Lest We Forget : Henry Sonneborn

“…he never spoke of the relationship in a negative way or acted like some family secret needed to be protected. ”

Schwabacher seems to have possessed considerable property. The substantial provision made by his will for his friend, Sonneborn, suggests a possible source of income to the latter, supplementing that from his own slender estate and enabling him, in middle age, to embark on the cultivation of his voice in Paris.

|

| Henry B. Sonneborn |

So spoke Umpire Edwin B. Parker, of the U.S. Mixed Claims Commission, on January 7, 1925. With these words, he posthumously doomed Lusitania victim Henry B. Sonneborn, of Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A. to an eternity of being an “inside reference,” for want of a better term, among researchers who have read through the Mixed Claims Commission Lusitania Case Summaries. Two men traveling together, who were “fast friends” enough to have named one another sole beneficiaries in their respective wills, who arranged to be buried together in the same mausoleum, and one of whom the court stopped just short of calling a “kept man” in its final judgment of the case seems, on the surface, to be one of the more scandalous affairs exposed by the disaster.

When we composed the segment profiling Mr. Sonneborn and Mr.Leo Schwabacher for Lest We Forget part one drawing heavily from newspaper articles contemporary to the disaster and hearings, and the case summary, it was with Parker’s rather snide dismissal of Mr. Sonneborn that we chose to conclude their portion of the story. So, when I was contacted by Mark Praetorius, the great -grandson of Henry Sonneborn’s sister Mary, who had read the article, I was initially unsure of how my reception would be. The family, after all, may well have viewed this as a skeleton, buried since 1925, being dragged out in a public forum, or as one more piece of character assassination directed at a man dead since May 1915. Mr. Praetorius; however, was interested in discussing the story, sharing what he knew from relatives old enough to have known Henry Sonneborn and from family papers, and hearing what my writing partner, Mike Poirier, and I knew about Leo and Henry from our research. As I correlated the information I already had with that supplied by Mark, and dug a bit deeper into Henry Sonneborn’s history through public records, I came to the conclusion that 99% of the story as it is commonly told is either inaccurate or flat-out wrong, that I had helped perpetuate a rather nasty fallacy, and that a belated apology is owed.

Henry Becker Sonneborn was born in Baltimore, Maryland, to Philip and Wilhelmina Becker Sonneborn, on October 14, 1872. The Sonneborn family ran a tavern on Light Street in downtown Baltimore and lived in rooms above it. He was a graduate of Baltimore City College, and along with his brother, Louis, half owner of a successful coal distributing company.

Wilhelmina and Philip Sonneborn

Mark Praetorius Collection

Leo ‘Lee’ Schwabacher was the son of Henry and Virginia Schwabacher, born on January 14, 1873, in Peoria, Illinois. The Schwabacher family made their fortune as liquor merchants, and were more than comfortably well off. The details of how Lee moved from the multi-servant family estate on Perry Avenue, Peoria, to Baltimore have not survived, but as of 1900 he was working as Louis and Henry Sonneborn’s bookkeeper, and boarding in a room over Philip and Wilhemina’s tavern.

After the death of Philip Sonneborn, in 1903, Wilhelmina and her family moved from Light Street to a larger and far more elegant house at 896 Battery Avenue, and bookkeeper Lee Schwabacher moved with them, still being referred to as their ‘boarder’. Simultaneous to the Sonneborn family’s move, Henry Schwabacher died, leaving each of his children a share of his estate large enough to generate $10,000.00 per year income, through interest. Beginning in 1906, Henry B. Sonneborn and Lee Schwabacher commenced traveling together, and after 1910 Henry sold his share of the coal business. The two men moved to Paris, France, with one another in 1911 allegedly to allow Henry to pursue a singing career. In October 1914, they returned to Baltimore for an extended visit prompted, in part, by unease over the escalating war in Europe. By 1914, Wilhemina Sonneborn was living in a Queen Anne style row house at 2209 Brookfliedl Avenue, where the two men stayed for the duration of their visit. Before their return to Paris in May 1915, Lee Schwabacher purchased a mausoleum in which they would one day be entombed together, and both men altered their wills naming the other sole beneficiary. Wilhemina Sonneborn traveled to New York City and boarded the Lusitania to make a last minute effort to persuade her son to cancel his passage. His response, along the lines of “A submarine? Don’t worry- we’ll send a telegram when we arrive safely” was quoted on both May 2nd, after the ship had sailed with Mr. Sonneborn and Mr. Schwabacher aboard, and again on May 8th after they died together.

I can remember my grandfather, Herman Praetorius, talking about, “Uncle Henry and Leo” and their frequent travels between the United States and Europe. The family was devastated by the loss of a loved family member and his friend at such a young age. The fact that Henry and Leo were of German ancestry and then to be killed by Germans was very upsetting to the family. Henry’s mother was Wilhelmina Becker Sonneborn(my great-great grandmother) and his father was Louis Sonneborn. I think that Wilhelmina was originally from Hanover, Germany. The Sonneborns had moved from Washington DC to Baltimore. They owned a Cafe’ on Light Street. It was always my understanding that Leo Schwabacher had moved to Baltimore from Peoria, Illinois and that he was considered family by the Sonneborns. As far as I know, Henry Sonneborn was never married. I had the impression that the family was comfortable with their relationship. I guess folks did not question things like they do today.

The 896 Battery Avenue residence was within an easy 3 block walking distance to 629 Light St. The Tavern was on the east side of the street. The block was razed to make room for the Maryland Science Center and grounds that now fill the entire east side of the block. I remember grandfather Herman talking about going to the tavern as a boy. I do not know how long the Sonneborn Cafe was in operation or if Henry ever worked there at any time in his life.

The house at 2209 Brookfield Avenue is still there. The neighborhood is called Reservoir Hill, as it is situated just below Druid Hill Park and Druid Lake. It is a large three story brick townhouse, being 18 feet wide and approximately 3000 sq. ft. Sadly, that neighborhood is very run down, but in 1915 it was very affluent. I am pretty sure the photo I sent to you of Henry with my grandfather was taken in Druid Hill Park. It would have been a short walk from the house. The park is still very pretty, today and the lake is still a water supply for the city.

~Mark Praetorius, December 2005.

TRAVELLING COMPANIONS

Henry and Lee’s first known trip together was a European jaunt during the first half of 1906. They boarded the Kaiserin Auguste Victoria at Dover, England, and were processed through Ellis Island on July 14th. They disembarked with one another, and were listed sequentially on the manifest. Both men gave the age of 35 years, and each listed his occupation as “merchant.” Lee Schwabacher described himself as single, Henry Sonneborn answered “married.” In 1908 they traveled to Europe again aboard the Kronprinz Wilhelm, and returned via Cherbourg on the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, arriving in New York on September 15th. In 1911, after a time apparently spent in Paris, they returned to the United States aboard the Lusitania. When they, figuratively, passed through Ellis Island on October 13th, both men declared themselves as being married, and their destination Wilhelmina Sonneborn’s new Queen Anne style row house on Brookfield Avenue, Baltimore. A November 1913 visit, commencing with a voyage aboard the France, saw both men describing themselves as single. Their final arrival, on October 9, 1914, was aboard the Lusitania and, again, both men declared themselves unmarried. These are the known voyages the men made together, and it is interesting to note the several occasions on which one, or both, of the men claimed to be married when entering the country ~ perhaps to divert suspicion about the nature of their relationship.

“LOVE UNCLE HENRY AND LEE”

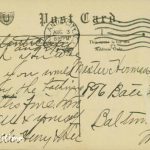

With the exception of the family photographs, the single greatest surviving link to Henry Sonneborn and Lee Schwabacher is a collection of 29 postcards they mailed from various points in Europe, and from New York City, to Henry Sonneborn’s nephew Herman Praetorius. Through the generosity of Mark Praetorius, we present the collection in its entirety.

Did Herman Praetorius ever speak of the impact of the disaster? Only that it was a very sad and difficult time for the family, especially for his grandmother, Wilhelmina. Honestly though, Grandfather Herman talked more about the years of Uncle Henry’s travels more than the tragedy of his untimely death. Herman was close to his mother’s side of the family as he lived with them and he was an only child. I have a feeling that Herman was sort of a surrogate son for Henry. German families did tend to be very tight the first and second generation in this country. It is not like that today. Did he ever talk about the impact on him? What he was doing when he heard the news? I know he was only 20 years old at the time. That is probably about the same time he joined the Navy. I was 18 when grandfather Herman died and not as interested in family history as I am today. I certainly would ask more questions if Herman was sitting in front of me.

The main thing I remember is that Herman spoke of Henry’s love of travel, and how much he(Herman) enjoyed receiving the many post cards from Europe as a young boy. Herman spoke little of his other uncles and aunts, so it appears the worldly Henry left an impression. I do not recall if Herman ever said if Henry was a serious or funny person. I assume he had some of both, as most of us do. The post card messages seem to show someone with a love of family, and not too pretentious.

I do think that the postcards are a very nice testament to Henry and Leo’s lives and their relationship. It is obvious to me that they enjoyed culture, travel, and the finer things in life and it was nice that they could share this. I am sure it was not easy to find and maintain a gay relationship in the early 20th century. Obviously they were fond of each other and Henry shared Leo with his family. I guess the difference in monetary assists makes it appear that Henry could have been a “kept man“, but somehow, I don’t think it was that way at all. I think it was a mutual appreciation of culture, music and traveling compatibility that made the relationship work and last until their untimely deaths. I am just glad that my grandfather kept all the postcards, always signed, “Uncle Henry and Lee”. We have something to remind us that they were living, breathing and loving people, not just victims of a now distant tragedy.

~Mark Praetorius, December 2005/ August 2006.

Notice that at least one of the cards, postmarked August 30th 1908, and September 8th 1908, showing Interlaken and the Jungfrau, was written by Leo Schwabacher.

“KEPT MAN”

The most damaging part of Parker’s summary was the declaration that Henry Sonneborn was a man of slender estate, unemployed, and seemingly being supported by Leo Schwabacher. “The inferences from the meager statements contained in the record are that the resources of decedent were slender and his income small. The property of his estate, both real and personal, inventoried only $13,107.653.” One wonders what criteria Umpire Parker was using to judge “slender.” Sonneborn’s yearly income, prior to the sale of his share of the coal business was listed as $8,400.00, a more than adequate amount upon which to survive ca 1910, and only $1600.00 per year less than Mr. Schwabacher was earning in interest on his inheritance. $13,100.00 was one of the larger estates left by any of the American victims. Mr. Sonneborn’s lost personal effects were valued at $2,230.50. It may be noted that Allan Loney, socially well connected Lusitania victim and father of noted survivor Virginia Bruce Loney, was described in the record as having the earning potential of $10,000.00 per year as a broker and bond salesman, of having lost $1235.00 worth of personal property in the disaster and “…died intestate…his daughter inherited his entire estate which does not appear to have been large.” without any additional editorial comment being made by the commission. Likewise, the fact that Charles Williamson not only died broke but also owed a large sum of money to some of the most socially correct residents of New York City was allowed to pass unnoted, as was the fact that he was traveling with a woman to whom he was not married. It would seem that Mr. Parker was basing his evident disapproval of Mr. Sonneborn on something other than dollar figures, because by 1925 standards, no less than those of 1915, Henry was far from poor. From the financial data presented in the case summaries, it is apparent that the two friends were more or less on equal footing, and ‘though there is no known surviving evidence of who paid for what, other than Mr. Schwabacher buying their shared mausoleum, it is obvious that this was not a case of an opportunistic poor man bleeding a well off friend.

“SINGING CAREER”

Jim wrote: I’m intrigued by the singing career Perhaps Henry sang semi-professionally around Baltimore? Did he sing “pop” or “classic” material? Were there any reviews and, if so, were they positive?

This is one area that I cannot give you any family history. Oddly, I do not recall Grandfather Herman every talking about Uncle Henry’s singing career, either in Baltimore or Paris. I am sure I would have remembered that.

~Mark Praetorius, August 2006.

Surviving evidence that Lee Schwabacher was bankrolling vocal training towards a Parisian singing career for Henry Sonneborn is slender. A post war newspaper capsule biography alluded to it, and the Schwabacher family apparently introduced that claim in court, but aside from that there is not a known shred of evidence to back the story up. Here is a theory we have tossed around as one possible explanation; The Schwabacher family were, evidently, not close to Lee. They swore in court, for instance, that he had moved to Baltimore in 1911 when, in fact, he had resided with the Sonneborn family since at least 1900. Henry Sonneborn’s younger brother, Philip, was an aspiring actor who lived in New York City. Henry and Lee visited with him several times and, in fact, were staying with him in the days leading up to their final departure. It is possible, if not likely, that one or both men might have given financial aid to the struggling artist, and that by 1925 word of that had gotten to the Schwabacher family in mutated form. A second, but less likely explanation, is that the newspaper capsule bio confused 40-ish Baltimore bachelor Sonneborn with 40-ish Baltimore bachelor Charles Harwood Knight, who also resided in Paris and did ambitiously pursue a career as a classical pianist, and that the Schwabachers were unknowingly relating details of Mr. Knight’s life rather than Mr. Sonneborn’s.

THE “WERE THEY OR WEREN’T THEY?” ISSUE

![HIND Leo_2]](https://www.garemaritime.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/HIND-Leo_2-218x300.jpg)

Leo Schwabacher and Henry Sonneborn

Mark Praetorius Collection

As with Mr. Sonneborn’s singing career, there is no direct, iron clad, evidence that the men were anything other than friends. Mark Praetorius regrets that none of the men’s letters or personal writings that might have settled the question once and for all are now known to exist. That is hardly surprising~ in 1914/1915, even in the most tolerant cities, discretion was necessary and when the men closed up their Parisian flat in preparation for their planned 6 month visit to Maryland, anything of an “incriminating” nature would have been taken with them. Then, as now, servants were not above supplementing their income through blackmail, and to leave letters or diaries untended in a place where someone with ulterior motives could have searched them out at leisure and removed them, would have been almost suicidally negligent. Our guess is that if there ever was a paper trail, it now lays at the bottom of the Irish Sea in the ruins of the liner. The best that can be said is that the men were exceptionally close, had lived with one another for at least 15 years and traveled with one another for at least nine. Each named the other as his principal beneficiary and, had their bodies been recovered, they would have been entombed with one another by pre-arrangement.

Family viewpoint: I cannot say that grandfather Herman ever stated that he thought Uncle Henry was a homosexual and that Leo was his life partner, but he never spoke of the relationship in a negative way or acted like some family secret needed to be protected. After all, he saved all of the postcard that Uncle Henry and Leo had sent to him during their many trips abroad. I also got the impression that his mother, Mary S. Praetorius and his grandmother, Wilhelmina Sonneborn were very fond of Henry, and that his lifestyle would not have changed that.

Leo was referred to as Uncle Henry’s “business partner” and “friend“. Also that he liked very much to travel. Never any mention of him being married or having children, nor any mention of his family.

Leo Schwabacher

Mark Praetorius Collection.My grandfather’s cousin, Anna Marie Franke said, at a family gathering when I was about 11 years old, that she remembered the “beautiful china” that Henry and Leo were taking back to Paris. I do not know if this was old family china, or china that they purchased new in Baltimore. I would think if they wanted to purchase new china, they would have waited until they returned to Europe.

I also feel certain the Henry and Leo were more than just friends and traveling companions. I am just glad that they managed to have a fulfilling ‘gay’ relationship in those times. I guess that is why they decided to live in Paris, as I know that Paris of that time was very arty and bohemian. I am sure being gay was just not the issue there that it was back in the States. I wish I knew their Paris address, but I have no record of that in with all the old papers.

~Mark Praetorius, December 2005/August 2006.

MARRIED MEN

One of the hazy areas of the story of Mr. Sonneborn and Mr. Schwabacher, is the question of whether or not either man was ever married. Both, at various times, claimed to have been and yet, at the Mixed Claims Commission Hearings, their families testified that neither had ever been wed. According to Mark Praetorius, no mention was made within the Sonneborn family of Henry being anything other than a bachelor. However, rather intriguing to note, in 1900, a Leo Schwabacher born in 1872 in Peoria, Illinois, was listed as living in Brooklyn with his wife, Silene. The Leo Schwabacher appears in the 1900 census as being a border at the Sonneborn’s Light Street residence in Baltimore, so either his marriage dissolved and he moved south at some point in 1900, or there were two men with the same name, of about the same age, and from the same home town living on the East Coast at that point: perhaps cousins?

THE SONNEBORN FAMILY AND THE DISASTER

Jim Kalafus Collection

When the Lusitania sailed on May 1, 1915, Henry and Lee vanished from the record . Their bodies were never recovered, and as of yet no account by anyone who knew them has surfaced to fill out the details of their final days. George Kessler later wrote of two men, rumored to be “German spies” who kept to themselves: one can make the case that this was Mr. Sonneborn and Mr. Schwabacher and, if so, that their final week might have been less than pleasant. Mark Praetorius has speculated on what his ancestors’ reaction, short term and long term, to the loss of both men must have been. The family was proudly German and to lose loved ones in an act widely condemned by anti-German forces everywhere must have led to a number of conflicting emotions. A 1915 news clipping from the Praetorius collection is an interesting “window” to how the Sonneborns may have felt:

|

For a year Mrs. Sonneborn’s health has been gradually failing, and her sons and daughters are now experiencing the added anxiety of shielding her s much as possible from the shock of news of the ship’s disaster although the bare fact has not been kept from her. Mrs. Sonneborn, in spite of her anxiety, is bearing no resentment towards the German torpedo boat that brought disaster to the Lusitania. She was born in Wiesbaden, Germany, nearly 80 years ago and lived there with her father when he was a professor at the university until she was 20 years old. Before her marriage, she was Miss Becker. She believes that Germany has given sufficient warning to all prospective travelers on this side of the ocean of the risk they were running to place the responsibility entirely on their shoulders when disaster occurs. This opinion is also shared by Mr. Sonneborn’s sister, Mrs. Philip Praetorius who, with her husband and children, makes her home with her mother. Their German blood makes it impossible for them to forget that the Lusitania is an English liner. |

Perhaps the article offers true insight into Mrs. Sonneborn’s mindset two days after the death of her son and a man she reportedly viewed as a “second son,” but one wonders how, if she was being kept in seclusion and denied news of the disaster, she managed to form so definite an opinion and how she managed to articulate it to a reporter. One also wonders if, in the first stages of shock at losing their family member and friend, any Sonneborn family member, no matter how proudly German, would voice a “blame the victim” sentiment to the press. Another odd detail is that Mrs. Sonneborn, described as being “in decline” had managed to travel to NYC on May 1st to plead with her son not to board the ship, as reported on May 2nd. Neither Mrs. Sonneborn nor her son were anything approaching celebrities, which vouches for the veracity of that particular story: the press would have had no reason to report it before the disaster had it not actually occurred. My interpretation is that no matter how pro-German Wilhelmina was, she was also afraid of what Germany might do, and made a last minute attempt to keep the two men off the ship. Would an ailing woman, who made a long train trip in an unsuccessful attempt to save the life of her son and his traveling companion be inclined to let the world know that they had brought their own deaths upon themselves, just 9 days later?

Herman Praetorius, the nephew with whom Henry Sonneborn kept in frequent contact via postcard.

Mark Praetorius Collection

Another telling factor is that Herman Praetorius, Henry’s beloved nephew, joined the US Navy, and Philip Praetorius, draftsman, spent World War One working on dazzle paint schemes for US Ships, a position he most certainly would not have been given had he been as pro-German as the clipping makes him appear to be.

Baltimore had a large German population in 1915, and one suspects that the article may have been ‘sweetened’ by a pro-German editor or reporter prior to publication.

Philip worked for A. Hoen & Company which was a very successful Baltimore lithographer. Philip would do the original watercolor or ink illustrations for advertising. I still have many examples of his original artwork. Technicians would transfer his designs to large lithography stones to be printed in volume. Philip also worked on dazzle paint designs for ships during World War I.

~ Mark Praetorius, July 2006.

A SECOND TRAVEL DISASTER

Mary Praetorius,

Mark Praetorius Collection

Two years after the Lusitania disaster, Wilhelmina Sonneborn lost her daughter, Mary Sonneborn Praetorius, in what was described at the time as New England’s worst-ever trolley accident. Mary was summering in Connecticut, and was returning to her home in Madison aboard a local car, when it was rammed by a speeding express car , the conductor of which had fallen asleep at the throttle after a 16 hour work day. He missed a turn off signal, and crashed into the “local” coming up the single track. 19 people died at the scene, crushed to death when the cars telescoped, and several others died of injuries in the days immediately following the accident. Mary Praetorius was paralyzed from the chest down, and taken to the hospital at Guilford, Connecticut, where she endured for four months before dying of sepsis in December 1917.

|

ALL OF DEAD IDENTIFIED; DEATH TOTAL MAY BE ADDED TO Last Body That of Mrs. Minnie Harrison Allen of Clinton. Mrs. Praetorius May Not Live. Tribbals Boy and Miss Day in Serious Condition. Positive identification was made today to the last of 19 Branford wreck victims as Mrs. Minnie Harrison Allen, housekeeper for Charles Hurd of Clinton. Mrs. Mary Praetorius of Baltimore, Md., who was injured in the wreck was reported in a critical condition at a Guilford Sanitarium today and her recovery is not expected. Her chief injury is to the spine causing paralysis from the chest down. Philip Praetorius, who was accompanying her to North Madison to spend the summer, escaped with lesser injuries and is now at North Madison as is William Kaiser of Baltimore, who also was only slightly injured. (New Haven Register, Tuesday August 15th, 1917) |

The 1917 Trolley accident must have been devastating to Wilhelmina Sonneborn, my great-grandfather, Phillip and to grandfather Herman. I am not sure if Herman was still in the Navy at that time. He did not speak about the trolley accident a lot as I could tell it was a very sad memory for him. Mary Praetorius could not be moved to Baltimore and had to remain in Connecticut in a sanitarium. My great-grandfather had to go to Connecticut to visit her. She did not die until December from complications from her injuries sustained in the crash. Her death certificate states sepsis as the cause of death, but she was left paralyzed by her injuries. It is very sad, as she was only in her early 40s. I do not recall that there was any trial, or compensation from the Trolley company. Mary’s remains were brought back to Baltimore for interment at the Sonneborn plot in Loudon Park Cemetery. That plot has the remains of Wilhelmina and Philip Sonneborn, their son Karl and his infant son, Philip, Mary Sonneborn Praetorius and Philip E. Praetorius.

AFTER THE FACT:

Wilhelmina Sonneborn died in the early 1920s, as stated in the Mixed Claims Commission summary. As of 1930, Philip and Louis Sonneborn, her surviving sons, were running boarding house for unmarried gentlemen in Baltimore. Philip had never married, while Louis~ Henry Sonneborn’s former business partner~ was living apart from his wife. Philip listed himself as an “actor” and, oddly, both men were passing themselves off as being ten or so years younger than their actual ages, with Philip claiming 45 and Louis claiming 47. That year saw Philip Praetorius an inmate in a hospital where he had been sent following a massive stroke. Herman Praetorius, Henry’s beloved surrogate son, died in August 1972, and his son, Franklin, a year old when the court decision was handed down, died in 1991. Franklin’s son, Mark, remains as the family historian and , along with his sister, may be the final living descendents of the Sonneborn family.

It is nice to know that my ancestors were not dull

~Mark Praetorius, August 2006.

From Lest We Forget part 3, coming to Encyclopedia-Titanica in early 2007.

![Mark_Praetorius_2[1]](https://www.garemaritime.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Mark_Praetorius_21-150x150.jpg) DEDICATIONS: This article would not have been possible without the generosity and input of Mark Praetorius, to whom it is gratefully dedicated. Thanks, Mark, for enabling me to “do a 180” from my original rather sensationalistic view of the story, and turn it into something quite respectful!

DEDICATIONS: This article would not have been possible without the generosity and input of Mark Praetorius, to whom it is gratefully dedicated. Thanks, Mark, for enabling me to “do a 180” from my original rather sensationalistic view of the story, and turn it into something quite respectful!

Thanks as well to Tim, and Mike, and Marty, who’ve listened to me discussing this project since last January, and to Harald Advokaat and Brian Hawley for a lot of good advise.

And, I’d be remiss if I did not give a special nod and dedication to Lesley Veile, my “gal” at the office of Gare Maritime US. In addition to typing out the archival material for this article and the Vestris piece, she has been a great sounding board for ideas ~ some successful, others which died a-bornin.’ She also makes sure that the office is kept spotless (on her own time, not mine, of course) the coffee fresh, snacks on hand, and the Men’s Room sanitary. She does not object when I tell her to go out and ‘buy something attractive’ for my special someone who ‘is just about your size~ so use your own judgment’ and is always willing to be flirtatious~ but never cheap ~with my male clients. Having now covered all 6 “Thou Shall Nots” on the list of things recommended one never say to one’s data entry expert, I’ll wrap it up by giving a sincere “thank you.”

COMPLETE LIMITATION OF LIABILITY TRANSCRIPT

United States of America on behalf of Estate of Wilhelmina B. Sonneborn, Deceased, Mercantile Trust and Deposit Company of Baltimore, Maryland, Executor of the Estate of Henry B. Sonneborn, Deceased, Louis B. Sonneborn, Philip B. Sonneborn, Carrie Henrietta Schreiber, Herman H. Praetorius, and Estate of Mary Christine Praetorius, Deceased,

Claimants, v. Germany

Docket No. 2040

Parker, Umpire, rendered the decision of the Commission.

This case is before the Umpire for decision on a certificate of the the two National Commissioners certifying their disagreement.It appears from the record that Henry B. Sonneborn, an American national, a bachelor 44 years of age, was lost on the Lusitania. He left surviving him a mother, Wilhelmina B. Sonneborn, two brothers, Philip B. and Louis B. Sonneborn, and two sisters, Carrie Henrietta Schreiber and Mary Christine Praetorius, all American nationals. Some three years prior to his death he had retired from the coal business, which he had been pursuing in Baltimore and which it is alleged yielded him a return of $8,400 per annum, and since he had been residing in Paris engaged in cultivating his voice. The inferences from the meager statements contained in the record are that the resources of the decedent were slender and his income small. The property of his estate, both real and personal, inventoried only $13,107.53. He was traveling with his friend Leo M. Schwabacher, also a bachelor, who was also lost on the Lusitania (see Docket No. 2200).These two men seemed to have been fast friends and each named the other a legatee in his will. Provision is made in Schwabacher’s will for the burial of the two friends in the same mausoleum. The body of neither was recovered. Schwabacher seems to have possessed considerable property. The substantial provisions made by his will for his friend Sonneborn suggests a possible source of income to the latter, supplementing that from his own slender estate and enabling him, at middle age, to embark on the cultivation of his voice in Paris.

However this may be, the record fails to disclose that, with the exception of his sister Mrs. Praetorius and the members of her family, any of the claimants herein were dependent upon the decedent, Henry B. Sonneborn, or, measured by pecuniary standards, have sustained damages by reason of his death. His mother, who at the time of the sinking of the Lusitania was 75 years of age, has since died, but the record does not disclose the date of her death. It would seem, however, that she had an income of her own and left an estate of which her son Philip B. Sonneborn, one of the claimants herein, is administrator. His old mother was not mentioned in the will of the decedent, Henry B. Sonneborn, save that in bequeathing his jewelry, furniture, silver, books, rugs, and other similar personal effects to his friend Leo M. Schwabacher the testator provided that in the event his said friend should not survive him then this bequest should go to his mother. These effects so bequeathed to his mother were inventoried at $1,457.90. The decedent left one policy of life insurance, of $1,000, in which a nephew and a niece were named as beneficiaries. No inference can reasonably be drawn from the record other than that the aged mother of the decedent was not dependent upon him and that he did not contribute to her support

Mrs. Praetorius , a sister of the deceased, survived him. At the time of his death she was 47 years of age. In 1911 her husband had suffered an apoplectic stroke which had left him an incompetent. Thereafter Mrs. Praetorius with her invalid husband and minor son made her home with her old mother, Mrs. Wilhelmina Sonneborn, the decedent contributing $100 per month toward paying the household expenses of his mother’s establishment for the benefit of his sister, Mrs. Praetorius, her invalid husband, and her son. In his will the decedent left in trust the sum of $2,000 for his nephew, Herman H. Praetorius, the income therefrom to be paid him until he reached the age of 25 years, whereupon the principal should be paid him. Mrs. Praetorius died December 15, 1917.

The decedent had with him on the Lusitania personal effects, including jewelry, aggregating in value $2,230.50.

Applying the rules announced in the Lusitania Opinion and in the other decisions of this Commission to the facts as disclosed by the record herein, the Commission decrees that under the Treaty of Berlin of August 25, 1921, and in accordance with its terms the Government of Germany is obligated to pay to the Government of The United States on behalf of (1) Herman H. Praetorius the sum of two thousand five hundred dollars ($2,500.00) with interest thereon at the rate of five per cent per annum from November 1,1923, and (2) Mercantile Trust and Deposit Company of Baltimore, Maryland, Executor of the Estate of Henry B. Sonneborn, Deceased, the sum of two thousand two hundred thirty dollars fifty cents ($2,230.50) with interest thereon at the rate of five per cent per annum from May 7, 1915; and further decrees that the Government of Germany is not obligated to pay to the Government of the United States any amount on behalf of the other claimants herein.

Done at Washington January 7, 1925.

Edwin B. Parker, Umpire

United States of America on behalf of Louis H. Schwabacher, Jule K. Schwabacher, Hettie S. Reichman, Florence Messing, Mrs. Maud S. Weil, Mrs. Bertha S. Greisheim, The Mercantile Trust and Deposit Company of Baltimore, Maryland, Executor of the Estate of Leo M. Schwabacher, Deceased,

Claimants, v. Germany.

Docket No. 2200

Parker, Umpire, rendered the decision of the Commission.

This case is before the Umpire for decision on a certificate of the two National Commissioners certifying their disagreement.It appears from the record that Leo M. Schwabacher, an American national, was lost on the Lusitania. He was a bachelor whose age is given at several places in the record as 49, at several other places as 43, and in another as 44 years. He was traveling with his friend Henry B. Sonneborn, who was also lost in the Lusitania, (see Docket No. 2040). The decedent had taken up his residence in Baltimore in the year 1911, where he engaged in the coal and wood business, which, however, had been disposed of several years prior to the sinking of the Lusitania, and the inferences are the decedent was spending the greater part of his time in Paris with his friend Sonneborn.

The decedent had inherited a substantial amount from his father’s estate from which he derived an income of approximately $10,000 per annum. He was survived by an aged mother, since deceased, and several brothers and sisters, all of whom are claimants herein and possessed independent income. The decedent did not reside with or make any contributions to any of his relatives and there is nothing to the record to suggest that any of them were dependent upon him or could reasonably have anticipated contributions from him in the future. The will of the decedent made substantial provision for his friend Henry B. Sonneborn, who was lost with him, and the legacy intended for this friend reverted to his residuary estate, of which the individual claimants herein are the beneficiaries.

The claim is made that the decedent rendered valuable services to his brothers and sisters through his participation in the management of their father’s estate. The father, however, had in his will named a brother and a brother-in-law of the decedent as executors of his estate and the record indicated that it was actively managed by them, while for some time prior to his death the decedent spent much of his time in Europe. The damages, if any, suffered by the claimants herein because of their being deprived through his death of the intermittent service of the decedent in the management of their father’s estate are too remote to furnish any basis of recovery against Germany (see Decision in Life-Insurance Claims, Decisions and Opinion, pages 121-140). The record fails to disclose that any of the claimants herein have sustained any damages, measured by pecuniary standards, resulting from the death of the deceased.

The decedent had with him on the Lusitania personal property, including jewelry and cash, aggregating in the value $5,050.

Applying the rules announced in the Lusitania Opinion and in the other decisions of this Commission to the facts as disclosed by the record herein, the Commission decrees that under the Treaty of Berlin of August 25,1921, and in accordance with its terms the Government of Germany is obligated to pay to the Government of the United States on behalf of the Mercantile Trust and Deposit Company of Baltimore, Maryland, Executor of the Estate of Leo M. Schwabacher, the sum of five thousand fifty dollars ($5,050.00) with interest thereon at the rate of five per cent per annum from May 7, 1915; and further decrees that the Government of Germany is not obligated to pay the Government of the United States any amount on behalf of the other claimants herein.

Done at Washington January 7, 1925

Edwin B. Parker, Umpire.

![Sonneborn Marie S[1]. Praetorius](https://www.garemaritime.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Sonneborn-Marie-S1.-Praetorius-209x300.jpg)