The Lusitania : Part 9 : Earlier Voyages

Lusitania, Eluding Enemy Nears Port…

The general perception of the events leading up to May 7, 1915 is of a relatively normal service life suddenly disrupted by the famous German newspaper warning, after which came the disaster. Some authors make reference to the famous incident in which the Lusitania ran up an American flag for protection in the war zone around Britain but, for the most part, little is ever reported of the ship’s life during wartime. The warning of May 1st. marked another step in an increasingly tense phase of the Lusitania’s life, for the previous voyages had been anything but tranquil. A few excellent accounts have survived; detailing what life was like aboard the lost liner during her final ten months:

Lusitania, Eluding Enemy Nears Port:

August 8: After a dash across the ocean, during which she eluded the German cruiser Dresden, the Cunard liner Lusitania is expected to arrive here tomorrow unless she meets some mishap on the last stage of her voyage.

Wireless messages from the Lusitania state that she is making excellent time. She steered southward out of her regular course after being warned by the British cruiser Essex that the Dresden was waiting in the regular lane to intercept her.

Among the best narratives from this period is an August 12, 1914 account by passenger Herbert Corey who beautifully captured the tension of an early wartime crossing:

Eight days out from New York, the crippled Lusitania anchored in the pool of the Mersey. A naval officer climbed aboard her bridge and, after formally taking possession in the name of the government, began a supper party which lasted until 2:30 o’clock in the morning. The purser began doing thriving business, exchanging seventy-five cents in British money for each good American dollar offered. These were the crowning sensations of a passage filled with thrills- and gossip- most of the thrills being traceable to twittering nerves.

The events of the voyage may be epitomized as follows:

Ten minutes away from the dock in New York, the low pressure turbine went to smash. Obviously it had been tampered with by some emissary of Germany while the boat lay at the pier.

Fifty miles off the coast of America, she was chased by a destroyer of some sort. Captain Dow said she was a German destroyer. Everyone worried busily. By and by the destroyer was dropped by a steamer which could steam a scant nineteen knots in her one-legged form.

The wireless news went perfectly crazy. We heard of a naval battle in the North Sea in which nineteen German ships and six British vessels went to the bottom. Captain Dow sent up a rocket from the bridge. In the midst of his gratulation he sounded a note of grief:

“Poor O’Callahan” he mourned. “He went to the bottom in his flagship, the Iron Duke.”

Next day it developed that there had been no battle, no lost Iron Duke, no martyr O’Callahan. Therefore, the morning paper, which might have contained this cheering information did not appear. The ninety-eight first class passengers, a lesser number of second cabin men and women, and a hundred-odd in the steerage were left to play with their fears and surmises.

Upon the authority of the bridge the statement was made that some seafaring liar in New York had reported the Lusitania blown up and sunk with all hands. This was disquieting, to say the least. Not a man or woman on board but had friends in New York- and in London, where, according to bridge authority, the story had been reprinted- to which this fake meant the bitterness of death. But the use of the wireless was not permitted.

“We are under war orders.” announced the bridge. “Not a word may be sent by wireless.”

At night the steamer crept along without a light showing. Even her green and red lights were off duty. Her windows were curtained. Her interior halls were dark. One groped to find one’s stateroom at night through gloomy passageways, colliding with shuddering stewards who spoke in whispers.

It was weird, an unusual experience. People who owned sensibilities began to feel them jerking. It brought home to them the fact that war is actually upon the seas- that after half a century of peace the privateer may again be regarded as a possibility, and that innocent people are exposed to the danger of capture as prisoners of war.

“Suppose we are captured?” asked Guy Standling, the actor, of the British consul in New York, previous to embarking upon the Lusitania.“In that event, what will be my status as a British non-combatant?”

“Undoubtedly,” said the consul, “you will be exchanged- ultimately.”

It was 1:15 in the morning when the Lusitania backed away from her pier in New York. To do so, steam was turned into the low-pressure turbine, which is used for reversing the propeller.

“Whang!” went the engine.

There can be no doubt that it had been tampered with while the steamer lay at the pier. A screw the size of a five-cent piece once before played hob with this delicate engine. Someone had monkeyed with the steam ports this time. The evident plan was not to prevent the Lusitania from sailing, but to cripple her that she would prove easy prey for a faster vessel that might be lying in wait.

That faster vessel- according to Captain Dow- was laying in wait. We were fifty miles off the coast and 159 miles from New York when she was sighted on Wednesday morning. Fortunately, she was at a distance estimated at six miles.

“I can only say that she was a destroyer, burning oil and that she chased us” said the officer on watch at the time. “She did not run up a signal flag giving her nationality. She merely signaled to us ‘You are captured. Heave to!’ “

But we didn’t heave to. Instead we ran as hard as a cripple chasing a pig. The sea was a bit tumbled, and in a minute a wraith of fog crept over the sea, shutting off a view of the presumed enemy. When it lifted, she was out of sight. Captain Dow had shifted his course, and eluded her.

That was the last of real happenings. We passed into the realm of the unreal. The moment that wireless news began to come in, we were treated to the wildest feats of surmise treated as fact the imagination can conceive. A battle was reported in which 30,000 Germans were killed- no wounded being reported- while 15,000 brave Frenchmen laid down their lives. Alsace and Lorraine had been regained. The Teuton hordes were in full retreat. England had sent an immense army to Belgium.

“If this is true” asked Frederick Roy Martin, manager of the Associated Press at New York, ”let me get in touch with my office. I can get the exact truth for you at once.”

“We are not permitted to use the wireless” was the reply. “We can receive but not send.”

And so we sauntered along on the slowest voyage the Lusitania has ever made- her log shows it- talking, worrying, whispering, lights out, dodging every time a fishing smack’s sail showed on the horizon, as nervous as a boarding school girl at her first party. In the safe of the vessel was $6,000,000.00 in gold (Note: That sum is vouched for by gossip only; no officer would confirm it!) not to speak of thousands of dollars carried by individuals.

The Lusitania was under government orders from the moment she passed Sandy Hook. In the Mersey she was formally taken over. Her anchor was dropped about ten o’clock on the night of August 11. A naval officer climbed to the bridge.

“When can we go ashore?” the passengers asked the purser.

“I don’t know.” said that official, yawning.

“When will we land?”

“I don’t know.”

And he didn’t care to know, apparently. Neither did any of his force. The ship was in the service of the government. This is a state of war. The passengers and crew alike would be disposed of when the admiralty wished. There was no more to be said.

Later on the reason developed. All the buoys in the Mersey have been lifted. There was a fog on the water. It was not possible to take so large a vessel to her landing place in absolute safety. It was possible to send a tender out to her- two tenders were tied to her for hours- but no one was permitted to go ashore. Why? War!

Ashore the wildest rumors were in circulation, and came to us by pilot. Liverpool was under martial law. All Germans had been ordered to report once a day or be shot as spies. One German had been shot. Our German- a most inoffensive passenger- had been made prisoner of war. He would be handcuffed when we landed. Passengers were cautioned- by each other- not to speak German. That way danger lay. The broad port of the Mersey, usually bristling with shipping, seemed deserted under the foggy sun.

One began to sense the fact that a great war- a world war- is actually in progress.

A few days after the disaster, William Foulke, of Richmond, Indiana, composed this account of a crossing he made aboard the Lusitania. The voyage, which began September 12th, was the first she had made since the incidents related above:

The Lusitania was one of the fastest passenger ships afloat, and was the most beautifully furnished I ever saw. The rooms on the deck were like clubrooms.

The boat was painted gray for the voyage we took last fall, so as to be as inconspicuous as possible, but the captain did not order the cabin lights extinguished at night. We were subject then to possible capture by German boats, but none on the ship seemed to be afraid of that. The thought of submarines never entered our minds, as the submarine phase of the war had not developed at that time.

I was greatly surprised to learn the ship had been torpedoed. It was faster than any submarine, so it could not be run down. It looks to me as though the captain would have to have the ship shift its course continually after getting into the English Channel and the Irish Sea, so the submarines would not have known where to strike.

The ship could have gone around to the north of Ireland and down from there to Liverpool and thus it would have been less liable to destruction. The boat made the trip to New York last September in five days.

The Lusitania Commandeered as Transport.

She is to go to Halifax.

And There, the Report Declares, Take on Canadian Troops for Europe.

September 18: The Cunard Liner Lusitania, from Liverpool, reached her pier here early today under wireless orders received last night as she was nearing port, according to passengers, ordering her to make all possible speed, unload her passengers, and be ready to sail for Halifax to act as a transport for Canadian troops. The officers would not verify this report, but offered no explanation for rushing the big liner to her pier at one o’clock in the morning.

Prominent among the 1502 passengers, the majority of whom were returning Americans, were Sir James Barrie, author and playwright; A.E. Mason the English novelist; Mrs. George Vanderbilt and Miss Cornelia Vanderbilt; George deForest Lord; Marshall Field III; Chauncey Depew, Jr. and William Dudley Foulkes, president of the Municipal League of the United States.

Also on board was Ralph Moodie of Gainesville Texas, who would die on May 7, 1915. This particular celebrity-laden crossing would later feature in just about the only positive publicity the liner garnered during her final nine months:

February 1915:

The Sensible Romance of Marshall Field III “The Richest Boy in the World”

How the Future Heir of $200,000,000.00 American Dollars Turned His Back on Every Proud and Titled Foreign Beauty…and Picked Out for His Bride A Simple, Charming American Girl.

…from all accounts his engagement to Miss Marshall was the result of a brief but pretty romance aboard the ocean liner Lusitania, aboard which they were recently fellow passengers from Europe. There are stories of smooth walks on the promenade deck lasting until the early hours of the next day. It was remarked by passengers that the young man seemed deeply smitten.

Those interested passengers had their reward a day or two before the Lusitania reached the port of New York. For some time the young man had not been in evidence. Suddenly he appeared on deck- alone, but looking very happy, quite the expression of a sighing lover who had staked his future happiness on a certain answer to a certain question and had not been disappointed.

Marshall Field III, with his retinue of servants, put up at the Ritz-Carlton. Miss Marshall went directly to her home at 6 East 77th street, where young Field was observed as a frequent caller. And presently came the announcement of their engagement.

Other articles spoke of the smitten couple keeping constant company in the lounge, dining room, verandah café, and on the boat deck. Journalists, and friends of the couple, enjoyed playing up the Lusitania angle when they married in February 1915. This was the last touch of romance to attach itself to the liner. Marshall Field III and Evelyn Field remained married for about fifteen years; upon their divorce she was awarded S1, 000,000.00 per year in alimony and their New York residence.

Lusitania Sails

October 3: The Lusitania sailed today with a large compliment of notables including Assistant Secretary of War Breckinridge, and the army officers who came over on the U.S.S. Tennessee.

Everyone is glad to be on the way to the land of the free, where daily baseball scores promise much more exciting reading than the dribbles of censored war news printed here.

Miss Sarah Cooper Hewitt and her sister, Miss Eleanor Cooper Hewitt, were aboard the Lusitania; returned recently from Italy.

Jerome K. Jerome, the novelist, lingered in a corner of his room and refused to talk about a new play which he is going to launch.

Bishop Rhinelander, of Pennsylvania is also hurrying home. Other notables on board the Lusitania include Miss Elizabeth Frick; Mrs. S.R. Guggenheim and family; Mrs. P.H. Mellon and daughters; Mrs. Frederick Orr-Lewis; Mrs. V. Henry Rothschild and Mrs. Gertrude Cornwallis West, better known as Mrs. Patrick Campbell, the actress.

Aboard this voyage were at least five passengers who would be on the May 1, 1915 passenger list. Thomas Slidell and Frederich Schwarte would survive, while Walter McLean; Lee Schwabacher, andHenry B. Sonneborn would not.

War Zone Gadabout

A brief account of the Lusitania’s next eastbound crossing appears in Walter Austin’s 1917 book A War Zone Gadabout:

FLIGHT THE FIRST October 14 — December 16, 1914

It all started back in 1898, when I tried to get into the Massachusetts militia so that I could go to Cuba and fight Spaniards. Being refused, I got a billet as supercargo on a supply ship and sailed into Santiago in time to see some of the “doings” — just enough to whet my curiosity and my taste for adventure. Then in 1904-1905, during the Japanese-Russian war, I happened to be in Japan. Here was another — and a bigger — chance, I thought, to taste adventure and to see history in the making, but a cold “turn-down” by the Mikado’s government kept me from steaming away on a self-commandeered craft to the siege of Port Arthur.

In the fall of 1914, however, I had better luck, for on October I4th I sailed from New York on the Lusitania for Liverpool. I must confess that I had no better excuse for going abroad than sightseeing, but that seemed to me reason enough. The first general European war in ninety-nine years had burst upon an unsuspecting world, and I wanted to have a glimpse of those conditions that had long been talked of as possible, but that few, if any, Americans had expected would come in their day. Besides, I had wagered a box of cigars with a friend of mine that I could get to England, Germany, Belgium and France and return to New York before Christmas. Hence my determination to smell the smoke of Battle in order to puff the cheroot of Peace.

We had a very smooth passage and sighted but one vessel during the entire trip. The steamer’s transformation gave us our first intimation of warfare. It was painted gray throughout, and at night all lights were carefully covered. When we arrived off the Welsh coast at night we had a sterner omen of strife, for searchlights from the shore were constantly played on us. But there was no apparent anxiety among the passengers, since that was before the days of submarine ” frightfulness,” and we docked safely.

From Liverpool I proceeded at once to London, where I put up at Morley’s Hotel in Trafalgar Square — that quaint tavern of uncertain age and indubitable British atmosphere. The next day was Trafalgar Day. About the Nelson Monument, in front of the hotel, was gathered the largest crowd I had ever seen. At the base of the shaft were strewn wreaths, contributed by veterans of many wars, from the Crimean down to the present conflict. Among the most touching were those sent by the survivors of the Aboukir, Cressy and Hague, the British cruisers which not long before had been sunk in the North Sea by the German submarine, U-5, with a loss of 1,500 men.

Lusitania Not Heard From

October 30: The Cunard Liner Lusitania, which left Liverpool last Saturday, has not been heard from since. She was due off Ambrose Channel light ship last night, and should have been at her dock by 6 o’clock this morning. At the offices of the Cunard Line here, it was said that the Lusitania had probably been forced to reduce her speed because of a gale blowing off the coast. The Cunard officials said that they expected the steamship to report during the afternoon.

Lusitania Arrives

October 31: Anxiety regarding the Cunard liner Lusitania, which had not been heard from since she left Liverpool Saturday with 961 until she reported her position by wireless last night, was relieved when she arrived here today more than 24 hours overdue. The weather was responsible for her delay.

On board the Lusitania on this trip were Josephine Burnside, who would survive the sinking, and her daughter, Iris, and maid, Mattie Waites, who both be lost.

Lusitania is Rigidly Guarded Against Bombs

December 5: Precautions against bombs, so rigid as to be almost without precedent in this port, were exercised today by Cunard Line officials upon the sailing of the steamer Lusitania for Liverpool. She carried 1,190 passengers. All of those who were unknown personally to the officials were stopped before boarding the vessel and made to prove their identity before they were allowed to proceed.

The Lusitania carried 9000 sacks of Christmas mail.

David Samoilescue, actor, was returning to his Charing Cross Road residence in London on this crossing, after spending a month in New York City visiting with his wife and children. He would die aboard the Lusitania five months later.

January 1915 westbound crossing…

The Lusitania’s January 1915 westbound crossing saw amongst the passengers actor Maurice Costello (great-grandfather of Drew Barrymore); poet Alfred Noyes, and at least six people who would be aboard the final crossing: Julian de Ayala; Robert Wishert Cairns; Edgar Gorer; Gerald Letts; Frank Partridge and Martin Van Straaten. Gorer, Letts, and Van Straaten would die.

Final arrival in New York

The February eastbound voyage became the most infamous completed voyage of the Lusitania’s career.

Californian author Will Irwin left an account which excellently captured the social side of the voyage,as well as the undercurrents of intrigue aboard the liner and an oblique reference to the son-tro-be-notorious international incident:

On Board the Lusitania.

…the “state of war” begins, in fact, at the pier. This was no common sailing of an Atlantic liner, anyone could see that with half an eye. There was much excitement in the crowd which came to bid us goodbye, much emotion expressed and suppressed. Wives clung emotionally to their husbands; a few women, blinded by their tears, refused to wait to see us off, but ran away down the pier before the deckhands drew up the gangplank.

When, finally, the shores of America faded away in the mist, we came across our first sign of real war– the British cruisers which for four months have stood at anchor just outside the neutral zone, monotonously waiting for something to happen. We always bestow a little sympathy, in passing, on the crew of the Essex.

…the war is settling down to its pace, the “piker” sail the sea no more. This is a passenger list of old, experienced voyagers. It had been a rough passage– no worse, probably, than any other February passage, but no winter trip on the Atlantic is very comfortable. Besides, the Lusitania is loaded with certain mysterious and very heavy contraptions of steel she was not meant to carry, and she rolled miserably in the winter gale.

Nevertheless, the dining-saloon and the smoking-rooms have been almost as well filled in the rough days as in the smooth. These are people who got over the habit of seasickness long ago. There is the regular delegation of American buyers, over to get the advance spring styles from Paris. Most of them will not cross the Channel this season; the Parisian dressmakers will move their stocks over to London and meet them halfway. There are at least a dozen gentlemen, American and foreign, concerned in supplying the allies with munitions and clothing. There is a delegation of young and adventurous Americans billeted to our hospital at Paris: they are going to drive motor ambulances from the front to the base hospitals.

There is Mary Garden, going over to be a nurse. Elsie Janis, Joe Coyne and Frank Belcher are going to fill theatrical engagements just as though there were no war in England. Ernest Thompson Seton is on a lecture tour. He had supposed that his winter engagement was off, until he communicated with his manager in London. They spurned the idea that Great Britain was letting the war interfere with anything.

Ex-Senator Lafe Young, of the Des Moines Capital, is going over at age 66 to be his own war correspondent. The other newspapermen aboard tell him that this business of sending cub reporters to a great war has got to stop. George Doran, the publisher, is on his way to see why British authors are not writing. Mark Sullivan, editor of Collier’s is trying to inform himself first hand on the European situation. George Tyler will look over the theatrical situation. Dr. Crozier, of Winnipeg, veteran of the Boer War, finding himself too old for any more fighting, will go to the front as an army surgeon. W.D. Boyce, the Chicago newspaper publisher, is on his way to Petrograd, not so much because he wants to write about the war, as because he cannot stay away from trouble.

Senator Young remarked yesterday in the presence of Captain Dow, skipper of the Lusitania:

“It would be fun to make every one on board tell why he is going to Europe.”

“Hm” said Capt. Dow, “I’m thinking you’d get some long passages of silence.”

For we have a few mysterious passengers, who seek no smoking-room acquaintances and try to make themselves as inconspicuous as possible. I cannot repeat some of the things I have heard, but there are two or three very pretty little spy games going on under the surface of life on the Lusitania…

…I suspect that as soon as we land in Liverpool, two or three of our passengers will disappear, not to be seen again until the war is over…

We have been going through the motions of a regular voyage on a regular floating hotel; but we have little heart for the game. The auction pool was a failure; the smoking-room gave it upon the fourth night. But the ship’s concert became a live issue. The men who went down on the Cressy, the Aboukir and the Hogue were naval reservists, and as such came under the benefits of the Seaman’s Fund. The mariners of England must take care of their widows and orphans. Joe Coyne and Frank Belcher started to make this the greatest concert ever held on the high seas. Fate counted them out, however. The cold sea air gave Coyne neuralgia, and Belcher, on the night of the biggest gale, was pitched from his berth and strained his ankle. However, Seton-Thompson, introduced by Senator Young as the greatest animal authority since Noah, impersonated the beasts of the forest, Elsie Janis imitated stage people until she wore out her voice, and an English conjurer favored. The collectors got almost one hundred pounds.

Now we are rolling along the milky waves of the Irish Channel. These seas, in peace time so busy and frequented by crafts of all classes, are now as barren and deserted as the open Atlantic. Since we passed daunt Rock this morning we have sighted only one sail. We shall anchor in the Mersey tonight. Tomorrow morning, escorted by a guide cruiser, we shall zig-zag through the mine fields into port. Before that, the British authorities will have put us under formal arrest, that they may search the more readily for spies and secret agents. And the least imaginative among us will realize that we are entering a world at war.

Later: Now this, at the very threshold of war, illustrates the mystery which surrounds all things European in these days; perhaps it illustrates what a world of rumor this has become. This morning, just off the Irish headlands, we slacked up and hove to. The wireless crackled busily for a few minutes, the sailors made some changes in our appearance, which I shall not mention for fear of the censors, then we proceeded again. At 10 o’clock, the regular wireless news appeared on the bulletin board. It consisted merely of the official communiqués. A little later, however, the rumor grew that ten British merchantmen were torpedoed yesterday by submarines in the English Channel. The stewards, when they talk at all, maintain stoutly that it is true. The officers just as stoutly deny it. We shall not know until the pilot brings the newspapers.

LUSITANIA CROSSES IRISH SEA UNDER AMERICAN FLAG TO ESCAPE GERMAN ATTACK

Will Probably Evoke Protest from the U.S.

February 6, 1915: The Cunard Line steamer Lusitania crossed the Irish Sea flying the American flag. The Lusitania sailed from New York January 30, arriving in Liverpool Saturday.

An American passenger said the captain claimed the right to fly the American flag because he had neutral mails and neutral passengers aboard.

While the British Foreign Office will make no formal statement regarding the action of the Lusitania until the matter is presented in definite form, a prominent British official today said that inasmuch as the British government grants ships of other nations the privilege of using the Union Jack to escape capture, it naturally feels that a similar privilege would be granted its ships in a similar emergency.

The British Merchant Shipping Act of 1894 contains the following paragraph:

If a person uses the British flag and assumes the British national character on board a ship owned in whole or in part by persons unqualified to own a British ship, for the purpose of making the ship appear to be British, the ship shall be subject for forfeiture under this act unless the assumption has been made for the purpose of escaping capture.

Parley Likely to Result

Officials read with interest unofficial reports that the British ship Lusitania had entered Liverpool flying an American flag, and it was considered probable that the entire subject of the use of neutral flags by belligerent merchantmen might be discussed in diplomatic channels with both Germany and Great Britain as the result of the charge made by Germany that a British order was in existence permitting such changes of flag.

Two notes, both in the nature of protests against Germany and Great Britain, were slated today to go forth at an early moment from this government according to official hints this forenoon.

While refusing to forecast absolutely their course on the proposed German establishment of war zones around England, officials suggested that they were not entirely satisfied with Germany’s explanatory message, as published from Berlin. Some flatly declared they did not feel that American vessels shall be endangered through misuse of the American flag by Great Britain.

Confronted by this double problem, the state department was understood to be planning a request that Germany give positive guarantees of protection to American ships in the war zone. At the same time, a protest against the British use of the American flag on the Lusitania and its alleged use on other British vessels was scheduled to produce objections from this government.

International law experts felt today that while England in some circumstances might fly the stars and stripes without violating the nation’s honor, her use of the flag at this time distinctly and directly jeopardizes American commerce and American lives. Hence, they believed there is ground for vigorous protest.

Great Britain probably will be asked within a days to furnish the United States with the facts in connection with the hoisting of the American flag on the Lusitania. This was indicated by Chairman Stone of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. The senator held a conference with President Wilson and although he denied they discussed the flag situation, he expressed the personal view that the use of the stars and stripes on the Lusitania was improper.

Passengers aboard this notorious crossing included future Lusitania victims Caroline Hickson Kennedy; Francis Kellett; Allan Loney and Max Schwarz; singer Elsie Janis, who traveled with her mother, chauffeur and two maids; Californian author and journalist Will Irwin; President Wilson’s advisor Colonel E.M. House, who traveled with his wife and her maid; Miss Nona McAdoo, whose father was Secretary of the United States Treasury and whose stepmother was President Wilson’s daughter, Eleanor; and Arthur Courtland Luck, whose wife, Charlotte and sons Kenneth and Eldridge would all die on May 7th.

Ships Sail in Fear of Torpedo:

Lusitania and St. Paul Sailing From England Today.

February 13- Probably not since the early days of ocean travel has there been such nation wide interest displayed in anything marine as that which marked today’s sailings from Liverpool. It was realized there was a possibility of a German submarine attempt.

The Lusitania and St. Paul had their cabins filled. Many Americans have started home, fearing real submarine operations by Germany. Most of them were confident that the Lusitania would not be interfered with on her present voyage.

The new cargo steamer Torquay, of Dartmouth, was docked at Scarborough after being torpedoed eight miles off Scarborough Head yesterday and badly damaged. The steamers Oriole and London Trader are missing and probably sunk.

Lusitania Kept British Flag Up

February 20, 1915

The British liner Lusitania reached New York today from Liverpool having made the run, her officers said, without finding it necessary to hoist the United States flag. On the outward voyage the liner sailed under the stars and stripes while in the Irish Sea.

Fear of the German submarines kept the big vessel at anchor in the Mersey for nearly five hours after she left her dock until an hour or more after nightfall, according to the passengers. The ship’s officers said they were waiting for a favorable tide. The wait lasted from 2:58 o’clock in the afternoon till 7:47 o’clock in the evening. Then the Lusitania proceeded at full speed down the channel in the darkness.

Rough weather prevailed during the entire voyage across the Atlantic and the vessel averaged only a little over twenty knots.

Once clear of the Mersey, the Lusitania did not stop until she reached New York, but carried her Liverpool pilot, James Durant, across the Atlantic and landed him here. He probably will return on the same ship. According to Captain Dow, rough weather prevented the pilot from leaving the ship.

Aboard this particularly stressful sailing ~ unsupported newspaper articles claim that two submarines were spotted tailing the ship ~ were quite a few passengers who would board again on May 1st. Among them were Josephine Brandell; William Broderick-Cloethe; Carlton Brodrick; Joseph Friedenstein; Phyllis Hutchinson; Father Basil Maturin; Maurice Medbury; Arthur Jackson Mitchell; Frederic Orr-Lewis; Frederick Perry;

Anne Shymer and George Slingsby. Miss Brandell; Mr Jackson; Mr Orr- Lewis; Mr. Perry and Mr. Slingsby would survive. A second account of that voyage follows:

Butte Man Tells About the Lusitania’s Race

How the Lusitania raced through the Irish Sea with her body and funnels painted black and with the American flag ready to be hoisted for protection in the event German submarines were sighted is told of by Nils Crook of Butte, a nephew of Otto Olson, a musician and mining man remembered by many old timers.

The Captain of the vessel, said Crook, was opposed at that time to hoisting the American flag.

In Liverpool he was told that the Germans intended to get the big liner, and many reservations were canceled at the last moment. The passengers were advised to be on deck when going through the Irish Sea or at least be prepared for an emergency.

“During the 12 hour dash through the Irish Sea the Lusitania did not show a light although the night was dark“. Crook said. “The great ship trembled from the maximum speed obtained. When the gangplank had been pulled up at Liverpool, the painters made the vessel black, even to the funnels. The ship never stopped to discharge the pilot, and during the night no passengers slept and many sat up in a hysterical mood, as there had been so much talk that the Germans wanted to get the biggest English liner that we were afraid they would do so. Every stoker worked all night, and at daybreak we slowed down and sighted a British man-of-war, but no Germans. The cruiser followed us across the ocean.”

“The owners of the vessel on that trip seemed to feel she might be torpedoed, as the second class fare was raised from $75 to $125. Every one who had the money took out insurance before leaving Liverpool.”

Lusitania Safe in England After a Run In Darkness

March 6, 1915

Moving through the mist in total darkness, the big liner Lusitania, from New York, entered port today, extraordinary precautions having been taken to guard against German submarines. The Lusitania brought 475 passengers, of whom 125 were in the first cabin.

Passing through the Irish Sea last night, all lights were ordered extinguished, and cabin lights were kept burning only half an hour to permit passengers to make ready to retire. These added precautions aroused considerable anxiety among her passengers, particularly because it was reported that German submarine commanders were on alert to attack the big Cunarder.

Captain Paddy Dow, who on the Lusitania’s last trip from New York flew the American flag as he approached Liverpool, denied that he had resorted to such a subterfuge on this voyage. “But I had my locker jammed with flags” he grinned. “If it had been necessary, I would have ran up anything from a harp to the stars and stripes.”

The Lusitania’s March 1915 westbound crossing was notable for the fact that Captain Dow had been replaced by Captain Turner, and for the very large number of May 1st passengers aboard.William McMillan Adams, James Baker, James J. Battersby, Albert Jackson Byington, Isaac Lehmann, George Mosley, Angela Pappadopoulo, Wallace B. Phillips and Frederick Tootal survived, while Henry Agustine Bruno, Alexander Campbell, George Maurice, Frank Gustavus Naumann, Michael Pappadopoulo, Frederick Stark Pearson, Mabel Pearson, and David Walker, F.S. Pearson’s secretary, were lost.

Wallace Phillips

The Lusitania’s final completed eastbound voyage, April 3, 1915, began inauspiciously with a late-season blizzard all but closing New York harbor and delaying the liner’s departure:

Snow Storm Halts Liner Lusitania

April 3: The liner Lusitania, due to sail at 10 o’clock today for Liverpool was held up at her dock by thick weather and a heavy snow storm through which objects 300 yards away could not be seen. With all passengers, cargo and baggage aboard, the vessel lay at her dock awaiting abatement of the storm. Her officers said she would be held so long as the storm lasted- ‘til tomorrow if necessary. Aboard the Lusitania are 833 passengers, the largest list since the war began.

Unusual precautions, even for wartime, were taken to keep from the passenger list any persons whose presence on board was not thought to be desirable. Every passenger had to establish his identity to the satisfaction of the liner’s officers, and no baggage was placed aboard which was not vouched for personally by those permitted to sail.

No Fear

Notwithstanding the dangers of the submarine war zone around the British Isles, the Cunard Line steamship Lusitania sailed today for Liverpool with an unusually large passenger list. Among them were Richard Croker and his bride, and Mme. Leila Vandervlede, wife of the Belgian Minister of State, who has collected nearly $300,000 here for the relief of Belgium.

Captain Turner expected that two fast British destroyers would meet the Lusitania near the Irish coast and convoy the steamship to Liverpool where she is due to arrive on Friday. Care has been taken that no suspected person should be allowed on board, and it was stated that a sharp outlook would be kept for submarines when the steamer approached the British coast.

Chicago journalist Charles Edward Russell, the noted father of mudraking, traveled to Europe in the spring of 1915, hoping to publish a series of war notes compiled during his journey. His first letter, syndicated on April 18, 1915, described his experiences aboard the Lusitania during her previous eastbound crossing. Portions of it chillingly foretell events three weeks in the future.

HOW IT FEELS TO CROSS BY SUBMARINE

Gooseflesh and Nerves Aboard the Liner Lusitania

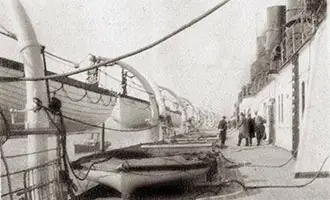

Everybody watched the sailors. They are getting every lifeboat out of its bed and swinging it outboard all ready to launch. This looks like business: ordinarily the lifeboats rest on their beds from port to port and year to year.

Next, the stewards tack black paper over the windows, pull the shutters over the stateroom ports, screw down the deadeyes, blanket the sides in canvas and put out all the deck lights.

This is the most shivery of all; you put your head out of the cabin door and seem to be stepping in to a bale of black wool.

After these precautions, the careful male passenger takes down the life preserver from the top shelf of the closet and drills himself, and his womenkind if such there be, in its use.

Passengers are told if they go to bed that night, to have the life preserver and warm clothing handy. Open boats at night are colder than Greenland’s icy. Some of us improve on this sound advise by putting on the warm clothing, and the life preserver over that, and sitting up all night.

I may observe here that at this stage of the voyage nobody talks about submarines, battleships nor sunken vessels. By some secret psychology the whole subject is dropped. Also we bear ourselves with an elaborate unconcern. But one thing betrays us. At dinner there is some crash of machinery somewhere below, and half the company jump up breathless. Tension–we all feel it.

When we are shot fairly into the danger zone, 300 pairs of eyes sweep incessantly that dull gray stretch of water. No periscope the size of a man’s hand could escape that scrutiny of the volunteer guard. The loom of a peaceful trawler in the mist brings out every pair of glasses in the two cabins.

And now, where are those convoys? We are right in the midst of the danger field. On this spot, the Punxatawney was sunk with all hands, and over there the City of Shoreditch was struck down. Where are the convoys? Ask the winds that far away disperse the streams of hot air. One loyal Englishman hopefully suggests that they may be so far ahead of us that we can’t see them. And he’s right, inasmuch as they are at least 500 miles ahead, and somewhere in the North Sea.

The afternoon grinds away in this feverish fashion, the foggy evening descends; there isn’t any submarine, any visible convoy, any frowning battleship. We are not stopped, nor interfered with, nor observed, and so far as we can detect, if we were a German pirate we could sail right up the Mersey and shell Liverpool itself.

But when, with the lamps of the city ahead, the stewards turn on the deck lights and the boats are swung in again, you can tell what weight has been on the passengers’ minds by the cheer they raise– a cheer and more than one huge sigh of relief.

But, how about those convoys anyway? Why, there weren’t any. The British government didn’t provide them. The ship is one of the nation’s dearest possessions and cost a staggering sum, to which the government contributed, but the government didn’t provide any guard for it, and it might have been sunk as easily as the Falaba, the Wayfarer, and the rest of the great fleet of recent merchantmen that now paves the Irish Sea.

When you are about to board a steamer for Liverpool and you read in the dispatches how all the waters thereabout are alive with submarines zealously sinking everything that floats, the news is not exhilarating. Here is an account of a steamer like yours torpedoed close by Liverpool lightship itself– the audacious undersea raider! It jolts you up a lot inside; there’s no use denying it.

The most of us would fain die a dry death, if any, and anyway, to be spilled in the middle of the night from a warm berth into the icy waters of the Irish Sea is no way to treat a man of peace. It gives you gooseflesh to think about it.

The gooseflesh idea and the weird terrors of the German submarine fleet struck home to a flock of passengers booked for the ship I sailed on. At the last moment, the thing was too much for them and they skipped ashore. It was a new, handsome ship under the British flag, and in the neutral-flagged vessel in which these cautious ones now took refuge was a marine antique seasoned with the odors of a thousand voyages.

There was a howling old northeasterly gale, and the other ship must have navigated alternately on either end all the way across, but the actual afflictions of bilge water and tilting decks seemed to these people less than the pictures their imaginations painted of a shipload of passengers dumped into the sea while a submarine crew should watch them drown. There’s no accounting for taste.

For the honor of plain folk, I point out that all of the band that developed cold feet on this occasion were members of our highest circles and with names familiar to the financial and society reporters. This, to a group of English friends that apparently without profit had traveled among us, seemed to be a fact of great moment. One of them dwelt much upon it in the smoking room, and said learnedly: “Now, if your upper classes run away like this at the first sign of danger, you can’t have any hope for the rest of your people, you know. What would you do in a time of war?”

But, the cloud of international criticism lifted when a son of the West made answer. “Do?” says he. “Do what she has always done. Make leaders out of tanners, rail splitters, teamsters, farmer’s boys, or anyone else that is fit, and leave what you mean by the upper classes to grab off the fat contracts and sell rotten ships and eat to the government, as they always have. The kind of people that count in war time aren’t running away so you could notice it.” There is almost always a good hardy variety of patriotism in a transatlantic smoking room.

Still, I shall always maintain that goose flesh is only in good form when roasted and brought to the table with apple sauce. It has no proper business to come bothering around when you lie in your berth and count up how many steamers have been torpedoed in St. George’s channel towards which you are now flying. So, to cheer us up, they circulated that story about the convoy of British warships (which never came) to see us across.

But, everything has an end, and finally the great Lusitania tied up at the dock in Liverpool. We are going down the gangway from the steamer to the landing stage. But, who are all these clean shaven, furtive looking men that go snooping about, plainly watching the passengers?

Scotland Yard detectives, no less; a whole drove of them; and the business of landing is drawn out five hours, that they may scrutinize everybody. They pick out six of our passengers and have them detained by the police, being under the impression–O wise detectives!– that these are bloody-minded spies. One is a decent looking matron of Holland. She goes with the rest. The spy mania! Because of the war, it is epidemic in England now, and anybody that wears well fitting clothes and doesn’t chant his speech is liable to arrest.

Anyway, he is certain to be followed. Among our passengers was a little band of the most obvious typical tourists you ever saw, utterly harmless, and one of he Scotland Yard sleuths shadowed them about the pier and over to Birkenhead, peered into their compartment on the train, and dogged them half over a zig-zag tour of England’s show cities under the belief that they meditated mischief against the king. But when the spy mania comes in, of course all reason goes out.

Among the passengers on the Lusitania’s final completed eastbound crossing was Joseph Gallagher, of Lima, Ohio. He composed the following account of his voyage after the disaster:

Survivors’ statements that the passengers of the Lusitania were chatting and joking light heartedly up until the last moment on the submarines and torpedoes may strike the average reader as exaggerated. But by one who has sailed in the big Cunarder in war time will easily understand the confidence that her size and speed gave those on board.

I was one of those who traveled by her on her last completed voyage from New York to Liverpool, and though as one can now see the danger from submarines must have been very real I can quite confidently say that there was not a passenger on board who took the danger seriously.

On that occasion she was detained in New York nearly 24 hours by an unusually violent blizzard, and it is true that a couple of passengers, both American, alarmed by the talk about submarines in the smoking room, cancelled their passages and crossed by the American liner St. Paul. On the last night of the voyage, again, when we were tearing up St. George’s Channel at top speed a few nervous women refused to sleep in their cabins and spent an uncomfortable night on sofas and cushions in the saloon.

With the exception of these isolated instances, however, there was as much joking and laughter on the subject of submarines as though they were nothing more than phantom “Flying Dutchmen” and it was quite a common jest, if we saw a fellow passenger gazing dreamily at the sea, to ask him if he had “spotted a periscope” yet.

On the other hand, the official precautions that were actually taken against attack were very thorough. All through the voyage the ship was darkened at night, and when the Irish coast was neared, it was evident that Captain Turner, at least, had no illusions about the possibility of being torpedoed.

Every boat was swung out, ready to be launched at a moment’s notice, deck lights were extinguished altogether, and the saloon lights were put out at an unusually early hour. Passengers, too, were requested to remain “indoors.”

Right from New York the ship had been steaming at a comparatively slow pace, considering her real speed, ‘til we got near Ireland- indeed, we had never done 500 miles on any one day- but on the Friday before reaching Liverpool it was obvious to all of us that she was going full steam ahead for the last lap.

The increased vibration alone was enough to show the veriest landlubber that the race for safety had begun. And at noon the next day there was quite a little crowd round the log-board to see if the ship had done anything in the way of breaking record. To everybody’s intense surprise the log showed only 450 miles; figures, if anything, slightly under the average daily run we had made from New York. The mystery was explained (unofficially) later on when we heard that the run was in actual mileage 580 miles, but that we had been “zig-zagging” out of our course for the express purpose of baffling any submarine that might be lying in wait for us. I cannot vouch for the truth of this statement but it is the only explanation that seems to fit the facts.

Another singular incident occurred on the same night. In spite of the warning to passengers to avoid the decks, one of the steerage passengers persisted in remaining on the lower deck. Presently he began striking matches with the apparent object of lighting his pipe. This he found a strangely difficult proceeding. Match after match was struck, flared up with uncommon brilliance in the intense darkness and then went out. His curious proceedings were not left unmarked, and before long one of the detectives on board- and there were few of us who even suspected the presence of these unobtrusive officials- went up to him, took him by the arm and led him away.

Whether, as the detective suspected, he was actually trying to signal the liner’s whereabouts to some German pirate, or whether he was merely a fool who did not realize the criminality of his act I cannot say. But he was certainly locked up for the night and kept under close supervision until we reached Liverpool. Of his ultimate fate, I know nothing. He was not, by the way, the only suspect on board. At least three other individuals were detained at the landing stage as suspicious persons but here again I know nothing of how they fared eventually.

I have quoted these incidents to show, light hearted as the passengers were the Cunard company were fully alive to the submarine peril and took every precaution against the danger that common sense could suggest.

There was one precaution I think no one neglected to take, little though he may have thought of the danger. And that was to see that the lifebelts in his cabin were handy and to make sure, by experiment, that he could slip one on easily at a moment’s notice. But, as I say, the dominant note that remains in my mind of the behavior of the whole ship’s company on the Lusitania’s last completed homeward trip was an unfailing lighthearted cheerfulness. Indeed, I should not be overstating the case in asserting that the precautions taken against submarine attack, so far from frightening the passengers actually added a pleasant touch of excitement and zest to the voyage.

It must be remembered, too, that nobody supposed for a moment that even a German submarine would attack without warning or that ample time would not be given all on board to escape. So that at the worst all we anticipated was a few hours in an open boat and plenty to talk about for the rest of our lives.

Mrs. C.S. Joshua Arrives in Wales

Reverend C.S. Joshua today received a letter from his wife in which she tells of her voyage across the ocean to Liverpool, England. The letter states that Mrs. Joshua and daughter, Ruth, are enjoying the best of health and are now located at Caerthilly, where they will remain during their stay in Wales.

In the letter it is stated that the voyage was most pleasant and uneventful. No German submarine bothered the Lusitania, on which she traveled, and the ship was convoyed hundreds of miles by warships. The ship arrived in Liverpool on April 10, but all passengers were held in the ship until the following day.

New Castle PA News, April 26, 1915.

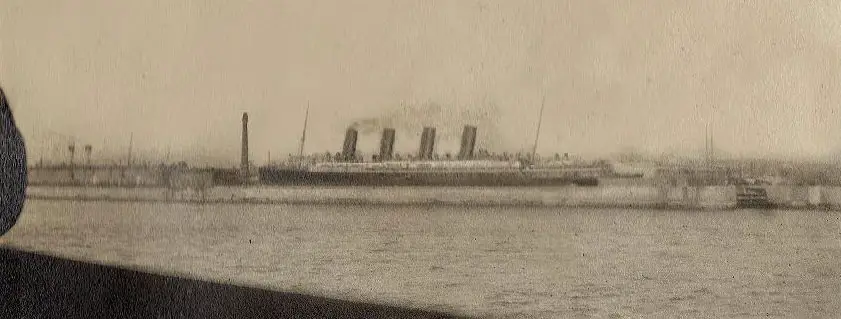

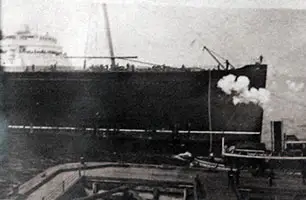

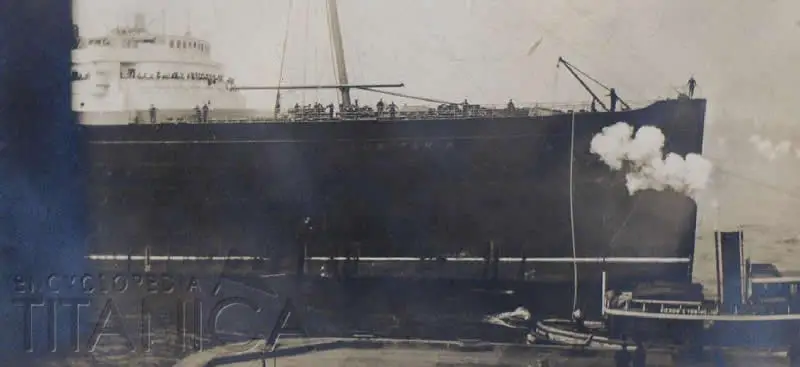

The press coverage of the final completed crossing was minimal, and mostly centered on Marconi. The best record of the voyage is a scrapbook of onboard and pier photos kept by an English family who traveled second class.

George Chalk, 47, a dentist from Richmond, his wife Esther, and children Hilda and Harvey, were on “New York holiday” and were visiting a friend who lived on West 73rd Street in Manhattan. His relations to fellow travelers, tailor Maurice Chalk, 32, and his wife, Zarah, 21, is not known. Maurice and Zarah were on their way to join his brother, B. Chalk, at 2817 Broadway. All six Chalks appear in various combinations in the deck snapshots.

The album shows all aspects of the voyage, which appears to have been a happy one, and includes a series of photos taken of the Lusitania as she came up river and docked. The source of these photos may have been either Max or Pauline Chalk, who had arrived with their seven children aboard the neutral St. Paul, on April 19, 1915, and who were staying with B. Chalk of 2817 Broadway.

The final arrival, April 17 1915

Album courtesy of Mike Poirier

Jean Timmermeister, Lusitania descendant and researcher, provided us with this excellent account of the April 17-24 crossing, left by a group of men who traveled from Liverpool to Butte, Montana.

Five Butte men who were on the Lusitania on the last voyage from Liverpool to New York have related how the Germans had attempted to torpedo the liner on that trip. The men who took that trip on the Lusitania are Frank Butler, an importer, with headquarters on the coast, who was at the Leggat yesterday; Owen Crowley, a relative of John J. Crowley of Crowley and Lockhart; Dennis O’Sullivan, Pat Driscoll, a relative of Dennis Driscoll, and Tom O’Brion, aged 16, a son of Tom O’Brion; a former shift boss at the Modoc mine. Each man said the trip across the Atlantic was made amid many perils, and that the passengers, almost to a person, were afraid that the Germans would attempt to send the liner to the bottom.

That a German submarine attempted to torpedo the ship while it was in St. George’s Channel, between Liverpool and Queenstown, was the statement of Mr. Butler, and his story is confirmed by that told by O’Sullivan, Driscoll, Crowley and O’Brion. In Liverpool the feeling was strong that the Germans would attack the ship, and there were some reservations canceled just before the gangplank was pulled up.

“We were told that the vessel would sail from Liverpool at 2 p.m., but we did not move, although everything was ready and every stoker was at work” said Butler. “The Admiralty had an airship over the ship to locate any submarine which might be waiting to attack her. It was decided to make the race through the channel after dark, and at 9 o’clock that night we got underway. After we had gone some distance, the ship stopped. We were told later that a submarine had been reported down the channel. The airship had signaled to the vessel to stop. Later, every pound of steam was put on and we raced down the channel at the Lusitania’s best speed. The submarine took up the chase at a point near Arklow, where the channel is narrow. If the Lusitania had not outdistanced the submarine, she would have been sent to the bottom. The passengers knew that something unusual was going on. Some of them wanted the captain to hoist the American flag, but he did not do so. The next day a notice was posted that submarine had followed the Lusitania 50 miles and had been outdistanced. Just before the Lusitania started to race through the channel, every porthole was covered and every deck light extinguished. There was no mirth aboard the big vessel, although the crew tried to us that there was no danger.”

O’Brion said that many of the passengers were on deck and that frequently some frightened woman would announce that she had seen the periscope of a submarine.“If that ship had been torpedoed when we were racing down the Irish coast, not all of us would have been saved” said O’Brion. “It did not seem as if there were enough boats for all the passengers and it would have been the third class passengers who would have had to take the chances.”

O’Sullivan said many of the first class passengers felt no fear that the vessel would sink, although many expected she might be hit by a torpedo. In London, many of the passengers had been told that the ship was so excellently built that she would stand the shock of a torpedo, and that watertight compartments would keep her afloat until all the passengers were taken off.

The passengers were agreeable to all the precautions taken to keep the movement of the boat a secret. It was not until Wednesday, four days after leaving Liverpool, that any lights showed. In the smoking rooms blankets were placed back of the lamps to prevent any light filtering through. The third class passengers were ordered below each night at 9 o’clock. The fare was increased about $5 because of the war risk.

O’Sullivan said that he went all over the ship to see if she had mounted any guns, as he had heard that the Lusitania carried some six inch guns. “There was not one gun aboard as far as we could find out, and certainly none were mounted. We were told that the vessel was not carrying munitions of war and that it was simply in the passenger business” said O’Sullivan.

Shipbuilder Albert Lloyd Hopkins, of Newport News, Virginia, went to visit his ailing father in Glen Falls, New York, during the final week of April, 1915. He assured his father that he would be alright, and that he would return in a month. The elderly Mr. Hopkins learned of the German warning, on May 1st, and became very distressed. The sickly man declined dramatically, and died within two days. His family in Glen Falls wrote to relatives in Virginia, telling about his final days and blaming his great worry over the torpedo danger for his death.

Hopkins’ body was recovered, and returned to the United States. He was buried in Glen Falls, New York.