I was afraid something might happen to him. There were people coming behind me, and when the shock came we were all jolted about. I immediately seized Robert and ran on deck. The vessel had a considerable list to one side, but she righted herself for a few minutes and several men clapped their hands and tried to reassure us that she would keep afloat.

The day before the disaster there were sports on board and as Robert was too wee to take part in the general amusement, I took to running after him crying as I did so “I’ll catch you!” And, oh! The tragedy of it all. When the rush for lifebelts came Robert could not understand it all and lisped the words I had used the day before.

Everybody seemed to be running around, and everybody seemed to be getting lifebelts. I appealed to several, but no one in the excitement heeded me until a sailor came along. I took him to be an officer. “Wait a second and I’ll get you one” he said, and he immediately reappeared with a life jacket and he put it around me. I said to him “What about the child?” and he replied “Put him in along with you” and he lifted my child and put him inside the jacket which was around me.

He immediately began to struggle, and wanted down on the deck, and another sailor passing me a minute later advised me to put him down till he could get the jacket put on right. I asked him to get a lifebelt for the wee chap, and he hurried forward to get one, and at that moment the ship went over. I held onto his hood and we went down together, and I still had a grip of him when we came to the surface, but the child’s struggles and the struggling of hundreds of others in the water around me caused us to be separated.

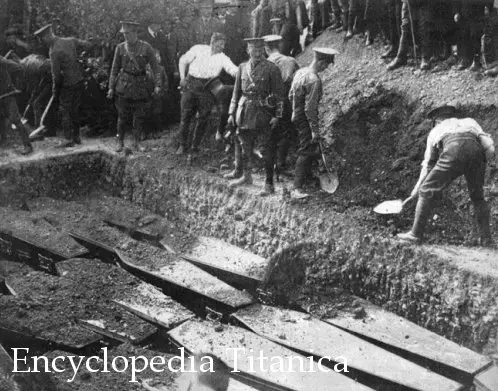

Mrs. Logan was in the water for nearly five hours before she was picked up, unconscious, by a torpedo boat, around 7PM, and was still unconscious when she was brought ashore later that night. She awakened in Haulbowline, where, at first, she assumed that her memories of the tragedy were of a horrible dream. Before traveling on to Scotland, she was able to identify her son’s body in Queenstown. Robert Logan, body #42, was buried in common grave C in Old Church Cemetery.

Common Graves

Mrs. Logan’s husband, Corporal James Logan of the Gordon Highlanders, survived the war, and they returned to New Jersey together. Several more children were born to them, including a second son named Robert but their life together was not to be a long one: the 1930 census lists James Logan as being a widower.

|

| Terence Florence Gray and her son, Stuart (Paul Latimer) |

Terence Florence Gray, of California, boarded the Lusitania with her son Stuart, 3, and father- in- law James Paul Gray. His wife, Carrie, was abroad, visiting the ancestral home in Scotland, and the three were to join her for an extended vacation.

James Paul Gray survived, injured, by clinging to an overturned lifeboat, but his daughter in law and grandson were lost without a trace. He was later to learn the details of their final moments aboard the ship, which perhaps gave some small comfort to him, his wife, and his son William Hiram who was Terence’s widower: Mrs. Gray and her child at least had gotten clear of the Lusitania and were not trapped below decks when it foundered.

Terence, known informally as Florence, had just put Stuart to sleep in a deck chair when the torpedo struck. She was together for much of the duration of the sinking with her shipboard friend, Maud Turpin. Presumably they searched for their missing relatives as long as time permitted, but what is known for certain is that at the end the two women stood with Stuart Gray and Thomas Turpin on one of the upper decks and stepped into the sea together as it washed towards them. Only and Mr. and Mrs. Turpin survived; she was reunited with her husband in Queenstown and later gave an account to the Gray family. Mr. Turpin later gave an account in which he said found his wife aboard the Lusitania, before she sank. He did not mention seeing Florence or Stuart Gray being with his wife, but did say that after the ship foundered, he was able to climb atop the same capsized lifeboat as Mr. Gray.

This indicates that at the end, Florence and her son were very close to their missing relative.

James Paul Gray never fully recovered from the injuries he sustained in the sinking, dying in September 1922. His widow was awarded a settlement of $10,000.00 by the Mixed Claims Commission. William Hiram Gray received $25,000.00 for the loss of his wife and son in January 1925.

|

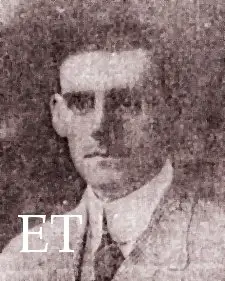

| Edward Harris Lander (Michael Poirier) |

|

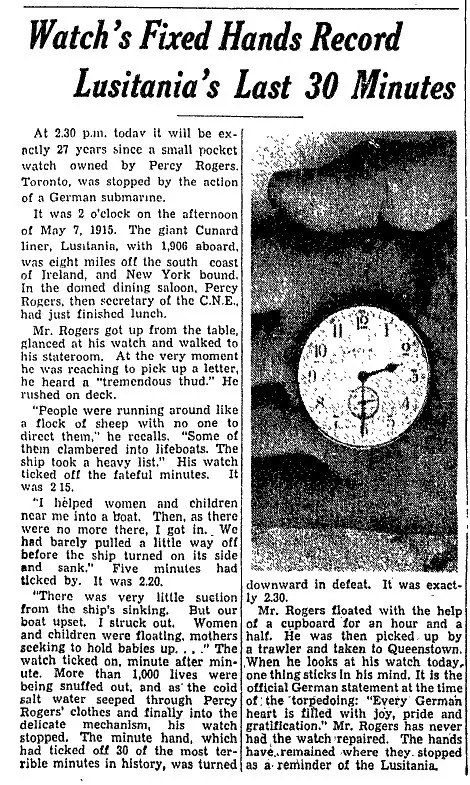

| Cunard Daily Bulletin May 6 1915 |

A happier ending lay in store for Mrs. Sarah Fish, who was part of an extended family party traveling aboard the Lusitania. All but one surmounted the odds by sinking with the ship and surviving. The lost child-her youngest- spent the last minutes of her life with a heroic man who did his best to save her.

Edward Harris Lander was born on November 23, 1882 in Glen Ochil, Scotland to an Irish father and an English mother. The family settled in Bristol, England in 1901, from where Robert emigrated to the Untied States ca 1907. He met and married a woman named Christine in Chicago; they had one son, Robert. They lived in New York where he worked as the U.S. representative of a London firm. His trip on the Lusitania’s final voyage combined business and pleasure for he planned to visit his family in Bishopston, Bristol.

On the voyage he made the acquaintance of Elizabeth Rogers and her sister Sarah Fish. Mrs. Fish was bringing her three daughters back to England for the duration of the war while her husband Joseph served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. They were, in descending order: Eileen, age 10, Marion, age 8, and Joan, about 6 months. Mrs. Fish recalled that there was much banter regarding the German warnings, for no one she met took them seriously.

On the day of the sinking, Edward Lander and Elizabeth Rogers finished their lunch and went for a walk on deck with baby Joan. Meanwhile, Sarah Fish continued to dine with her middle child Marion while Eileen played on deck Lander was standing by the rail with his friend when someone turned his attention to the wake of the torpedo.

“The missile headed straight for the Lusitania, and hit her about mid ship. Someone cried out, ‘It’s got us,’ and upon contact with the vessel, the torpedo exploded with a dull sound, not making a big racket. We saw a big cloud of smoke; the engines of the Lusitania stopped, and the vessel took a list to starboard.

Authors note: Although Lander said the ship listed to starboard, he claimed that he saw a torpedo strike from the port side.

We crawled onto the first cabin deck and with many others with us, and soon there was lot of water on part of the deck. I gripped the baby and held the young lady by the wrist, and we managed to scramble to the deck where the boats were. That deck seemed pretty clear. The lady and I found a lifeboat, into which we got, and I kept the baby in my arms. The boat was crowded with members of the crew, so there was not much room to turn round in her. Then somebody came alongside and said, ‘It is all right. She’s on the bottom.’ Thinking it safe to return to the ship, we all got off our boat and again went aboard the Lusitania. Doubt arose to the safety of the ship and people began to get into the boat again. Suddenly, the Lusitaniasank. Our boat was attached to her by a rope, and we went down with the steamship. The baby was wrenched out of my arms and it seemed, in going down into the sea, as if I turned over and over again. Then I felt myself coming up again. I came to the surface, but sank once more. Coming up a second time, I struck out a little and saw an over turned lifeboat a little way off. One man was on it. I reached hr, and getting on her, lay for a little while. I was very nearly unconscious. When I recovered somewhat we saw a woman’s dress in the sea- merely the back of the garment was showing. The man in the boat got hold of the woman’s head and I held on to her clothes, and we pulled her on to the flat bottom of the overturned lifeboat with us.”

“Soon after, we saw a collapsible lifeboat, with six men on her – members of the crew, I believe. Her side was stove in, but she kept afloat. We hailed her; she came to us and they took us aboard. I was shivering greatly, and one fellow who seemed in command, told us to take an oar. The pulling worked up a little circulation and made one feel better. Then, someone else took a turn at pulling and I was put back on the bottom of the upturned lifeboat again. There were many people floating around, and we saw two men and a woman hanging on to a tank boat. Those were afterwards rescued by the collapsible boat. The lifeboat on which I was allowed to drift for a time and for a time was secured to the collapsible by a rope. Boats dotted the sea, and hope was raised by a little fishing smack that could be seen off the Irish coast. There was not much wind, however, and the smack went towards the coast instead of coming to us. Possibly she had as many people aboard as she could take. There were lots of deck chairs floating around, but we saw only one that as being used as means of support and that by a woman who also had a lifebelt. Then we arranged to cry ‘Help’ in chorus. H.M.S. Bluebell, a government tug or patrol boat, came to our assistance…”

The Fish family had a horrific experience as the Lusitania went down. After the first explosion, Eileen made at once for the second-class companionway and went down stairs. Despite the confusion, she met her mother and sister and the three made their way back on deck. A stranger came along and handed Sarah a lifebelt which she gave to Eileen. She would not take the lifebelt from her mother, so the stranger gave Sarah his own belt, allowing each woman to have one. The three stood waiting until the ship foundered, and were dragged under as she did. Sarah held onto Marion until they reached the surface. She could not see Eileen. In the distance, she spotted a boat, but when it approached the occupants claimed that they were full and could not take Mrs. Fish or her daughter in. An oar floated by and she placed it under Marion’s arms. A little while later, the occupants of the same boat relented and took the mother and daughter aboard. At first, Marion appeared to be dead and the people in the boat said she must be put overboard. However Sarah was proficient in artificial respiration and worked for over an hour until Marion came around. When they were transferred to a collapsible, she found Eileen. Following the sinking of the Lusitania, Eileen swam to the collapsible where she latched on to a lady’s cape that was partly hanging over the side and held on until she was pulled aboard. Elizabeth Rogers remembered little of her time in the water. She said she went down and down, and to her surprise came back up despite the heavy coat she was wearing.

Sarah Fish was very grateful to Edward Lander for attempt to save Joan, but he never forgot her death. He booked passage on the Saxonia and returned to his wife and child. The ship arrived on June 29, 1915. The only other passenger aboard with a connection to the shipwreck was the aged father of Hugh McFadyen. Landers’ experiences on the Lusitania did not deter him from traveling and he continued to sail.

The Lander family eventually settled in Wa Keeney, Kansas. Edward referred to the Lusitania infrequently and never at length. He did keep one memento- the May 6, 1915 Cunard Daily Bulletin which was in his pocket when he went overboard. Edward Lander passed away on January 31, 1973 at age 90.

John Moore was born in Belfast, Ireland and was one of six children. He and his siblings grew up on a farm in Ballylesson above the river Lagan. As he grew older, he worked as a grocery store clerk and was well known in the area as a football player. When he was 19, he decided to emigrate to America. He booked passage on the Lusitania and arranged to stay first with a friend, Mr. Gordon before settling in Manchester, Connecticut. His sister Jeanette, also known as Nettie, moved shortly thereafter to Newark, New Jersey with her new husband Walter Mitchell. In 1915, when John found out that his sister, brother-in-law, and nephew were going home to Ireland, he decided to join them for a visit. They booked second-class passage on the Lusitania. He and his family sat together during meal times and to while away the voyage, he and some shipboard friends played cards. On the day of the disaster, he finished lunch and went to continue the card game. When the ship was struck, he put the score sheet in his pocket and hurried on deck. He said that he felt early on that the ship was doomed, and that the passengers he encountered were hysterical. He watched a boat being lowered when the line jammed in the block. The boat overturned and sent its occupants into the water. Looking about, he saw a partially filled boat and jumped in. He heard a “sickening snap” and the line in the block parted. The boat swung crazily from the forward davit as the aft part of the boat dropped down. John clutched at the gunwale as the people and equipment from the boat fell into the sea. As he had hung from the rope, people jumping from the deck hit him, but he managed to hold on. He moved hand over hand up the rope until he gained the boat deck of the Lusitania. A lifebelt was lying on deck and he put it on. The ship suddenly dived and he found himself in the water. John was swimming “blindly” when he came across a young boy crying, “Save me!” He placed the child’s two arms around his neck and swam towards an overturned boat. They clung to the craft as people dropped off. None of Moore’s accounts name the boy or say if he survived. Eventually, he was taken aboard the Indian Empire. In some accounts he claimed to have met his sister aboard the rescue ship while in others he said that he found her unconscious in Queenstown. His brother-in-law and nephew perished in the disaster: a photo of the body of Walter Dawson Mitchell, Junior, appears in Lest We Forget part 1. Moore remained with his family for a few months before booking passage back to Connecticut on the Carpathia. Also aboard was survivor Joseph Thompson. They were off the Irish coast, Sunday, July 18, when a periscope was sighted. The British patrol fired at the submarine. Joseph Thompson said that the Carpathia continued on a zig-zag course until after dark. John had very specific memories of his voyage home.

Captain Prothero of the Carpathia stated that he thought the patrol were at target practice, not firing at a submarine. Following his return, John worked as a meter tester and married in 1924. He owned his own home and felt he was doing well in life. He saved the Cunard Daily Bulletin, dated May 6, 1915 and over the years showed it to anyone who was interested. The headline- “British Success in the Dardanelles.” He passed away on May 27, 1946 at age 54. |

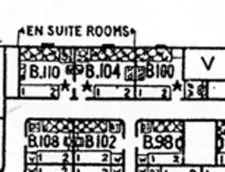

Anne Shymer, 36, of New York City, was the president of the United States Chemical Company. She was aboard the Lusitania en route to London where she was to be presented to King George and Queen Mary at the court of St. James. Mrs. Shymer was born in Logan’s Port, Indiana on 30 May 1879. Her mother, Grace, made sure that Anne and her younger sister Maibelle were well educated and encouraged Anne’s interest in chemistry. Anne studied at Cornell University, and she likely transferred to, and graduated from, another institution for Cornell does not have her recorded as a graduate.. She was married to a nobleman named Paterson for a short time and lived abroad until he died. Anne returned to the United States and continued her experiments in a private laboratory in New York. She remarried on 16 January 1911 to Robert Shimer. They lived together as man and wife for a period of four weeks and then separated. He took off for parts unknown, and she anglicized her last name to Shymer. Anne was successful as a chemist and formed the United States Chemical Company. She discovered a formula for bleaching textiles and for a germicide be used in hospitals. In early 1915, Anne presented her discoveries to King George’s physician. She also dined with Premier Asquith and his wife. Anne returned to New York to make final preparations to expand her company’s business in London. The chemist joked with friends and family that she was to be presented to the King and Queen, “Scientifically if not, socially.” Anne had returned to the United States aboard the Lusitania, and chose to sail back aboard her as well, because it had been such a pleasant crossing. She carried her formulas with her. Her family came down to the pier to see her off, and photographed her aboard the Lusitania, standing on the B-deck promenade near her cabin B-98. The one thing she had not been able to do before sailing was locate her husband to commence their divorce proceedings. Her actions aboard the Lusitania are unknown; however, when the ship was struck, she may have been calmed by assurances that the ship would not immediately sink, which survivors later recalled hearing. She may have gone to her cabin to retrieve her jewelry. Her body was among the first recovered and was numbered 66. The jewelry found on her remains was estimated to be worth $3,900. It was handed over to a Mr. Thompson Vice-Consul, American Consulate, Queenstown, but was lost in transit between Cork and the American Embassy in London. Shymer’s remains were sent home on the steamer Philadelphia. Grace Justice-Hankins and her daughter Maibelle Heikes Justice filed claims for lost property and for the formulas that Anne was bringing to London with her. Robert Shimer learned of his wife’s death and filed a claim for $50,000. Grace Justice-Hankins passed away in 1924, before a judgment was made. Commissioner Edwin Parker immediately dismissed Robert Shimer’s case as he and Anne had not lived together as husband and wife since 1911. Parker noted that since the chemist had not filed for a patent for her inventions, he could not award her estate any money for them. He rendered his decision on October 30, 1925 and granted her estate, which had previously been awarded $3,900 for the missing jewelry, an additional $7,525.00. Her mother’s estate received $7,500 as did her sister Maibelle. |

A second inventor traveled aboard the Lusitania, but his intent was considerably less benign than that of Anne Shymer: Henry ‘Harry’ Pollard was returning to England with a formula for poisonous gas to offer to the British government. He was born in Bradford, the son of Edwin Pollard and was one of several children. The family moved to Old Corn Mill, Silsden where spent most of his childhood. He chose, during the course of his education, to become an engineer’s draughtsman. He was also an inventor and was said to have obtained several patents. One of his later discoveries involved the use of liquid ammonia in the manufacture of ice. In 1914, Pollard left his home in Manchester to work on projects in the United States. He traveled aboard the Transylvania, which arrived in New York on December 16, 1914. His destination was the Victor Building, Washington D.C. where he was to stay with an acquaintance named Middleton. He was engaged in installing machinery for an ice plant when an explosion occurred. It left several men unconscious and another near death. The cause of the explosion intrigued Pollard and while investigating its origins, he believed that he found something that could help offset the effects of the gas bombs used by the Germans. He spent much time refining his discovery and when he was done, he believed that it would prove to be far more destructive than anything invented by the Germans. He booked first class passage on the Lusitania, determined to offer his formula to the British government. His plans to help in the war effort were not to be, for he was lost in the shipwreck. His brothers Frank and Lewis traveled to Ireland, but despite their relentless search, they found no sign of Harry. The exact nature Pollard’s discovery has not been preserved – apparently, his notes were lost with him. However, his work immediately before the disaster investigating the explosive potential of refrigerant ammonia suggests was his gas weapon may have consisted of. Although one regrets the loss of Mr. Pollard, it is – perhaps – for the best that his discovery was never utilized. |

|

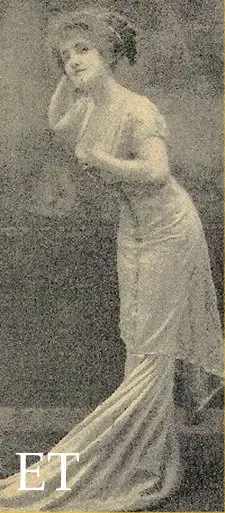

| Rita circa 1910. |

|

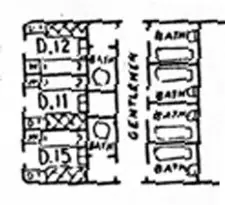

| Jolivet Cabin (D-15) (Courtesy of Paul Latimer) |

Rita Jolivet, stage and screen actress, remains one of the most frequently referred to of the Lusitania passengers. Unlike many others survivors, she apparently assimilated the memory the disaster quite well: although she spoke frequently of the sinking, she did not seem haunted by it, and the nightmares, panic attacks, guilt and anger which plagued the later years of so many of the Lusitania’s people do not seem to have been a major factor in her life. Her fame as a survivor has outlasted the acclaim of her dramatic career, and her 1917 testimony remains the best, and least fanciful, account of her experiences on May 7 1915.

Q When did you make up your mind to sail; when did you go on the ship?

A At 8 o’clock in the morning I made up my mind to sail, and I arrived at the dock at five minutes to ten. She was due to sail at 10 o’clock. The reason for my doing so was because the Lusitania was supposed to go quickly, and I wanted to see my brother before he left for the front.Q Had you expected, or thought of going on the St. Paul that same day?

A Miss Ellen Terry had suggested my going, and I said no, that I was in a hurry and was on schedule time and was afraid of not seeing my brother.Q When did the steamer finally sail, as far as you recollect?

A She finally sailed about 1 o’clock.Q Your stateroom was on what deck?

A On Deck D; it was a very bad room, because it was the last moment, and I had to take an inside cabin.Q Were you alone?

A Yes, but to my great surprise I found my brother in law was going back too. I met him on the boat. He had also decided to hurry back to his wife, and she was in England.Q There was no special circumstance on the voyage up to the day of the torpedoing?

A Not at all, except for rumors.Q On that day, on the 7th of May, Friday, did you notice anything about the speed of the vessel, as compared with her former speed?

A Yes, I noticed that she had slowed down.Q On Friday do you recollect seeing the shore at all, and if so, about what time?

A I saw the shore when I was in the water.Q Did you see it while you were on the steamer at all?

A No sir, because I had not slept well the night before and I had just got up for luncheon, and as I had an inside cabin I could not see the shore from my cabin.Q Where were you at the time the torpedo struck the ship?

A I was down in my cabin on deck D.Q Did you feel one shock or two shocks?

A I felt a great shock, and I was thrown about a great deal, and she listed tremendously.Q How soon did she begin to list after the shock?

A It seemed almost immediately; I didn’t think we were torpedoed, I thought we had struck a loose mine.Q What did you do after you felt the shock?

A I looked out and saw a woman putting on a lifebelt, so with great difficulty I climbed up and got hold of my lifebelt which I carried in my hand.Q Where did you get it?

A From the top of the wardrobe; I climbed up on my bunk and got hold of the lifebelt. I believe there was a second one there, but I couldn’t reach it very well. Then I climbed up on deck; I wanted to meet my brother in law who was waiting for me on deck A.Q You have spoken of the list that came immediately. Was that before or after you left your cabin?

A Before I left my cabin; with great difficulty I walked through the corridor and walked up the four flights of stairs to deck A.Q You found whom there?

A I found my brother- in- law and Mr. Charles Frohman, and a Mr. Scott. I believe there was another gentleman behind, that they said was Mr. Vanderbilt, but I don’t know; I am not sure of that.Q Did you put on your lifebelt then?

A No; my brother-in-law said “Did you bring any others?” and I said “No,” because I couldn’t reach the other. In fact, I didn’t know that there were other lifebelts in my room; there were, but I didn’t know at the time, in the hurry I just grabbed the first one. Then Mr. Scott went downstairs to deck B and he got up four lifebelts, and gave one to my brother-in-law, and one to Mr. Frohman, and one he kept for himself. And while he was helping Mr. Frohman on with his, and my brother-in-law was helping me with mine, someone stole his (Scott’s) lifebelt, and Mr. Scott went down a second time and brought up other lifebelts from deck B, and he gave his away to an old woman. We all offered him ours, and he said no, he could swim better than any of us, and if we had to die we had to die; why worry?Q Did you see any of the lifeboats lowered while you were up on deck A?

A Yes. We agreed to stick together and I looked out on the deck and I saw a lifeboat being lowered, but the guard slipped; it was not lowered evenly, and the women and children were thrown out.Q Do you remember which side of the ship that lifeboat was on?

A I am not quite positive; I am not quite positive but I think it was on the side that was nearer the port, nearer the shore.Q That would be the port side?

A Yes, that would be the port side.Q Did you notice anything about the list of the vessel as you stood up on deck A, whether it listed the same or whether it increased or not?

A No, it did not remain the same. She righted herself. She seemed to right herself. It was only noticeable at the beginning.

(An article regarding George Vernon and Rita’s sister Inez

in concert from the London Times 1902.Q How did you finally get off the ship?

A My brother-in-law took hold of my hand, and I took hold of Mr. Frohman, and we went out through the door on to the deck, and the water swept me away from my brother-in-law and from Mr. Frohman, swept me with such force that my buttoned boots were swept off my feet. I was struck under the water. I sank down twice. When I got up again there was an upturned boat on which I put my hand and clung to…the boat I clung to had canvas on it, and as a great many other people were clinging on to it we were sinking, and then came from under it a collapsible boat that carried away the extra people. We remained out there for three hours and a half, and were picked up by a Welsh collier.

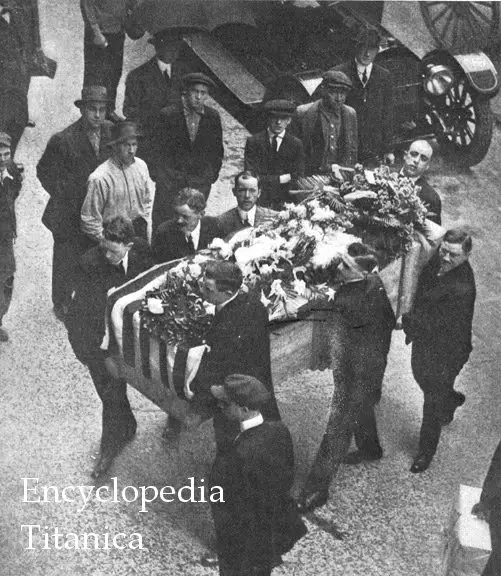

Funeral of Charles FrohmanQ Was this lifeboat you clung to a regular lifeboat or a collapsible boat?

A It was a regular lifeboat.Q When you went over the side was the water up to the deck?

A It was the water that swept me away.Q Water came on the boat deck?

A Yes.Q That part of the ship was down practically at the water’s edge?

A Oh, it had already sunk; it was the water coming up, you see.Q The lee side was under water then?

A Yes.Q On what part of the deck were you?

A I was in the middle of the deck.Q In the middle from side-to-side?

A In the center near the elevator; near the lift.Q From side to side?

A Yes; then we went out on to the deck and saw the ship was sinking right away, and waited til; the last moment, you see, and then she sank…

In Queenstown, Rita was in the company of Amy Pearl, who lost two of her four children, Maude Thompson widowed by the disaster, and the injured Lady Marguerite Allan who lost both of the daughters who accompanied her on the voyage.

Although not mentioned in her account, it is likely that Miss Jolivet was also in the presence of survivor Beatrice Witherbee, who lost her mother and son in the disaster.

As related in part one of this article, Beatrice was moved from a “nursing facility” in England to the Jolivet residence, where she met Rita’s brother whom she married in 1919. Rita remained in touch with Amy Pearl for a time, and Amy’s daughter recalled that the two often visited one another. She may also have kept in contact with Lady Marguerite Allan, for she married Sir Montagu Allan’s cousin, James Bryce-Allan in the 1920s. A private film of the wedding was made and has survived, unlike most of Rita’s commercial output

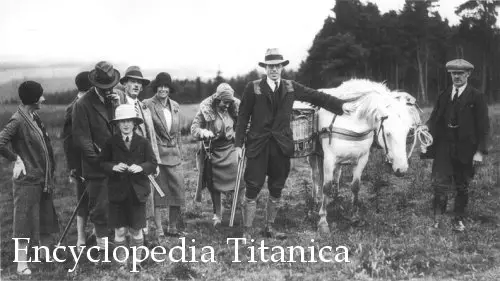

Scotland, early 1930s

Left to right: Trixie Witherbee Jolivet, Lawrence Jolivet, Alfred Jolivet, Lady Jose Bebb,

Count Henri Gaillard, Gladys Lee, Rita Bryce-Allan, Jimmy Bryce-Allan.

(Lawrence Jolivet)

“We all liked Jimmy. It was Rita my parents found annoying…..”

— Lawrence Jolivet, asked if his parents got along with The Bryce-Allans, 2005.

Her career as a performer tapered off by the mid 1920s, and thereafter she concentrated on her work as a critic, and on her social obligations and travel. James Bryce-Allan had been surprised to discover after their marriage, that Rita was quite a bit older than she had claimed to be, but the pairing of the reserved Scotsman and the flamboyant English-raised French actress proved to be successful and lasted until his death. The friendship between Rita and Beatrice Witherbee Jolivet became strained over the years, due in part to their greatly differing personality types: Rita’s habit of introducing her brother Alfred, nearly a decade younger than herself, as “my older brother” with its implication of “… and his older wife” annoyed Beatrice and her husband a great deal.

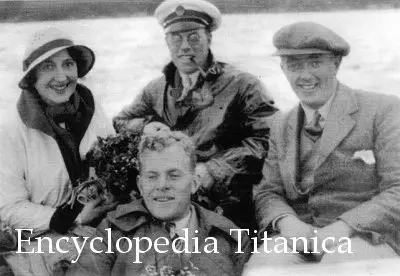

Rita Jolivet and her husband, James Bryce-Allan aboard their yacht, the Scotia in the mid 1930s.

The captain, who is the gentleman on the right side of the frame, ironically bore the last name Turner.

(Courtesy Lawrence Jolivet)

Rita died in surgery on March 2, 1971 after being injured in a fall while dancing. She had been demonstrating that she could still dance a jig, when she stumbled and broke her hip. Beatrice Jolivet, upon learning the details of her sister in law’s fatal accident remarked “Oh well, she would go like that.” True to form, Rita’s last words were a lie about her age; “I’m only 77,” although she was actually in her 80s. One of her final films, a surreal French comedy by the title of Phi-Phi (1926) surfaced a few years back and was screened in Europe to critical acclaim in 2003, which doubtlessly would have pleased her.

|

| Beatrice Williams with Mr. Lane of the Royal Gwent Singers (Daily Sketch) |

|

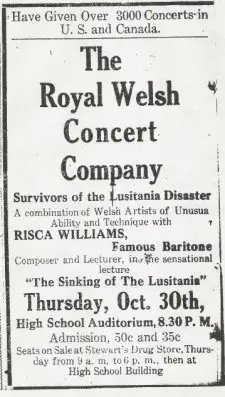

John Preston-Smith was a member of the Royal Gwent Singers from Wales, but he was not Welsh. He was born in Southbanks, Yorkshire, but as his wife Anne later noted, “He was connected with the ‘Welsh Singers’ for so long, he seemed one of them.” He and the others had been touring the United States, performing in the principal cities and giving special recitals before President Wilson, Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller. They remained in Brooklyn during the March and April, performing in various churches.

There were 14 singers and all, and they were to have sailed back to England on the Transylvania, but 9 of them transferred to the Lusitania. Dewi Michael explained why. “Some of us, too, thought as a matter of fact, that it would not only be more expeditious but safer to travel with the Lusitania.”

Survivors remembered the choir standing at the rail when the ship sailed. They sang, “Star Spangled Banner” and “Wales, my Wales.”

Reverend Henry Wood Simpson had brought along his viola and violin and provided musical accompaniment to the singers when they performed.

The gentlemen in the choir were called upon during the ship’s concert to entertain the passengers. Dewi Michael later recalled the final song of their conductor George Davies. “He was so loved by us… Strangely enough, the last song he sang was ‘Down with the Salamander.’ A strange coincidence that he should have been singing that when he himself would be going down. He sang it well too; I fancy I can hear his beautiful bass voice now.”

The group was at lunch when the ship struck. They stayed together only a short time, and in the confusion, became separated. Preston-Smith was with Beatrice Williams and they ran back downstairs to get lifejackets. Miss Williams was placed in a boat and told to get out again. “The ship was listing so heavily,” she said, “that I had to jump. Mr. Preston-Smith jumped with me and I was picked up and put on a raft.”

The end of the Lusitania came quickly and Preston-Smith noted

“I got washed away about 100 yards, and then I got a hold of deck chair on which I rested for about 20 minutes before I got on a raft. I helped four others to get on it, but the raft was over-loaded and began to sink so I took to the water again, as I was the only swimmer. I got on a little iron tank, and held onto that for two hours, though it toppled over several times… It was a Yorkshire man who pulled me out of the water at last, and for half an hour after being rescued, I was utterly helpless. They also pulled out an Irishman named Doyle, who was singing Irish songs in the water. He had gone quite daft. We pulled six women and three men out of the water, and two of the women subsequently died. Whilst swimming towards the raft, and almost done up, a woman swept past me propped up with lifebelts and deck chairs all around her. She asked for assistance, but I was too done up to help her, because by now I had lost the use of my legs. She said she was about done too, ‘but, I am going down like a Briton,’ she added. Just then, a raft came by and picked her up, and all the boys on the raft gave a hearty cheer. They just went crazy with joy at being able to rescue her.”

Royal Gwent survivors photographed in Queenstown

William ‘Spencer’ Hill claimed in his account that he, Thomas ‘Risca’ Williams, William Gwynn ‘Parry’ Jones, and John Preston-Smith managed to get to the same raft and began singing, ‘Praise God from Whom All Blessings Flow.’ “I don’t think I have ever heard it sung with more feeling,” he said. “Then some of the women began to cry and as that would not do, we struck up ‘Tipperary,’ and then they laughed.” Spencer Hill may have been misquoted or was incorrect in claiming that John Preston-Smith was with them. Preston-Smith was one of 11 people rescued by the Heron and brought into Kinsale. These people included Julia O’ Sullivan, Joseph Thompson, Stanley Critchison, Michael Doyle, Charles Hotchkiss, Frank Toner, Vernon Livermore, Cornelius Horrigan, Harold Rowbotham, and Fred Bottomley.

Royal Gwent Singers (among them John Preston-Smith):

a post 1915 publicity photo

(Michael Poirier)

Following his rescue, John Preston-Smith married Anne and continued to tour with choir; sometimes together and sometimes in smaller groups. As late as the 1930s, Risca Williams gave lectures on the group’s survival. The Preston-Smiths moved from Wales to Racine, Wisconsin in the 1940s. He had a stroke a few years later that left his right side paralyzed. When Adolph and Mary Hoehling were writing Last Voyage of the Lusitania, they contacted the couple. Anne dutifully sent the answers to any questions with which John could help and provided clippings about her husband’s involvement in the disaster. She also noted that they were still friendly with Beatrice Williams Harper, whose life John had helped save, and also with ‘Parry’ Jones. John Preston-Smith passed away on February 9, 1957 and was buried in Mound Cemetery in Racine. Titanic survivor Jennie Hansen is buried in the nearby Calvary Cemetery. Anne Preston-Smith moved back to Wales and died in 1973.

|

| Millie Baker |

Millie Baker was another Lusitania passenger with show business aspirations. She had not, at age 27, achieved the same level of success as Rita Jolivet, nor had she garnered favorable reviews to compare to those of Josephine Brandell, but she had completed several years of schooling as an opera performer in France and was hoping to make her debut at the Opera Comique.

She died in the disaster, and with her went her aspirations and whatever talent she may have possessed. Millie was the sole support of her foster mother with whom she had enjoyed a cordial relationship, and to whom her $2000.00 life insurance policy was left. Mrs. Baker was granted $15,000.00 by the Mixed Claim Commission, $14,800.00 of which covered the estimated value of Millie’s lost jewelry and wardrobe.

There was a side of Millie not preserved in the official record, and perhaps not known by her grieving foster mother. The unknown opera student was traveling in a very select circle, as the only quote we have located regarding her aboard the ship attests:

Presently, a party of us came together: Vanderbilt, C.F. Williamson, a dealer in antiques of Paris and a great personal friend of Mr. Vanderbilt; Edward Gorer, an art dealer of Bond Street; Mr. Slidell, a newspaper correspondent; and a lady known to us all, who lives in Paris, Miss Baker…

~George Kessler