Morro Castle, Mohawk and the end of the Ward Line : Part 2

The Long Swim to Shore

Abraham and Harriet Cohen of Hartford, Connecticut were finishing their honeymoon aboard the Morro Castle. They had married on August 28th 1934, in a ceremony at the bride’s home and departed for Havana four days later. Photos taken on the southbound leg of the voyage, which Harriet mailed home to her mother from Cuba, represent the last known images of life aboard the ship. The athletic young couple swam the six miles to shore together, after escaping from the flaming vessel, and survived to be photographed beaming at one another, and raising glasses in a toast, from their adjoining hospital beds in New Jersey. A few days later, Harriet Cohen wrote this account:

I heard screaming outside our cabin. I rushed to the door, opened it- flames filled the hallway. My husband awakened and we put on our bathrobes. We went out through the flames and finally made our way to B Deck. The decks were filled with people- everyone seemed excited. The smoke hung low and the fumes almost suffocated us.

People were milling and jammed close together. There didn’t seem to be anyone who could keep the people quiet.My husband and I made our way to the railing and decided the best thing to do was to jump. We did. I guess we were scared, but there wasn’t time to think about it.

Once in the water our first thought was to get away from the boat. There were other struggling around us in the water, but after we got started and swam a while we didn’t see any more. We saw no lifeboats around us. We saw the lights on the shore.

We struck out for shore. The water was warm. The waves seemed to help us along towards shore. Best of all, we kept side by side all the way. We’d help one another keep afloat now and then, one of us taking it easy for a while. Then we reached the beach. People on shore rushed into the surf to drag us out and they took us to the hospital.

The Cohen’s long swim took over six hours.

Mr. and Mrs. Cohen were well known in Hartford, and their return home drew much attention. Harriet carried with her the child’s lifebelt with which she escaped from the ship (Abraham’s belt, which had been cut off of him, would later be mailed to them from New Jersey) and after attending Rosh Hashanah services at Temple Beth Israel they retired to the home of Harriet’s parents’ where a small group had gathered to give thanks for their rescue. A transcription of an interview they gave soon after follows:

H: I didn’t see any flames along our corridor, but above me and on the other side of the ship I could hear screams.

(The Cohens’ cabin was an outside on C-Deck, just aft of the Purser’s Lobby, on the port side. Leaving Abraham sleeping, Harriet walked astern on B Deck to learn what was wrong. She soon returned to the cabin, wearing a child’s life jacket a man had handed to her.)

H: I returned to our cabin and found my husband dressing and putting on a life preserver. He had one for me, but I kept the one I had on.

A: I went out into the Purser’s Lobby. There were members of the crew in the four corners of it squirting water against the ceiling. There didn’t seem to be much pressure, but if there had been all the pressure in the world it would not have made any difference. I spoke to one of them and he swore.

We found our friends all dressed up as if they were going out shopping.. They were alright, and we left them. The reports say they were saved.

(The shipboard friends were Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Vitale of Detroit, Michigan)

A: Then we went toward the stern of the ship. The corridor was full of people all moving toward the stern. It wasn’t crowded and the fire seemed all above us, on the upper decks. No one jostled or hurried. We went back to the open part of B Deck.

We couldn’t move around. Someone began to sing “Hail Hail the Gang’s All Here” and someone else said they ought to say their prayers. Some woman say, ‘yes, that’s right. Prayers.’

There were two members of the crew huddled with the rest. They were sobbing, with tears streaming down their faces. Everyone was excited, but some big stocky fellow seemed to have them well under control. Then the lights went out. The big fellow said it was all right, that the ship was steel and guaranteed not to sink, that people would get to us right away.

A little while later the fire began to increase.

The smoke began to pour back. People were choking and the women began to scream again. I wet the shoulders of my wife’s gown and buried my face in it. People were crying out that we would suffocate. It couldn’t last long. Some of the passengers tried to go up to A Deck but were apparently warned not to.

People on the inboard edge of the crowd around us were pushing and screaming for those near the rail to jump. They were afraid to, and we who were quite far from the rail were suffocating. I took my wife’s shoulders and pushed her through the crowd until we reached the rail. All we wanted was to get to the water. We both had life belts on. Anything was better than this.

H: We were right in the middle of the stern. I could see the lights on the shore in a low line to my left. Except for those, it was pitch black.

A; I put my arm around Harriet after we climbed over the rail. We said ‘Let’s go’ and jumped. I hit the water flat on my back and it knocked the wind out of me. Harriet hit feet first. When we recovered from the shock, Harriet said ‘The water’s fine!’

There was some sort of light like a tin can with a flare on it that was floating in the water. Some of the people called out to stay near the light. Then a funny thing happened. The lifebelt my wife had tied on me was a little loose and we called out to some people who seemed good natured and went over to them. I turned around and one of them fixed it.

H: The whole ship seemed afire. There was smoke on the water and the waves were high, but it was warm. We were afraid the ship might sink so we moved away from the light on the water. Then we thought the ship might explode, being full of oil, and we swam further away. We had our lifejackets laced up the back and it was easy to swim. After that we never saw another person and we drifted away from the ship.

When it began to be light we could no longer see the lights on shore as the waves lifted us. They must have been turned out, and it began to rain. I never saw such rain. We were never discouraged. We thought that at any moment a boat would come along. When we saw one about an hour alter we thought another would soon be along when they failed to see us. We talked all the time. We worried about the people at home. We could see the smoke from the ship for a long time after we jumped.

A: It was a long time, and it wasn’t pleasant. We swallowed water. I was sick. We began to get cold. It must have been 9 O’clock when we first saw the houses at Point Pleasant. We said ‘Take it easy’ and talked about a lot of things.

H: Sometimes we thought we were getting nearer shore, then we didn’t know. Then we knew we were getting nearer and soon saw a tremendous crowd on the beach. When the waves lifted us on their crests, we waved. Then we were able to see that the people were waving back to us. There were no other swimmers near us. We couldn’t understand why they didn’t come out to get us. The surf must have been too high. The last quarter mile was the worst of the six hours. There was a bathing beach there and some sort of wooden things holding up a barrier. It was about 100 yards from shore. My husband and I were thrown against it. Still no one came out. We were tangled in the ropes. My husband was thrown clear after swinging around them and then someone swam out and got him. Then they got me. He was pretty sick and the men, big ones, I don’t know who they were, were almost tired out with taking us in.

A: It was awful. They told me there were bodies being washed ashore, some of them with their arms charred. These people had been afraid to jump.

There is one thing that was lucky for us, ‘though. The engines of the boat had been stopped when we jumped.

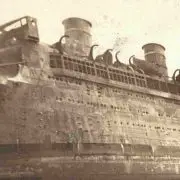

We saw the vessel where she was beached at Asbury Park We couldn’t believe we had ever been on her. It didn’t look like the same boat.

Abraham Cohen was remembered in 1934 as an outstanding athlete from his high school and college years. After being awarded ‘Most Outstanding Athlete’ and ‘Most Outstanding Student’ at Hartford High School he attended the Dean Academy, and later Dartmouth where he played on the championship basketball team two years running and was a member of the varsity football team. At the time of his marriage, he was the manager of the Grand Department Store in Hartford.

Harriet Elsner Bacharach Cohen was salutatorian of her graduating class at Bulkeley High School. She attended Smith College from 1930 through 1932, and then transferred

to the Prince School of Simmons College, from where she graduated in 1933. She served as president of the Temple Beth Israel Junior Congregation, and at the time of her marriage worked in the comptroller’s office of the G. Fox Department Store in Hartford.

1934 articles did not mention it, but Harriet celebrated her 22nd birthday on September 9th, one day after she and Abraham made their six mile swim. The Cohens had two children, and Harriet maintained a busy professional and social life, working as a bank officer at Washington Federal Savings and Loan, and functioning as the president of the Society of Real Estate Appraisers; the president of the Emma Lazarus Chapter of B’nai Brith, and the President of Renanah Chapter of Hadassah. She was also active in South Shore Hospital. Mrs. Cohen died in New York City on November 25, 2002. Abraham predeceased her, dying in West Palm Beach, Florida on May 13, 1988.

The Cohens’ onboard friends, the Vitales both survived. Mrs. Vitale left this brief account of the disaster:

Seven hours we had been in the water. We were bruised, our eyes burned from smoke and salt water. Our flesh was singed and raw from the fire.

I was ready to give up, let go, let the waves take me. My husband said:

“I know how you feel, but if we give up who will take care of Donna Joy.?”

She’s 17 months old, our baby. I couldn’t let go then. So, we locked our hands together and hung on. Dead bodies slapped against us- and floated on. A boy, about 13 years old, drifted up to us and asked if he might hold on to us, too. He was afraid, he said, and lonely. So, three were three of us, hanging together in the sea.

And it couldn’t have been more than an hour after that when a coast guard picked us up, put us on the City of Savannah and we began to live again

Many passengers, seeing no sign of lifeboats or rescue craft set out to swim to shore. Among them were Charles and Selma Filtzer, a honeymoon couple from Queens, New York. Unlike the Cohens, the Filtzers had trouble making their way, and after several hours in the water a large wave submerged the couple. Selma resurfaced and was eventually rescued; Charles was not seen alive again and was identified at a temporary morgue in New Jersey. A 1934 account is worth quoting in full:

Life has not dealt kindly with Mr. and Mrs. Bernard F. Filtzer of 115 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn.

Seven years ago their daughter, Mrs. William F. Yarm died following the birth of her first child. Yesterday, their one remaining child, Charles, 27, was buried in Mt. Hebron Cemetery.

Two weeks ago they saw Charles married to Selma Widder, of Mayfair Road, Kew Garden, Queens. Two Saturdays ago they went to the Morro Castle to wish the young couple Godspeed on their honeymoon.

Yesterday, on the eve of the Jewish New Year, at Kirschenbaum’s Funeral Parlor, Throop Avenue, they stood beside Selma and listened mutely while the widow told how Charles had drowned.

They jumped together from the Morro Castle, Selma said, and swam side by side in the cold sea for six hours. Suddenly a huge wave separated them. Two hours later she was picked up by a rescue boat. Her husband’s body was swept ashore.

The young bride accompanied Charles’ mother and father to the side of the coffin. She touched her husband’s cheek with her hand. Sobbing, the three walked away arms linked, supporting each other in their grief.

Charles, a buyer for the May Company, was a brilliant young businessman and a sterling sportsman. His bride was his first love. He had a happy future ahead of him-but fate ruled otherwise.

Bernard Filtzer, Charles, father survived until early 1936. Ellen, his mother, lived only a year longer dying at age 57 in 1937. Efforts to trace Selma Widder Filtzer have so far been unsuccessful.

Alexander and Freda McArthur of Philadelphia, jumped from the Morro Castle together, and like the Cohens and the Filtzers attempted to swim to shore. Alexander began to weaken after three hours in the water and finally, after saying, “Don’t try to help me, save yourself.” slipped into unconsciousness and then died. Freda continued to swim while carrying her husband’s body. John Bogan, Jr. of the Paramount later told author Hal Burton that Mrs. McArthur had initially refused to abandon her husband and was hauled aboard, weeping, as his corpse floated away:

“We couldn’t waste time with the dead, but it took us at least ten minutes to convince her.”

(Shipwrecked. Hal Burton. Viking press. 1973.)

Alexander washed ashore at Sea Girt later in the day. The 37 year old insurance man left two children, Dora, 15, and Alexander Jr., 5, neither of whom made the voyage.

Mr. and Mrs. Edward Brady of Philadelphia were returning from Havana with their teenage daughter Nancy. The three leapt from the stern together, but Nancy was soon separated from her parents by the waves. Edward Brady had been in poor health and the trip was meant to act as a restorative. The two swam together, but Mr. Brady began to fade as exhaustion set in. He told Mrs. Brady “I am not afraid to die, but I hate to leave you.” and his last words were, reportedly, “I’m going. I can’t keep up.” He then slumped forward, unconscious, and soon died. Mrs. Brady survived, as did Nancy.

Una Cullen, a pretty 21 year old from Queens, was part of a large group of women who swam and drifted most of the way to shore that morning. For two of the group, there was a literal last minute tragedy:

Because it was our last night on the ship, a group of us were staying up very late. I was in the lounge with Mae Maloney and two other shipboard friends. We heard the crew moving about and smelled smoke but did not think much about it, as a steward told us not to be alarmed. He said it was just a small fire and the crew could put it out easily.

Then suddenly a great cloud of smoke came right through the lounge. My room mate, Helen Williams, was in our stateroom, and the life preservers were there, so I ran down. I woke up Helen, put on my coat and a life belt and went back up on deck. By that time some of the crew had lowered a life boat and we were directed to go down a rope ladder. As I was climbing down my heel caught and I fell into the water. I thought that was the end of me.

But, when I came to the surface I saw Mae Maloney and her mother, and another girl Dot Vergenstein floating near me. So we all joined hands in the water and thought we’d stick together. The four of us, still holding hands floated for about seven hours. We didn’t try to swim much, but we were carried towards shore.

Then when shore was only a few hundred yards away, Mrs. Maloney (actually, Mrs. James Dillon of Brooklyn) died as we held her hands. I suppose the shock and exhaustion and immersion were too much for her. It was horrible.

The remaining women drifted in the tidal zone until they were picked up by a small boat and brought ashore alive. Mrs. Emil Lampe, another member of the group, recalled for author Hal Burton in the early 1970s:

We all held hands but pretty soon Mrs. Dillon became delirious. Then she smiled, her head slumped forward, and I could feel that her hands were cold. Mae kept saying ‘I hope mother will wake up’ but I knew she never would. Just the same, I kept hold of one of her hands until a lifeboat picked us up.

(Shipwrecked, Hal Burton, Viking Press, 1973.)

Mae Maloney, a young lady in her early 20s who bore a strong resemblance to Susan Hayward, was hospitalized for shock, and the after effects of immersion, in New Jersey. Photographs of the strikingly beautiful survivor lying in her hospital bed were widely run in the newspapers in the days following the disaster.

53 year old August Sheely, of Glendale, Long Island was taken directly from the Furness-Bermuda Line pier to his Cypress Hills Road home, still in the wet clothing in which he had jumped from the Morro Castle. The father of three was put to bed under his doctor’s orders, suffering from shock and badly bruised legs.

August, and his wife, Frieda, had been awakened by the smoke and noise in the corridor outside of their cabin. They made their way to an upper deck, where they kissed one another before jumping into the sea together. Mr. Sheely told his children that he and Frieda had stayed together in the water. He fell into a stupor, but he recalled being pulled into a lifeboat from the Monarch of Bermuda, and was certain that his wife had been pulled aboard as well. He awaited her return, but Frieda Sheely was never seen alive again; she may have died aboard the Monarch of Bermuda, or may not have been pulled into the lifeboat at all.