Double Jeopardy – Lusitania’s Unique Victim

The astonishing story of the woman whose body was twice claimed by the same German submarine.

THEY pray for night, craving the hours of darkness, these passengers who dread the day.

Long agonies on the exposed sea are behind them. The sun that has searingly spotlighted their presence, as if in wanton enticement of the enemy, finally seems ready to abandon its cruel game. The torturing orb sags toward the furthest edge of sight.

Hesperian, whose very name is of the west, heads for the golden horizon. But more precious than gold – for those aboard – will be the sacred, grateful shades of night.

Only one person aboard has not eyes for the dying of the light. That person has long since yielded to relieving oblivion. Mrs Frances Washington Stephens is already dead.

This is the story of the woman whose body was twice claimed by the same German submarine.

The U-20 took her life on the Lusitania in May 1915.

Embalmed, casketed, her remains were embarked on the Hesperian. And in September 1915, the U-20 sank her again.

There is no seafaring parallel for such a coincidence.

In comparison, the apocryphal story of the supposed journey of the coffin of vagabond actor Charles Coghlan from Galveston to Prince Edward Island is but a worthless bauble

This article presents the first public picture of Frances – Mrs George Washington Stephens – the victim singled out sequentially over thousands of square miles of sea by a sole slim slayer.

For the Kaiser!

What’s the Kaiser to her, or she to the Kaiser,

That he should weep for her?

FRANCES, Mrs George Washington Stephens, stands perfectly poised on a staircase, one hand caressing the rail of an ornately-wrought balustrade, the other dripping gemstones by her side.

FRANCES, Mrs George Washington Stephens, stands perfectly poised on a staircase, one hand caressing the rail of an ornately-wrought balustrade, the other dripping gemstones by her side.

Ruched velvet seems to liquefy at her feet. These, too, are effortlessly positioned in a stance of sublime breeding, a single buckled toecap peeping. The face is magnificently impassive, framed by earrings. And the eye is drawn to the neck, the embonpoint, and a waterfall of pearls…

Some make do with a collar, or a choker; the better-off with a necklace, the affluent with an opera – the name for a string of pearls that reaches the sternum. Anything longer is classified as a rope, and that of Frances, Mrs George Washington Stephens, plunges off the scale.

Widow of the wealthy George W. Stephens of Montreal, Quebec, the treasures of the sea adorn her chest.

***

Born Frances Ramsay McIntosh, the eventual U-20 victim (twice over) grew up far from the madding crowds that seemed to endlessly contend in the Old World.

The daughter of Nicholas Carnegie McIntosh, of Edinburgh, Scotland, little is known of her early life except that she lived a demure existence in Montreal in the relatively straitened circumstances imposed by her station in life.

Nicholas was a cabinet–maker by trade, which provided enough, but never monetary excess. He and a certain Margaret Brown were married in July 1836, at St. Gabriel’s Presbyterian Church in the city.

The bride’s father, Thomas Brown, had fought with the Cameronians at Waterloo in 1815, was wounded and put on half–pay. He was gazetted Captain, and had come to Canada after his own marriage.

Frances – later Mrs George Washington Stephens – was born to Nicholas and Margaret McIntosh in January 1851, reportedly in Edinburgh, while her father was on a nostalgic trip en famille to his birthplace. There was already an older child to the union, Elizabeth.

Back in Canada, the two McIntosh sisters grew up in humdrum harmony. But a breath of something approaching scandal – or at least tittle-tattle – was created when, at the age of 27, Frances chose to marry her dead sister’s widower.

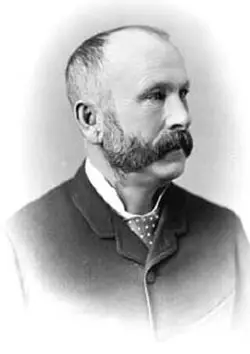

Elizabeth McIntosh had wed, in 1865, one George Washington Stephens. This was a man, already wealthy, whose (obviously patriotic) father originally came from Swanton, Vermont.

Harrison Stephens had crossed the border to try his luck in the Dominion in 1828, and George W. was born to his wife Sarah four years later in Montreal.

The young G.W. went on to study law at McGill University, being called to the Bar in 1863 at the age of 31. At an early stage in his career, Stephens’ profile was nationally enhanced by winning a case that established the validity of native marriages.

After some years of lucrative practice, G. W. Stephens broke off his professional career to administer his father’s extensive estate, and to concentrate on his own burgeoning private interests, including huge tracts of land and property.

Politics fascinated him however, and the good burgher was elected an Alderman at the first time of asking in municipal elections in 1868. He kept his seat for over 20 years, becoming known to the Press as “The Corporate Watch Dog,” such was his vigilant anti-trust eye.

In the meantime his first wife died, but the close relations with his in-laws would provide him with a ready-made replacement. The young Frances McIntosh was married to George Washington Stephens in 1878, the age gap a mere nineteen years.

George Washington Stephens and Frances McIntosh

George now switched from city to provincial politics, and in 1892 swept a seat in the Quebec legislature by a large majority. He later entered Cabinet as a minister without portfolio. In 1896 he introduced a Bill that demanded the covering-up of increasingly decadent theatre posters. It was passed.

A long-time Montreal luminary and paragon of all that was virtuous in life, art and responsibility, G. W. himself passed away on June 20, 1904 at the age of 71.

He was cremated at Mount Royal cemetery, this man who had wed two McIntosh sisters. In that respect, fortune had indeed stuck twice.

***

FRANCES was aged 64 on the Lusitania.

The widow of the pearls was embarking on the sea, long known to mariners as the great grey widow maker, to be with her family once more.

Mrs George Washington Stephens – as she continued to travel by, under the polite protocols of the time – may no longer have had her husband. But she did have her son.

Lieutenant Francis Chattan Stephens was a member of the Montreal Stock Exchange who had his own stockbroking firm of F. C. Stephens & Co. Yet he had volunteered to fight in the Great War.

Mrs George Washington Stephens was taking the Lusitania in order to be with him in England.

|

| Chattan Stephens |

|

| Hazel, John and Frances |

Chattan Stephens was a married man, the father of two children. His had been a society wedding, to the famed beauty Hazel Beatrice Kemp, who was the daughter of a noted Toronto politician, later knighted Sir Edward Kemp.

The fact that Kemp had been, since 1914, Canada’s Cabinet Minister for Overseas Military Forces, need not have weighed on the son-in-law’s mind. Chattan Stephens had already been an army reservist before war began, and would not be found wanting. The stockbroker would do his share.

He was given a commission as Lieutenant in the Canadian 13th Battalion, which shipped to France in support of the ‘mother country’ as part of the British Expeditionary Force. Hazel followed him to England, where the battalion was initially stationed for further training and mission orientation. She rented a house in Sunningdale, Berkshire, close to London.

Hazel had brought with her one of their children, named Frances in honour of her paternal grandmother, Mrs George Washington Stephens, perhaps as a gesture to ease the fresh pain of widowhood. Their other child, son John, remained at home with Granny.

The Canadian infantry duly went to France, but Captain Stephens was not long on the Western Front when he developed what was described as trench fever.

He was taken out of the line and sent to No. 2 Red Cross hospital in Rouen, with news transmitted to Hazel in Sunningdale. Instead of the Captain’s health improving, it soon worsened and he developed endocarditis, an inflammation of the membrane lining the interior of his heart. This was very serious. A decision was taken to evacuate him to England.

With her son facing months of painstaking recuperation, and Hazel already with her hands full, the senior Mrs Stephens took the fateful decision to sail for England from Canada to do what she could for the couple. Besides, she took an annual trip to Europe…

She decided to bring with her baby John, so the family could be entire for the first time in months. It was a move, she little dreamt, that would sunder the unit completely.

Needless to say, these two did not travel alone. Mrs George Washington Stephens would embark with a mini-entourage. The servant who made the bookings returned with the news of cabin assignments.

The whole party would be in first class, Mrs Stephens and her maid (Elise Oberlin) in Cabin D-5, Master John Harrison Chattan Stephens in D-9, accompanied by his nurse, 35-year-old Caroline Milne, of Liscard, Cheshire, who was secretly looking forward to seeing England again.

At the time the Lusitania sailed, Captain Stephens was in a hospital ship en route to a military hospital in England. He would end up at Larkhill, on the Salisbury Plain, where it was immediately ascertained that his heart had been seriously damaged.

Hazel was getting the news that her husband would likely remain a semi–invalid for the rest of his life at the same time that her mother-in-law’s passenger vessel approached the southern coast of Ireland. How it would cheer up Francis to see his son again!

Captain Walther Schwieger kept the great steamer in his periscope sights as an unbearable tension gripped the men inside his own frail craft. At the optimum moment he cried out a single command.

Feuer!

***

The following account, by passenger survivor Frederick Orr-Lewis, is generously transmitted by researcher Mike Poirier –

“We had a table by ourselves, composed of Lady Allan, Mrs. G.W. Stephens, Miss Dorothy Braithwaite, Gwen [Allan], Herbert Holt’s son [William Robert Grattan Holt], Anna [Allan] and myself.

“We finished our luncheon and went upstairs to the lounge, had our coffee and were smoking our cigarettes – when like a bolt from the blue, a torpedo struck the ship… We rushed out on deck at once and I got them all together, put lifebelts on them… so there was nothing to do but wait, when in the twinkling of an eye, she took the most awful dive and we all went down with her.

“I had Gwen by the hand, and Lady Allan had Anna, and the two maids were next, and Mrs. Stephens with Chatham’s [sic] baby. Miss Braithwaite somehow got separated from us. How far we went down or what happened know one will really tell.

“The next morning I was asked to go and identify some of the bodies and the first one I saw was Mrs Stephens.”

***

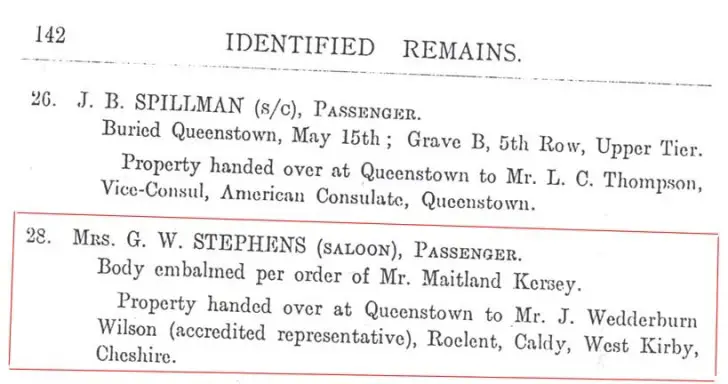

THE body of Frances (No. 28) was the sole one recovered among the first class quartet. All the others were drowned, their remains never being seen again – infant grandson John, his nurse, Caroline Milne, and the maid, Elsie Oberlin.

Chattan’s child, Baby John, must have been somehow swept out of the arms of Mrs Stephens, who was last seen on the port side on the Lusitania as the boat deck was going under water.

Chattan’s child, Baby John, must have been somehow swept out of the arms of Mrs Stephens, who was last seen on the port side on the Lusitania as the boat deck was going under water.

Of the four in the party extinguished, John’s face best epitomises the 1,198 potentialities snuffed out by the obdurate waste of war.

Mrs Stephens’ body appears to have been recovered on the night of May 7, 1915, by the flotilla of various craft that went to the rescue. Likely boat-hooked to the side of a trawler or a flower-class sloop, it would seem she was wearing one of the Boddy patent lifejackets.

Certainly the rope of pearls was still around her neck, as if the noose of Neptune.

Brought ashore at Queenstown by ghastly torchlight that night, it was available in the makeshift morgue to be inspected by Frederick Orr-Lewis the following morning.

The other angelic face from the photograph of mother Hazel with Baby John is that of young Frances Elizabeth Stephens. She is now 95 years old (2007).

The other angelic face from the photograph of mother Hazel with Baby John is that of young Frances Elizabeth Stephens. She is now 95 years old (2007).

“John Harrison [Chattan Stephens] who also drowned was my baby brother, some 18 months younger than me,” she recalls. “This terrible event has always haunted the family memory.”

“My Grandmother was very fond of pearls and had a famous and lengthy string, which she was wearing when she drowned. The family lore is that it was stolen from her body, as it was missing when she was first laid out ashore. However, when my uncle returned to check the body the next day, it had been restored.”

The pearls featured in the photograph are now in the possession of a centenarian cousin of Frances in England. Made exclusively of oyster pearls (mussels also produce pearls), the rope is excessively valuable – even if pearl values have fallen since the early years of the century when an iridescent collection was often prized beyond diamonds.

The story of the temporarily ‘stolen’ pearls is unsupported by the known facts, which are open to the interpretation that such a valuable set was securely locked away pending identification of the remains on which they were found.

Mrs Stephens’ body was embalmed, as were most of the North American bodies of the wealthier class in anticipation of their return to that continent. The records show her casket was transferred to Liverpool by Mr Wedderburn Wilson, who was the husband of a relative.

According to family lore, the baby’s mother had gone to Euston station to meet Lusitania survivors, hoping against hope for the escape of her son in particular.

In the years to come she would suffer further tragedy. Lieutenant Stephens, robbed of the consolation of seeing his son, devastated by the boy’s death, would live only another three years.

His heart critically weakened, Hazel’s husband died at home in Pine Avenue, Montreal, on October 16, 1918, a victim of the great influenza epidemic.

Hazel, born in 1889, married again in 1920, and died in 1961.

***

THE above photograph shows the body of an American victim of the Lusitania being landed in New York.

The reason for the delay in returning the embalmed remains of Mrs Stephens is not known, it having apparently been decided at an early stage that she should be interred in Mount Royal cemetery in Montreal, where her husband had been cremated.

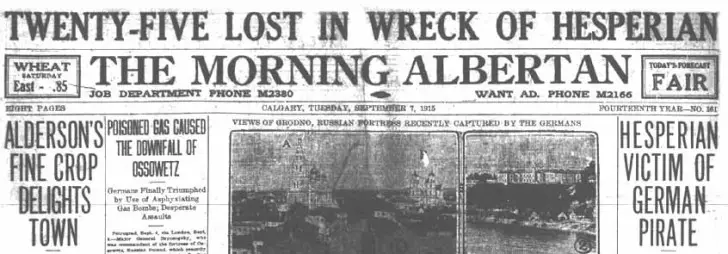

Her metal casket, boxed in a wooden crate, was finally booked aboard the 10,920-ton Allan Liner Hesperian for the Atlantic crossing. Captain William Main would take charge of the voyage.

Six hundred passengers crowded aboard Hesperian, including many wounded Canadian soldiers from the Western front – a touch of irony in Mrs Stephens’ case, since a wounded Canadian soldier had drawn her to Europe in the first place.

The vessel, now under charter to the Canadian Pacific line, was not long out of Liverpool when she was torpedoed 85 miles southwest of the Fastnet rock.

It happened on September 4, 1915 – less than a week after Count Bernstorff, the Imperial German Ambassador to the United States, had assured Washington (following long-running outrage over the Lusitania destruction) that ‘passenger liners will not be sunk without warning.’

But that happened in the case of the Hesperian. The longed-for night did not bring safety for those aboard – instead it provided a convenient cloak for Schwieger’s U-20.

Mrs Stephens’ corpse was thus sunk by the same submarine which had first taken her life on the Lusitania.

Indeed the Hesperian, with the casket presumably still in its hold (unless broken free), lies within the same vicinity as the Lusitania wreck, as if fate had ordained it so.

Detailed accounts of the Hesperian sinking can be read here:

|

“Canadian wounded on board”

|

“Attacked in the darkness”

|

“The sinking of the ship”

|

“Vivid story of the torpedoing of the Hesperian”

|

In retrospect it seems strange that a Canadian shipping line could ever have commissioned a vessel to be called the Hesperian, given the familiarity of practically every North American with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 19th Century poem, ‘The Wreck of the Hesperus.’

Who would wish to board a sound-alike for a celebrated shipwreck?

It can hardly have been coincidence, therefore, that many newspapers chose to refer in their headlines to the ‘wreck’ as distinct from the torpedoing, or sinking, of the Hesperian. A ship’s wrecking properly refers to the elements, rather than a coldly planned destruction.

And yet one fragment of Longfellow’s work seems distinctly apposite:

Down came the storm, and smote amain

The vessel in its strength;

She shuddered and paused, like a frighted steed,

Then leaped her cable’s length.

But the Hesperian did not immediately sink, although she wallowed low in the water. Nor did the U-20 fire more than one torpedo, as she had not fired more than one at the Lusitania.

A group of wary British vessels at length appeared on the scene, summoned by SOS. The Hesperian, a skeleton crew and Mrs George Washington Stephens still aboard, was taken in tow for Queenstown. She never made it, sinking some 37 miles from land.

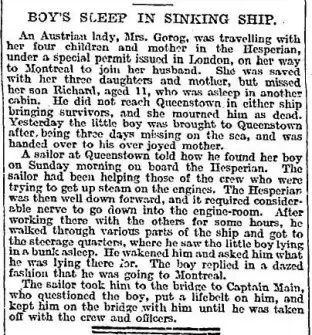

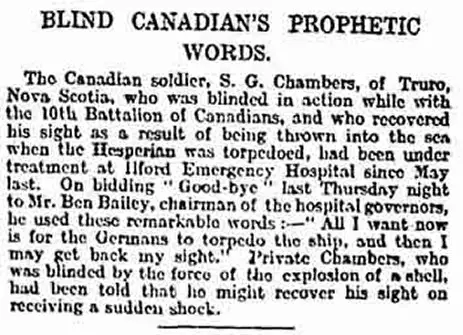

The Hesperian survivors swarmed from rescue vessels onto the quays of Queenstown, including one man who had been blinded on the Western Front only to have his sight restored by the shock of the explosion.

His fortuitous tale is met by another – that of a boy who was left behind, sleeping in his bunk, throughout the emergency.

But the most extraordinary tale of all is that of Mrs Stephens, whose metal casket lies on the seabed – perhaps enclosed by a ship, perhaps not – within a short sea distance of the wreck of the great passenger steamer that originally carried her.

It may even be that her sarcophagus now plays host to a bed of mussels, perhaps one of them containing a pearl… but this is a story that needs no adornment. More prosaically it might be observed that her wartime assassin, Walther Schwieger, shares her unhappy fate.

He too lies at the bottom of the sea in a steel surround, that of the U-88, his submarine command subsequent to the U-20.

A stranded U-boat of the U-20’s class

Two years and one day after the Hesperian sinking, the U-88 struck a mine somewhere off Terschelling island, northern Holland. She sank with all 43 hands.

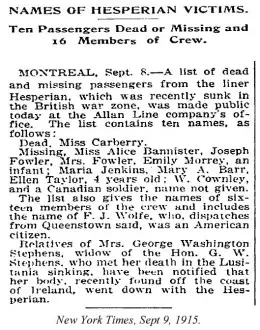

A short story in the New York Times recorded Mrs Stephens’ presence on both the Lusitania and Hesperian, although it was not by then realised that both ships had been sunk by the one submarine.

(Author photograph)

Between the two, in the intervening four months, the U-20 had only sunk three vessels – the Ellesmere, Meadowfield and Roumanie, all relatively small fry, which makes the coincidence seem all the more amazing.

Only a panel on a tomb in Mount Royal cemetery in Montreal now commemorates Mrs George Washington Stephens’ passing:

The author wishes to acknowledge the assistance in the preparation of this article of Mrs Stephens’ granddaughter, in younger days a regular tourist to Ireland where she has visited both Kinsale and Cobh (Queenstown). In remembrance.

Life goes on:

Frances Elizabeth Stephens in 2006, left, with her daughter

© All rights reserved. No pictures or any portion of this article may be reproduced in any form whatever without the express prior permission of the author. Senan Molony 2007.