Morro Castle, Mohawk and the end of the Ward Line : Part 2

Everything had been burned away

Reginald Roberts of Yonkers, New York, had graduated from Roosevelt High School and entered Columbia in New York City. However, whether it was because of wanderlust or depression era hard times, he withdrew from his studies and went to sea for three years, spending one year sailing around the world, and two years aboard the Morro Castle as an oiler. He returned to Yonkers a day after being rescued, and met the press with his parents:

I first learned of the fire about 3:10 when smoke came into the engine room through the ventilators. There was no fire in the engine room. I notified the engineer in charge and went back to my post. I’m an oiler and I have to be on close guard. I was then ordered to go above and notify the other engineers.

I went to the elevator and went up, but when I got to B Deck I couldn’t open the door. Then the lights of the car went out. I couldn’t move it. I pressed the button but she wouldn’t go down.

Roberts struggled with the lever to open the door, but it seemed jammed. Finally, the elevator sank back down the shaft:

She went down slowly. I went to the officer and told him I couldn’t get out. Then I went back to my post.

We tried to continue moving the ship but it was no use. At last Third Engineer Stamper told us to leave the engine room. We went through the shaft alley and came out on D Deck. The shaft alleys are long runways though which the driving shafts run to the propellers. There is just barely room for men to squeeze through them. There were hundreds of people huddled at the stern. I saw that many passengers were jumping off B and C Decks into the sea rather than take their chances on being suffocated. The smoke was choking everyone. But there was absolutely no panic. Everybody was excited, of course, but everybody seemed to be trying to avoid panic. They jumped into the sea every few minutes. I was nearly suffocated until I wrapped a wet rag around my face and got close to the floor where the air was better.

There was no sign of rescue ships. In the distance we could see the lights on land. Everybody was looking for ships. At daybreak the people grew quieter. Everybody though we were going to be saved. We could see rescue ships drawing near. People kept jumping into the water and forming groups waiting to be picked up.

Finally we smashed into an unoccupied cabin and I got a life preserver. Then the deck we were standing on began to burn so we jumped. The ship was just a hollow shell. Everything had been burned away. We couldn’t stay any longer.

Roberts omitted any details of his experience in the water, saying only that he “floundered.” He was picked up by a lifeboat from the City of Savannah.

They were short handed in the lifeboat because they were sending out so many boats. I took an oar with another fellow and we rowed in near the Morro Castle. We picked up five women from the water.

Reginald Roberts was taken to Marine Hospital in New York, where examination showed him to be “over tired” but otherwise uninjured. He was reunited with his “frantic” parents the following day, and posed with them on the lawn of their home wearing the life jacket in which he escaped from the Morro Castle.

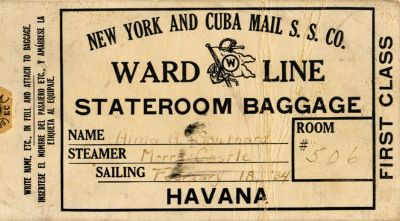

Morro Castle Baggage Label

Police officers James Butte and Charles O’Connor, of the Lawrence Avenue Station in Brooklyn, chose the Morro Castle for their respective yearly vacations. Both survived, with O’Connor returning to Brooklyn suffering from immersion and shock, and Butte with eyes damaged by exposure to smoke. A portion of his 1934 account survives:

I was awakened by a knock on the door. “Jim, there’s a fire” a voice shrieked. O’Connor and I jumped from our berths and dressed. We donned life preservers and ran outside- we were on C Deck and the noise was something awful.. Men and women dashing here and there.

Charley and I ran up to B Deck with several members of the crew trying to bring down panicked passengers.. Flames were sweeping towards us from both sides. On the way down I lost site of Charley- I haven’t seen him since.

A girl came up to me and asked me to giver her my lifebelt. She was crying and at the same time trying to hold back the tears. I gave her my belt and the second engineer of the ship- whose name I do not know- did the same for another girl. Many of the passengers had left their cabins forgetting to put on their lifebelts. And when they realized it, it was too late to return for them- the staterooms were full of smoke and fire.

We had to heave a number of passengers overboard because they were too scared to jump. Meanwhile, members of the crew ran up to B Deck to get deck chairs. They hoped to throw the chairs into the ocean so that swimmers could cling to them.

A sad coda to this tale of heroism was provided by passenger Martin Renz (1891-1967). The Brooklyn house painter disembarked from the Monarch of Bermuda shocked and angered by the death of his wife, Marie. Mrs. Renz, a non-swimmer who was not wearing a life belt was picked up by men determined to “save” her who, despite her protestations threw her overboard, where she immediately drowned beside the ship.

There was no reason for so many women being thrown overboard. It seemed to be a regular practice to throw every woman overboard whether she was wearing a life preserver or not.

A similar fate awaited Mrs. Carrie Clark of Howard Beach, New York. Her husband, William, survived the disaster and gave two brief interviews to separate Long Island newspapers. By pairing them we came up with this account:

At first I wasn’t afraid when my wife and I got the fire alarm. I’ve seen fires on ships before. We dressed fully- I even took my Panama hat and my wife went back for her shoes. But when we went on deck the whole ship was wrapped in flames and I knew it was a goner.

We staggered through the smoke and met an officer who told us the fire was serious. We brought our life preservers but did not know how to adjust them. Someone threw my wife off of the upper deck before I could intervene. If I could only have stayed with her she would have been saved. A rescue boat picked me up almost as soon as I got in the water.

William Weil, of Hollis, Queens, left this account:

It was impossible for us to get to the boats, which were inaccessible on A Deck. The crew fought the flames with thin streams of water, and then when the water failed I saw them try to pound out the flames with the nozzles. There were no lights on the ship, but many of the crew had flashlights which they used to guide us to the ropes.

Considering the absolute darkness, heavy smoke, and frenzied passengers I have no blame to put on the crew. I was awakened by one of them and told to put a ,life preserver on.. As I placed one on my wife, tying it on with a bow knot, one of the crew untied the bow and made three heavy knots.

The Weils jumped separately from one another. Clara Weil, a member of the Concordia Society, died of exposure while awaiting rescue.

Officer William Price made the voyage with his wife. Mary Price, 59, was “in delicate health” and it was hoped that the sea voyage and days spent in Havana would be beneficial to her. The Prices were in the same crowd as officers Butte and O’Connor at the stern on C Deck. Morro Castle legend has it that Price drew his gun to keep a portion of the crowd back until his wife could be lowered safely to the water, though no first person 1934 account stating this has surfaced. According to witnesses, Mrs. Price died as soon as she entered the water, possibly of a heart attack. Her body was identified at the Bellevue Morgue in New York City: William Price survived the fire.

Less fortunate, still, was veteran officer Adolph Kosbothe, of Brooklyn. Both he and his wife, Mary, perished on September 8th: Mrs. Kosbothe was identified by her nephew at the temporary morgue in Sea Girt New Jersey where she had washed ashore on the 9th. Adolph was never found.

Morro Castle Orchestra

Nelson Ruscoe, 37 (1897-1978) led the Morro Castle orchestra. Wrapped in a blanket, his burned foot bandaged, he met the local press at his Bronx residence:

I was awakened by the fire alarm. It meant ‘hit the deck.’ I woke the boys- we shared two rooms- and told them to get dressed and get on their lifebelts. I rushed aft on B Deck to learn the extent of the fire. I saw plenty! I hurried back and told the boys to hurry- that the middle of the ship was an inferno. We thought of the lifeboats and went to B Deck, but there we were stopped by a wall of flame. Other were already on deck-passengers and crew.

We decided to try D Deck aft. As we started, the lights went out. We were in darkness- around us we could hear the screams. The ship was bedlam-smoke and flames were pouring out of the stateroom windows. All of us got aft safely, including one man who fell down the steps and broke his leg, I think.

With flames shooting out of the bulkhead, the crowd became panicky. Some rushed to the rail and jumped overboard. Then I found Al (Alfred Kurland, saxophonist) and Hersch (Harry Herschkowitz, drummer) missing.

In the darkness we could hear bodies hitting the water- we could see nothing but the sheet of flame in front of us.

Then the dawn came. We saw shadows around us. Then we could see them clearly- they were ships. But they could not come close enough. The sea was rough, a gale was blowing and we had rain. From the ships the lifeboats were lowered. Even they could not come close.

Now we could see the water below us. People were there, clinging to the ropes we had thrown overboard in the night. There must have been 40 in the water. None appeared dead.

Then we heard a whistle, and right across our bows came the Monarch of Bermuda. It was just after dawn- we knew then rescue was near. We even cheered. Almost immediately the boats were lowered and came over to us. We slid down the ropes- I guess there must have been 50 of us- to the water and in a jiffy we were picked up together with those who were already in the water. We were drenched to the skin, but we were alive. Instead of dropping ladders to us, the ship hoisted the boats aboard where we were given first aid, hot drinks and food.

An interesting account written by Harry Herschowitz, the drummer with the ship’s orchestra, survives.

I was asleep in my berth below decks when I was awakened by the ringing of the general alarm. I was tired, tight asleep, when it happened.

It was creepy, what with the boat tossing in the storm, fog outside and the dead captain in his cabin. I didn’t like it- it was a strain on the nerves. When I got to bed I was so exhausted I didn’t stay awake a minute. And then came the sound of those bells.

I heard the members of the crew rushing around outside in the corridor. I slipped into my underwear and threw open the door. “Take your stations” was the order. My station was on the Boat Deck. Flames were lapping up the side of the ship. The smoke blew across and burned my eyes. Somewhere along the trip from below I had picked up a lifebelt- I seem to remember tripping over it at the foot of the companionway.

I tried to get to my assigned position through the smoke and flames. Finally a gust of fire swept across that section that almost blinded me. Then I turned my back and went to the opposite side of the deck. The boats there had all been lowered to the water. The davits were empty.

Passengers and crew were jumping over the rail 30 feet to the water. I looked around- that seemed to be the safest thing to do, so I jumped ,too. I bobbed to the surface and swam around.

A woman dropped from the Main Deck, almost on top of me. She was hysterical. Although she had a lifebelt on, she threw her arms around me like a maniac and tried to crawl up on my shoulders. Finally, I quieted her. We were in the water seven hours, floating away from the ship all the time. Then, we were picked up by a fishing boat.

Mrs. Herschkowitz, of The Bronx, a wife of two years, later recalled:

I became panicky when I heard the news. I called the Ward Line but could learn nothing. My brother went to the pier hoping to hear good news, but nothing came. I tried to keep from thinking of the worst, how so many had perished in the flames. Then came a telephone call. A man said my husband was safe at Spring Lake. Then a few minutes later Harry was on the phone. He sounded tired and weak. The said he had been through a terrible ordeal, that he was in the water for seven hours and saw many people perish.

41 year old Alfred Kurland of Sherman Avenue, the Bronx, was not as fortunate as Harry Herschkowitz or Ruscoe Nelson. He had served aboard the Morro Castle as a cello-saxophonist for three years, and had taken a land-based job starting on Friday, September 14th. He opted to make one final voyage and, like most of those lost, died of exposure waiting for rescue. He left a wife, Alma, and two adult children. Also lost from the orchestra was pianist Irving Bradkin. Saved were William Weintraub, violinist; Max J. Bendit, trumpeter, and Julius Rosen saxophonist.