Morro Castle, Mohawk and the end of the Ward Line : Part 2

Part two of Jim Kalafus’s epic history of the Morro Castle disaster.

Final Departure

1934 proved to be an uneventful year for the Morro Castle after the turbulent latter half of 1933. Cuba remained unstable, but through September the Morro Castle managed to avoid being drawn into shore based trouble, and if any untoward events took place they did not make the papers.

1934 proved to be an uneventful year for the Morro Castle after the turbulent latter half of 1933. Cuba remained unstable, but through September the Morro Castle managed to avoid being drawn into shore based trouble, and if any untoward events took place they did not make the papers.

In June she was chartered for a second time by the Philco Radio Corporation to serve as a floating convention center, and to judge by the name count on surviving passenger lists, business was normal throughout the summer. People who had been in Havana in the months before the Morro Castle was destroyed would later tell author Hal Burton that it was hardly a tranquil vacation spot, but the Ward Line ships were once again fostering the illusion of safety and most passengers came away from their vacations favorably impressed.

A complete scrapbook from the ship’s second to final round trip survives, in which was preserved virtually every piece of paper accumulated during the seven day voyage. After reading it, one gains insight into how the Ward Line managed to put a favorable face on a city, and a country, in the grip of a revolution: passengers were kept moving at a brisk clip through selected parts of the city, visited sites that were pretty or frivolous, and were given almost no free time in which to roam. They came away from the city having seen Havana without actually seeing it. One of the few passengers who did venture off on his own before the fatal voyage later recalled being arrested for violating curfew, and being able to escape back to the ship by walking out of custody when a bomb detonated next door to the police station. Most people, however, viewed the beautiful beaches, public parks and mansions of the “better quarters” of Havana from inside one of the Ward Line- provided busses or limousines; drank ‘exotic’ mixed drinks at one of a series of Line-sanctioned bars; danced to Cuban music at an open air nightclub, and probably returned to the US under the impression that the stories about the turmoil of the previous year and its ongoing repercussions were exaggerated.

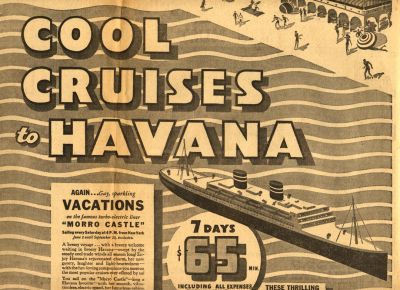

Advertisement for Morro Castle’s Final Voyage

When the Morro Castle departed Havana for the final time on September 5th 1934, she carried aboard her 318 passengers and a crew of 231. Her complement was typical of what could be expected on the final late summer voyage before the opening of schools and the start of hurricane season. There were a number of students who had spent the summer in Mexico and Havana returning to their respective high schools, preparatory academies and colleges. Just short of a dozen doctors and their families were aboard, as were a priest and a minister. A former Yale tennis star and his family sailed, as did a former Dartmouth football team member and his new wife. The large- and entirely doomed- family of a Cuban doctor who resided in both Havana and the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in NYC settled into a pair of boat deck cabins, and a Brooklyn dentist and his grammar-school age son, aboard to discuss the doctor’s impending remarriage in a pleasant environment settled into their less lavish rooms aft on D Deck. There were bank presidents and bank secretaries; an orchestra leader turned architect turned insurance salesman and his family; police officers, and a former child actress turned model and her new husband. More than 100 who boarded were members of the Concordia Society, a German singing club with membership from Brooklyn and Queens. Below decks, there was a steward anxious to return to New York City where his wife was due to give birth the day the ship arrived, and a printer worried for the safety of his stepson- a crewman also- who had been carried off the ship seriously ill in Havana and hospitalized. There was a Columbia University dropout working as an oiler, and a musician making his final voyage before starting a shore based job. Perhaps best known before the fire was the “Millionaire Stewardess” Sarah Kirby who had been the subject of many a human interest story after it was discovered that the elderly woman had parlayed a small inheritance into a relative fortune (one suspects, however, that the million dollar figure was an exaggeration) but kept working because she loved her job.

Passengers on deck during a Morro Castle Cruise

On September 7th, as the voyage drew near to its conclusion, the series of events that culminated in disaster commenced. Captain Wilmott, who had been – anecdotally – described as “not himself” was found dead in his bathroom at the start of the final Gala Evening at sea. Stories of poisoning and intrigue later circulated, but Wilmott’s final recorded words (‘could you mix me up an enema?’ delivered by telephone) and the fact that he was found toppled over into his bathtub with his pants around his ankles strongly suggest that he died of a heart attack or a stroke while trying to force a bowel movement; the doctors who were summoned agreed that it most likely was a heart attack. That night, as the new chain of command was being established and the weather deteriorated a fire was discovered in a storage locker in the port side B deck Writing Room. The ship was kept sailing into the wind for a regrettably long time, driving the fire aft, up through the lounge well, and out onto the boat deck. Passengers, unable or unwilling to risk running through the flames to reach the boats congregated on the open decks aft on B, C and D Deck. The vast majority of those who escaped in the Morro Castle lifeboats were crew members, a fact later to draw much negative criticism, mitigated somewhat by the fact that they were quartered forward on the ship and had a knowledge of onboard shortcuts and crew staircases that the passengers did not possess. Those trapped at the stern began jumping when it appeared that the flames were about to burst from the superstructure on to the aft decks. Many broke their necks or knocked themselves out jumping improperly with life preservers on, while others jumped or were thrown from the ship without any life saving devices only to weaken and drown struggling in the increasing storm.

Passengers who did not awaken in time had to jump from the cabins in which they found themselves trapped by the fire. Few survived – crew members on the bow spoke of how the passengers were coming out of their portholes head first and knocking themselves out as they somersaulted towards the water and struck their heads against the side of the ship, or landed on their stomachs hard enough to stun themselves and then drifted astern face down in the water. Those who stayed with the ship until after daybreak had a high survival rate- rescue ships had arrived on the scene and those who remained went overboard to cling to the ropes which hung from the liner’s side until help arrived. Those who jumped during the first hours, before sunrise, had mixed prospects. Some formed large groups in the water and supported one another until rescue came. Others struck out for the clearly visible shore and a surprising number of those survived the six mile swim. However, many who drifted alone or in small groups died of exhaustion and exposure waiting for the rescue vessels that had too little time to search too large an area for survivors.