Ceramic : The Sole Survivor

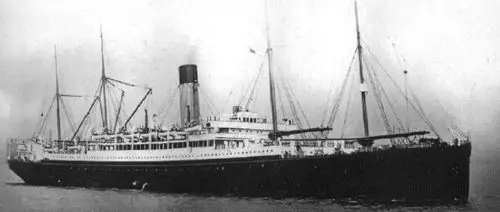

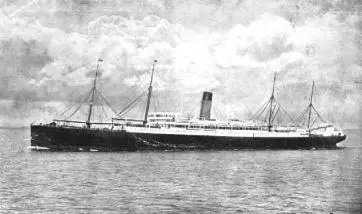

By 1942, the White Star Line had merged with Cunard, and many of its ships had been sold off or sent to the scrapyard. Among the former was Ceramic, launched in 1913 and for many years the largest vessel in White Star Star’s Australian service. Transferred to the Shaw Savill Line upon the merger, Ceramic found herself in a nightmarish World W orld War II drama. Author Clare Hardy has just self-published a book, Ceramic: The Untold Story Story, which features the account of Eric Munday, the sole survivor of the disaster. Ms. Hardy has detailed some of the challenges she faced in writing the book in this article.

“… On November 23, 1942 [the White Star liner Ceramic] left the Mersey for Australia, independently routed, with 378 passengers. Her subsequent, complete disappearance was at first little publicised at home, due to the general censorship of shipping information, and the Admiralty assumed that she had been sunk without survivors from the 500 or so persons on board. It was learned a long time later that she had been torpedoed and sunk on December 6 in latitude 40 deg. 30 min. N., longitude 40 deg, 20 min. W, and that one survivor, a sapper of the Royal Engineers, had been picked up by the U-boat and taken to a German prison camp. The full story, as far as I know, has never been published.” — J. H. Isherwood, Sea Breezes, “Steamers Of The Past: White Star Liner Ceramic of 1913,” November 1963.

The passage above leapt out at me in the early stages of my research into the fate of the SS Ceramic. It was true — the full story had never been published, but I had tracked down Eric Munday, the sole survivor, with relative ease, and he had met me to talk about the circumstances of the sinking, which had claimed the life of my grandfather. Moreover, he had left his diary with me, written in pencil on some scrap paper and a small pocket book that he had kept from the time of his rescue by the U-boat that had sunk the Ceramic, and had returned to find the captain — or any survivor — in the stormy seas that blew up after the ship was sunk.

Eric’s diary took me, the reader, into the belly of U-515 as she finished her tour of duty before returning to Lorient in January 1943. I experienced Christmas with Eric and the crew, complete with carols, a Christmas tree and cream made from butter that had been salvaged from another wrecked ship. With Eric, I experienced depth charges from our own side until returning to the relative safety of the U-boat base, and onward to a prisoner of war camp in Ober Silesia.

Well, not literally, but the immediacy of firsthand accounts struck me with their ability to bring history back to life, and I thought this would be the way forward in compiling a history of the SS Ceramic, to fill in a gap, and provide the answers that relatives and friends of those who died might find in its pages.

Eric was more than willing to allow me to transcribe his diary and the letters he wrote and received from Stalag VIIIB, which took up the story once his diary entries waned over time.

I was also reading a number of secondary sources at that time, and the discrepancies and inaccuracies were frustrating. I wanted to talk to those who had been there and who could tell me exactly what had happened.

But Eric was the only survivor, so I only had one person’s experience. Then I realised, of course, the U-boat crew had been there, and could tell me what happened from the other side. With the help of Jak Showell, a renowned author on the U-boat war who represents the U-boat archive in the UK, I was able to get in touch with Walter Raksch, organiser of the annual reunion for ex-crew of U-515. I was invited to attend in 2001, and bring Eric for a reunion 60 years after his rescue. We were accompanied by Eric’s wife Joan and my sister-in-law Helen, who is fluent in German and was able to interpret for us. A 1914 postcard.

A 1914 postcard.

My diary account of this time, and the accounts that were given to me by the crew, make up a chapter of the book, and the fate of the U-boat commander Werner Henke is also covered by way of firsthand accounts from those who were there.

Many poignant letters from relatives to Eric Mun-day after the war are included as extracts, and there is a 70-page list of those who died. The sense of loss is at times so intense that the book may be hard to read (it was certainly hard to write, and took me seven years), but it was important to me that it should accurately reflect the human cost in a respectful and not a gratuitous way.

I did not wish to write a book that was overwhelmingly heavy with tragedy, however, and the Ceramic’s career before her loss had been anything but somber. Indeed, when she entered service in 1913, she was the jewel in the crown of the White Star Line’s Australia service, the longest and fast-est in her class, with masts that barely passed under Sydney Harbour Bridge, her arrival in port heralding much excitement amongst young and old, anxious to welcome her from a long voyage from the far side of the globe.

Left: Right: Ceramic passing under the Sydney Harbour Bridge, then under construction.

Left: Right: Ceramic passing under the Sydney Harbour Bridge, then under construction.

During the First World War, which broke out just a year after her maiden voyage, the Ceramic was snapped up by the Australian government and used as a troop transport. This period was not without incident, but she emerged unscathed for her glory days, the halcyon inter-war years, when she operated on her original designated route between England and Australia via the Cape. Photographs from this period capture a carefree time of adventure and new beginnings.

During the inter-war period, the Ceramic was taken over by Shaw Savill & Albion and refitted. Her accommodation remained single-class, but was quite comfortable for the period.

SS Ceramic: The Untold Story contains many diary accounts and memoirs from the Second World War, when the Ceramic stayed on her customary route, but also transported troops between continents. The reader can take a trip around the world at this point, dodging U-boats, basking in the sunshine of the tropics and tasting the salt spray of a lashing in storm-swept waters. In 1940, the Ceramic was in collision with the Andrew Weir Line Testbank, and a number of previously unseen photographs of this event were unearthed in South Africa and published for the first time in the book.

The events of the Ceramic’s last journey are told through the convoy report of escort ship HMS Broadway. It was only after her detachment from ON149, when her speed was considered sufficient to keep her out of trouble, that the vulnerability of an unescorted ship carrying 656 passengers and crew — men, women and children — became tragically apparent. Sailing into the jaws of U-515, there was no rescue vessel to pick up survivors until weeks later when the storm that blew up overnight had long decided the fate of the ship’s complement.

The events of the Ceramic’s last journey are told through the convoy report of escort ship HMS Broadway. It was only after her detachment from ON149, when her speed was considered sufficient to keep her out of trouble, that the vulnerability of an unescorted ship carrying 656 passengers and crew — men, women and children — became tragically apparent. Sailing into the jaws of U-515, there was no rescue vessel to pick up survivors until weeks later when the storm that blew up overnight had long decided the fate of the ship’s complement.

As a new author, I was unable to secure a publishing deal, and the result is that SS Ceramic: The Untold Story is self-published in a limited edition of 600. It is published in paperback, and its 572 pages contain numerous black-and-white photographs, diagrams and illustrations spanning the 30-year period. It will therefore be of interest to anyone with an interest in shipping, irrespective of any particular connection to this ship.

The first copies have been signed by Eric Munday, the sole survivor of the Ceramic, and by myself. Ordering details may be found on my website www.ssCeramic.co.uk.

This article first appeared in Voyage: the Journal of the Titanic International Society.